Theseus is often referred to as the Athenian Herakles as his exploits are often patterened after those of the Panhellenic Herakles. However, like Perseus and Bellerophon, Theseus is independently associated with one major heroic achievement throughout the Greek world and relatively early in Greek history: slaying the Minotaur.

Left: Attic black-figure kylix (c. 530 BCE). MET 09.221.39.

Theseus, with the help of Ariadne, Minos' daughter, killed the monstrous Minotaur. The episode appears here with youths and maidens as spectators.

Although most of the heroes in Greek myth fit into the same heroic mold exemplified by Herakles,[1] none of the heroes seem to pattern their stories directly after those of Herakles to quite the same degree as Theseus.

Black-figure amphora attributed to Princeton Painter (c. 545-535 BCE).

Princeton University Art Museum. Trumbull-Prime Collection, y168

Theseus grasps the Minotaur by the horns and prepares to thrust his sword into the beast’s abdomen. Athenian youths who accompanied Theseus into the Labyrinth are shown on either side. Note that all the figures are beardless as they were notably youths sent as sacrifice to Crete.

Theseus was the local hero of Athens. We know that many tales and aspects of Herakles’ tales were originally those of local heroes from cities and towns throughout the Greek world whose identities were subsumed by, or amalgamated with, the figure known as Herakles.[2] Indeed, many kings throughout the historical Greek world claimed to be descendants of Herakles, and they could make such claims based on the conspicuously large number of aristocratic women Herakles bedded throughout the course of his adventures. That was one way in which various villages, cities, and towns found their way into the klea andrōn (tales of heroes). Theseus represents another method of connecting one’s local hero to the larger, more Panhellenic figure of Herakles. Rather than merge identities with the most famous hero in the Greek world, myths of the Athenian Theseus weave his deeds around those of Herakles and, in fact, copy them, sometimes in stark ways. Thus, Theseus can be viewed as the Athenian Herakles.

While many of the myths surrounding Theseus appear to be late additions to the canon or might seem like somewhat shameless attempts to associate the hero with Herakles, Theseus does have a signature exploit that he can claim all to himself: the slaying of the Minotaur. Like Perseus and Bellerophon, Theseus’ most popular heroic exploit is attested early in the surviving record, and its theme is similar: monster slaying. The slaying of the Minotaur represents the conquest of civilized Greek culture over the savage ferocity of nature and an unjust ruler that came before (Minos, Crete). Theseus’ other exploits, like those of Herakles and the other heroes, reinforce this theme as well.

While Herakles enjoyed both a mortal and immortal father, the hero’s actual descent was clear and generally agreed upon in the surviving sources. The same cannot be said of Theseus. Whether Theseus is the child of Poseidon or Aegeus depends on the iteration of the story. Regardless of his genetic heritage, it is generally Theseus’ relationship with his mortal father (Aegeus, king of Athens) that factors most directly in the majority of surviving myths that surround the hero. Nevertheless, his association with Poseidon does offer a more comforting rationale for the superhuman abilities featured in his labors. Apollodorus navigates this discrepancy with the throwaway line: “During the same night Poseidon also had intercourse with [Aithra, Theseus’ mother].”

Terracotta Campana relief (c. 100 BCE-100 CE).

British Museum 1893,0628.6

"Theseus, shown lifting a huge rock under which his father Aigeus, King of Athens had hidden the sword and sandals. Theseus' mother Aithra stands behind him, indicating the hiding spot."

© The Trustees of the British Museum(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The savage children of Poseidon are generally more popular than those heroes who claim descent from the sea god. The most famous of Poseidon’s monstrous progeny is Polyphemus, the savage cyclops whom Odysseus blinds in the Odyssey. Apollodorus also names Skeiron as a child of Poseidon whom Theseus kills on his trek to Athens.

Each of Theseus’ labors involve the hero slaying superhuman beings that pose a direct threat to human civilization. Thus, in slaying these monstrous foes, Theseus metes out justice while making the world safer for human habitation. The majority of these labors take place on Theseus’ trek up the Isthmus of Corinth, from Troezen to Athens. While all of the people/creatures that Theseus encounters are characterized as savage in some way, the most common form of savagery is that they violate the laws of xenia (hospitality, guest-friendship). The violation of xenia is a common marker of uncivilized figures or behavior in myth, and the best example of that amongst the persons Theseus encounters in Procrustes. T. H. Carpenter describes the episode:

Prokrustes (Apollodorus calls him Damastes or Polypemon) was the last of the evil-doers Theseus encountered on his way to Athens, and he is perhaps the most memorable of his adversaries. he had a bed (or bes) in his home near Eleusis and offered hospitality to passers-by. But when they lay on the bed, he adjusted their sizes to match the bed, lopping off pieces from those who were too long and hammering out those who were too short. As with the rest, Theseus killed him using the means the villain had used to murder others. [3]

Some of Herakles’ labors seemed more frivolous than others. For example, cleaning Augeus’ stables was a feat that emphasized Herakles’ physical and intellectual abilities, but the “monster” he defeated was not some existential threat to civilization but, rather, the demeaning task of shoveling shit, a chore that would be expected of a slave or lower class servant rather than a member of the aristocratic ruling class. By contrast, Theseus’ labors are more overtly focused on cleansing the land of threats to civilized human habitation and meting out justice to evil doers. Thus, every encounter Theseus has on his trek from Troezen to Athens overtly perpetuates the theme of bringing order or justice to brigands and thieves.

Attic red-figure kylix attributed to the Penthesilea Painter. (c. 475-425 BCE).

From left to right: Theseus wrestles with Kerkyon; Theseus raises his axe to make Procrustes “fit” his bed; Theseus bends back the branch of a pine tree that he will latch toPityocamptes (Sinis).

In all three encounters, Theseus punishes the evil-doers by visiting the same horrific fate on them that they forced upon innocent travelers who entered their haunts.

Photo: Egisto Sani

Copyright: (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Some of Theseus’ activities tie his adventures to those of Herakles in a more direct way. For example, The Cretan bull, which Herakles subdued and brought before Eurystheus at Mycenae, was subsequently released. The same bull later made its way to the plain of Marathon in Attica where Theseus, too, battled the beast and ultimately slew it, making the area safe for humans to exploit the rich plain again. Apollodorus tells us that “Theseus joined Herakles’ campaign against the Amazons and carried off Antiope, though others say Melanippe, and Simonides says Hippolyte.”[4] And in Herakles’ final labor, during his trip to the underworld to bring back the watchdog Kerberos, Herakles came across Theseus and Peirithoos, rescuing the former.

Photo credit: Egisto Sani.

Copyright: (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Attic red-figure kylix by the Kodrus Painter (c. 440-430 BCE).

The British Museum 1850,0302.3

The early labors of Theseus encircle the hero’s greatest accomplishment: the slaying of the Minotaur on Crete.

Each encounter is thematically linked with Theseus slaying a person or beast that represents an affront to justice or order in a civilized society.

Clockwise from the top: Theseus wrestles Kerkyon. Theseus cuts off the feet of Procrustes. Perseus hurles Skeiron off a cliff. Theseus wrestles the Cretan bull on the plain of Marathon. Theseus ties Pityocamtes to a pine tree. Theseus confronts Phaia and her monstrous sow.

When Theseus finally arrived at Athens, Apollodorus tells us that Medea had married his mortal father, Aegeus, and she saw Theseus as a threat to her position. Medea "plotted against [Theseus]. She persuaded Aigeus to be on guard, alledging that Theseus was plotting against him. Aigeus did not recognize his own son and in fear sent him against the Marathonian bull."[5] This tactic of a king who concocts a mission designed to kill the hero is a stock heroic template that occurs with Perseus’ pursuit of Medusa’s head, Bellerophon against the Chimaera and other minor achievements, most of Herakles’ labors for Eurystheus, and Jason’s quest for the golden fleece.

Medea plays only a small part in the story of Theseus, but she brings with her a vivid presence in the Greek mythological memory through her interactions with Jason and the Argonauts. In Medea’s interactions with Jason, she is portrayed in a particularly misogynistic manner as a kin-killing, barbarian female who rebels against the gender expectations of the patriarchal and “civilized” Greek society – similar to other female barbarians such as Amazons. When her scheme to kill Theseus via the proxy of the Cretan Bull fails, Medea resorts to other means, which Theseus manages to narrowly avoid:

Aigeus got a poison from Medeia that same day and gave it to him. When Theseus was about to drink the poison, he presented his sword to his father as a gift. When Aigeus recognized it, he knocked the cup from his hands. After being recognized by his father and learning of the plot against him, Theseus drove Medeia out of the country. [6]

As soon as Theseus establishes himself at Athens, he finds himself in position to accomplish the most famous of his youthful exploits, the Minotaur beneath the palace at Knossos.

Attic red-figure kalyx-krater attributed to a painter in the Group of Polygnotos (c. 440-430 BCE). Met 56.171.48

Theseus subdues the Bull of Marathon, the same Cretan Bull that Herakles brought back to the court of Eurystheus and then released. Note that Theseus also wields a club, a bit of iconography that makes differentiating between the two heroes and the scene in question more difficult. In the case of this krater, the position of the figures appears to be a copy of a similar scene on the south frieze of the Parthenon.

The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur is incredibly popular. It contains the regular themes of heroic exploits: Theseus slays the half-man, half-beast monster that represents a savage threat to civilization. This myth, however, is loaded with the weight of Aegean prehistory as well. Crete was the seat of power in the middle and parts of the late bronze age Aegean. The culture that dominated the Aegean at that time is referred to as Minoan by modern archaeologists. The Minoans were succeeded by a mainland culture referred to by modern scholars as Mycenaean. The Mycenaeans, we have verified, were early Greeks. Between roughly 1600-1400, the two cultures existed side-by-side, with the Minoans exerting dominance over the area. But sometime in the mid-to-late 15th century, the Mycenaeans came to dominate and (perhaps) subsume Minoan culture. The myth of the Minotaur seems to corroborate this view.

The myth tells of a time when the Cretans, ruled by king Minos, were the dominant power in the Aegean, and they exerted that power over the mainland, specifically the mainland kingdom of Athens, which was forced to send virginal boys and girls on the cusp of adulthood to Crete at the threat of all out war if Athens refused. These young Athenians were then locked in a labyrinth beneath the Palace of Minos at Knossos, where they were hunted down and eaten by the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull that was the product of the unnatural coupling of Minos’ wife (Pasiphae) and a white bull with whom Poseidon caused her to fall in love. Theseus’ victory over the Minotaur and subsequent victory over Minos and Crete mirrors the rise of the mainland Mycenaean civilizations over the earlier Minoan civilization.

Theseus’ victory over the Minotaur was not, however, an entirely positive one. Like many heroes, including Herakles, Jason, Odysseus, and Achilles, Theseus suffered and made mistakes. In Theseus’ case, he neglected to raise the proper color of sail on his voyage home, causing his father, Aegeus, to commit suicide in grief over the perceived death of his only son and heir to the throne of Athens.

Also, like Herakles and Jason, Theseus made use of foreign women, lovers whom the heroes would later abandon for one reason or another. In the case of Ariadne, she was abandoned before Theseus made it home from Crete, conveniently after her usefulness had come to an end. Herakles was driven mad by Hera, murdering his first wife and later planned to abandon Deianera for a younger Iole, had he not been accidentally poisoned by the former. Finally, Jason depended on the aide he received from the foreign princess Medea in his quest for the golden fleece, and he even married her and began a family, but when the opportunity presented itself for him to marry a Greek princess, he abandoned Medea. As a part of the conquest of the Amazons, Theseus returned home with an Amazon bride, Antiope, whom he eventually discarded for the Cretan princess, Phaedra. Compared to the actions of Herakles and Jason with regard to faithlessness, Theseus’ action may be viewed as mild, but they fall into a fairly consistent pattern in Greek myth regarding the status of females vis-a-vis male heroes as well as the cultural assumptions about the status of foreign (barbarian) vs. Greek peoples – to be female is to be less than male just as to be non-Greek (i.e., a barbarian) is to be less than Greek.

One of Theseus' more famous exploits during his tenure as king of Athens was joining with Herakles on the latter's labor to retrieve the war belt of Ares that the god had given to the Amazon queen Hippolyte. This is generally referred to as the Amazonomachy. Antiope was one of Hippolyte's sisters who was either captured or fell in love with Theseus (ala Ariadne). In any case, Theseus brought Antiope back to Athens with him and made her his wife. He would later put her aside in order to marry the Cretan princess Phaedre. Whether to win back their stolen princess (Antiope) or to punish Theseus for setting Antiope aside in order to marry Phaedre, the Amazons attacked Athens under the leadership of Penthesilia (another sister of Antiope and Hippolyte). Theseus, Peirithoos, and the Athenians drove off the Amazons in this second Amazonomachy, usually referred to as the Attic War.

Attic red-figure volute-krater attributed to the Karkinos Painter (c. 500 BCE).

Met 59.11.29

Theseus is depicted carrying away Antiope (identifiable by the Phrygian cap) toward a waiting chariot, probably driven by Peirithoös, as he is pursued by an Amazon on horseback and another on foot.

The aftermath of the Minotaur episode resulted in one of the most recognizable allegories from Greek myth: Daedalus and Icarus. The metaphor of this story is common in Greek myth, and we will run into it below when we cover Theseus' and Peirithoos' ill-conceived scheme to marry into the family of Zeus.

Daedalus was the master architect who built the cow contraption for Pasiphae to copulate with a bull which led to the existence of the Minotaur, and he was also responsible for designing the inescapable labyrinth beneath the palace of Minos where the monster was kept. When Theseus escaped the labyrinth, Daedalus rightfully surmised that he would be held responsible by Minos, because only Daedalus would know how to escape the intricate maze. So Daedalus constructed wings by which he and his son, Icarus, might flee and escape from Minos at speeds faster than even the fastest ship in the king’s navy.

Daedalus gave his son sage advice: don’t fly too low or the feathers will absorb moisture from the water and you will fall from the sky. But don’t fly too high or the sun will melt the wax that binds your wings together and you will crash into the sea. The allegory is a popular one across cultures: walk the middle path. Don’t strive to be more than what you are. Bellerophon sought to become a god, and he was struck down when he tried to fly to Olympus. Sisyphus tried to escape death by many means, including preventing his wife from burying him; Zeus ordered him to be tortured in the underworld by tasking him with the chore of rolling a boulder up a hill for eternity. Odysseus famously refused the goddess Calypso’s offer to make him immortal because he recognized that he was human, and to strive beyond what fate had appointed him (death) was to commit the sin of hubris.

The term for Odysseus' diligent behavior in classical philosophy is sophrosunē , moderation, temperence, or prudence. Odysseus knew his place where Sisyphus and Bellerophon did not. Nor, as it turned out, did Icarus. The son of Daedalus failed to heed his father’s advice and flew too close the sun. The wax that bound his wings together melted, and he crashed to his death into the sea. This story serves as an allegory for sophrosunē, knowing one’s place, what it is to be human, and not striving to be more than what you are.

Attic red-figure lekythos by the Icarus Painter (c. 425-400 BCE).

Metropolitan Museum of Art 24.97.37

The identity of the winged figure and of the scene as a whole is unclear. The figure is most often called Icarus or Hypnos. The former seems more plausible, given the contorted pose of the figure and the position of the bird that suggests a precipitous descent.

According to Apollodorus, Ixion, who was already the father of Peirithoös, “fell in love with Hera and tried to rape her.” Zeus created a facsimile of Hera out of a cloud, which Ixion had intercourse with and gave birth to the first of the Centaurs. Ixion was then punished for his hubris, trying to rape Hera certainly qualifies as ignoring the boundary between what is proper for human and ignoring one’s place in the cosmic order. Zeus or Hera, depending on the iteration of the myth, had Ixion tied to a wheel on which he spins for eternity (either in the sky or in the underworld).

© The Trustees of the British Museum

(CC bY-NC-SA 4.0)

Attic red-figure kantharos by the Amphitrite Painter, from Nola (c. 450 BCE). British Museum 1865,0103.23

Athena holds the winged wheel to which Ixion will be affixed while Ares and Hermes presents him to Hera. Hera sits enthroned with a crown. Ares is depicted as a generic hoplite warrior (minus the hoplon shield). Hermes is identifiable by the kerykeion (herald's wand) in his hand and the petasos (traveler's hat) and chlamys (cloak). Athena wears a helmet, peplos and the aegis of Zeus.

The relationship between Theseus and Peirithoös is as old as heroic literature itself, dating all the way back to the 3rd milennium BCE stories surrounding the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh and his faithful friend and questing companion, Enkidu. In a remarkably similar circumstance to the aforementioned Sumerian heroes, Theseus and Peirithoös first met as enemies who, after competing with each other (usually a wrestling contest [agon]), grew to become the best of friends through mutual respect and shared interests in heroic activities. Other popular examples of this pairing in Greek myth include Herakles and Iolas, and Achilles and Patroklos.[7] The relationship is famously employed in modern literature with the questing duo of Frodo and Sam in J. R. R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings.

Theseus and Peirithoös had solidified their friend ship when the latter, a Lapith prince, invited Theseus to his wedding. As we learned from the Ixion story, the race of centaurs were also related to Peirithoös through his father's misguided attempt to rape Hera. Thus, the centaurs were invited to the wedding as well. In Greek myth, centaurs are half man, half beast figures. This makes them closer to the savagery of the natural world. Similar tropes apply to satyrs, barbarians (non-Greeks), and especially barbarian women (e.g., Medea, Amazons). While satyrs are generally portrayed as harmless and comical figures, centaurs are portrayed as particularly war-like and being quick to anger. Like satyrs, centaurs do not live with sophrosunē (moderation). They lack control over their primal or baser natures and, as is the case at the wedding, fail to moderate their consumption of wine (either drinking too much or not diluting their wine with water). Whatever the case, the Centaurs became drunk and tried to rape the Lapith women. The Lapith men, including Peirithoös and aided by Theseus, fended them off. This was known as the battle between Lapiths and centaurs. The event was very popular in Athenian iconography, alongside scenes of Amazonomachies and the Giantomachy. All three mythological battles represented the same theme of Greeks or Olympians championing the cause of justice and civilization against the chaotic threat of bararism, injustice, and savagery.

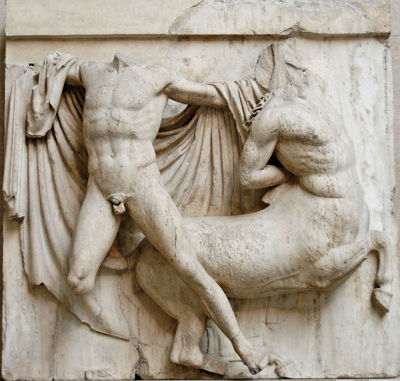

Block X from the south metope, Parthenon. Pentelic marble (c. 447-440 BCE). Louvre Ma 736.

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen (OA)

South Metope 27, Parthenon Pentelic marble (c. 447-440 BCE). British Museum 1816,0610.11.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons

Peirithoös' father, Ixion, committed a serious outrage when he attempted to rape Hera. In Greek mythological thought, the sins of the father were passed onto the son. Entire sagas of heroic geneologies are turned into stories of familial crime and violence that is passed down from one generation to another within the family. The most famous of these sagas are those of Tantalos, whose crimes, their taint, and reciprocal repercussions span from the first generation of humans (Tantalos himself) to the last generation of heroes with Orestes. The other is the house of Cadmos, whose descendants led to some of the most vivid acts of reciprocal violence and kin-killing in the mythology of any culture with Oedipus slaying his father and siring children with his mother. By those standards, the crimes of Ixion and Peirithoös take place in the blink of an eye (just two generations). However, the transgressions and their lesson are quite clear.

For reason that are never clearly explained other than the fact that Peirithoös is his father's son and, therefore, suffers from the same genetic taint of character, "Theseus made an agreement with Peirithous that they would marry doughters of Zeus"[8] The pact that the two heroes made is not in itself outrageous. Theseus targeted Helen, a mortal daughter of Zeus renowned for her beauty when she was 12 years old. However, Peirithoös' choice of bride was utterly perplexing and could only be explained by virtue of the madness that possessed his father to attempt to rape Hera. Peirithoös tried to steal Persephone, the immortal daughter of Zeus, away from Hades as his bride. Hades, like his counterpart on Olympos (Zeus), saw the ignorant and relatively impotent humans coming from a mile away. He tricked them into sitting on chairs from which they were wholly unable to get up.[9] Peirithoös remained trapped in the underworld forever. Theseus, however, was rescued by Herakles who happened to be in the underworld on his final labor to bring Kerberos to the court of Eurystheus.

Attic red-figure volute krater attributed to Painter of Wooly Satyrs (c. 450 BCE). Met 07.285.84

On the neck, battle of centaurs and Lapiths; on the body, an Amazonomachy.

Mythological battles were favored over historical events in Greek art. Here, we see two such battles with relevance to both Theseus and Peirithoös: the Lapiths and Centaurs (neck) and then the Amazonomachy that took place when Penthesilia led an expedition to Athens in order to take back Antiope (body).

Theseus was, to put it mildly, unlucky in love. From the various stories of Ariadne and Antiope to the ill-conceived attempt to kidnap and marry a young Helen, the hero was unable to maintain a steady, healthy, and happy relationship with his female consort. The loss or putting aside of one woman for another is a common theme in the lives of Greece’s most famous mythological figures, Herakles, Jason, and Theseus being the foremost examples. While there are clear similarities between many of the female figures, they do not account for all of the encounters. What does stand out, however, are the relationships that go horribly wrong and end in disaster, usually for both the hero and his consort.

For Theseus, it all started with the rape of Antiope. As we discussed above, the hero either stole or wooed Antiope away during the Amazonomachy in which Herakles acquired the belt of Hippolyte (also known as Ares’ war belt). The pair had a child together named Hippolytos. Somewhere along the way, however Theseus put Antiope aside for the Cretan princess, Phaidra:

[Theseus] had a son Hippolytos with the Amazon woman [Antiope], but from Deucalion he later got Minos daughter Phaidra, and when his wedding to her was being celebrated, his Amazon ex-wife showed up dressed for battle with her Amazonian companions and intended to kill the guests. But they quickly shut the doors and killed her. But some say that she was killed by Theseus in battle. [10]

With Antiope out of the picture, Theseus was free to marry and sire new children with Phaidra, but his child with Antiope remained in his household and seemed to be a dutiful son. However, Phaidra famously fell in love with her stepson, and when he rebuffed her advances, she accused Hippolytos of having raped her.[11] The Apollodorus version continues:

Theseus believed her and prayed to Poseidon that Hippolytos be destroyed. As Hippolytos rode on his chariot and was driving next to the sea, Poseidon sent forth a bull from the waves. The horses were spooked and the chariot was smashed to pieces. Hippolytos, tangled in the reins, was dragged to his death. Phaidra hanged herself when her love became public knowledge.

Although not entirely bereft of heirs (his two sons by Phaidra still survive) Theseus finds himself in a very similar and unenviable position as Herakles and Jason in their later years. Their family lives were left in ruins and, for the most part, for reasons of their own making.

These eerily similar tales about the failures and losses of Greece’s mythological heroes, with regard to love and happiness, reflect a theme common throughout the klea andrōn: human life is defined by suffering, and human beings are prone to errors or mistakes.[12] In this sense, the mythological tales of heroes were a gold mine for the tragic stage: the tragedy of human life (and death) is woven into the very fabric of all the klea andrōn. The Iliad is often referred to as the tragedy of Achilles and/or Hector; Herakles dies a horrible, agonizing death atop a pyre; and the most famous story of any hero’s suffering is that of Odysseus in the Odyssey, whereby he earns the epithet “long-suffering Odysseus.” That the suffering of our heroes is brought on by their all-too-human-ignorance, thier choices and actions only reinforces the tragic lessons of human nature in these myths.

[1] Humanly flawed warriors who both suffer greatly and perform great acts of valor centered around Greek ideals of the aristocratic athlete – all while championing civilized Greek life in juxtaposition to the savage “other.”

[2] This phenomenon is neither new nor unique to Herakles. It applies to many heroes across cultures and most of the gods in the Greco-Roman pantheon.

[3] Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames and Hudson (1991).

[4] Anthology of Classical Myth 1st ed. Hackett (2004).

[5] Apollodorus. "Epitome 1: Events and Genealogies from Theseus." in Apollodorus' Library and Higinus' Fabulae: Two handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans & eds). Kindle edition. Hackett (2007).

[6] ibid.

[7] Caroline Alexander. The War that Killed Achilles: The True Story of Homer's Iliad and the Trojan War. Penguin (2009).

[8] Apollodorus. "Epitome 1: Events and Genealogies from Theseus." in Apollodorus' Library and Higinus' Fabulae: Two handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans & eds). Kindle edition. Hackett (2007).

[9] Hera was trapped in a somewhat similar manner on a golden throne crafted by Hephaistos. Many myths borrow mechanics or plots from each other.

[10] Apollodorus. “Epitome 1.” In Apollodorus’ Library and Hyginus’ Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (eds. and trans.). Hackett (2007).

[12] What Aristotle would narrowly define as hamartia in the plot of a successful tragedy. Aristotle. The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary. Stephen Halliwell (Trans.). North Carolina UP (1987).