Right: Apulian red-figure ceramic plate by Phrixos Group (c. 340 BCE). Apotheosis of Herakles. The hero rides a chariot to Olympos driven by Athena and accompanied by Nike.

Berlin 1984.47 Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol.

Deianeira was the daughter of Oineus, the king of Kalydon. According to Apollodorus, she was the child of Dionysos and Althaia, Oineus' wife. Thus, she is the sister (or half sister) of Meleager. And like Meleager, her story is not a particularly happy one. In Apollodorus' account, Deianeira was akin to Atalanta in that she engaged in activities traditionally the province of men in the Greek world: "Deianeira drove chariots and trained for war; Herakles wrestled with Acheloos to see who would marry her."[1] Her exploits in battle and chariot racing are greatly overshadowed by her role as a "trophy wife" in the archetype of Helen of Sparta/Troy. Apollodorus and Sophocles agree that Herakles wrestled the river god Acheloos for Deianeira's hand in marriage:

"When Herakles came to Kalydon, he became a suitor for Deiandeira, Oineus' daughter. For her hand in marriage he wrestled with Acheloos, and when he changed himself into a bull, Herakles broke off one of his horns. He married Deianeira, and Acheloos got his horn back by tading it for the horn of Amaltheia." [1]

The contest between Herakles and Acheloos is recorded on a few surviving vases in both black- and red-figure as well as other media (see gallery below). Like Helen and Atalanta, Deianeira's fate was to be associated with death and destruction for the men who loved her. The most famous (and tragic!) account of Deianeira survives in the 5th century tragedy of Sophocles, Tracchiniae (translated "Women of Tracchis," named after the Chorus of the play).

Deianeira's role in myth as a trophy is emphasized in the previous episode, in which Herakles won her hand in marriage through a contest with the river god Acheloos. This status as prize or commodity is reinforced by the next episode in her story. Herakles was returning home with his newly won bride when they came upon the swollen river of Euenos. As it happened, Nessos, a centaur, set himself up as a ferryman to bring travelers across the river for a fee. He offerred his services to Herakles who gave over Deianeira to the centaur. Nessos, however, had other plans in mind and attempted to steal or rape the woman. In Sophocles' version, Herakles struck down the centaur with one of his arrows that was tipped with the poisonous blood of the Lernean Hydra (a token he picked up on his second labor to Eurystheus). The duplicitous or savage behavior of Nessos in his attempt to rape Deianeira fits with Greek mythological depictions of centaurs as violent, quick to anger, quick to drink, and generally having beastial disposition (they were, after all, half human and half beast). So his offer to ferry Deianeira across the river would be seen by the ancient Greeks as a duplicitous act from the outset much as the spectators of the Elizabethan stage would see the actions of the hunchbacked Richard III's actions in the play Richard III. This is a literary device known as physiognomy. The visual narratives of this episode generally agree with Sophocles' version with the minor exception that Herakles is normally depicted slaying Nessos with his sword or club. The bow and arrow, if he used them, are generally absent in the condensed surface area of vase paintings. Two examples of such paintings are discussed below.

Attic black-figure neck-amphora (c. 510 BCE).

"According to myth, the centaur Nessos attacked Deianeira and Herakles rescued her, shooting the beast with an arrow poisoned with the Hydra's blood. But on this particular vase and on most illustrated depictions of this myth, Herakles attacks Nessos with his sword." Herakles' use of poisoned arrows is integral to surviving textual narratives surrounding the hero's death. However, the vase painting medium makes such depictions difficult to pull off effectively due to the compressed space in which the painter has to work.

Proto-Attic neck-amphora attributd to the New York Nessos Painter (c. 660 BCE).

MET 11.210.1. Detail images credited to Mary Harrsch. (CC BY 2.0).

"The painter has shown the centaur [Nessos] collapsing (on the left) as Herakles advances to attack him with his sword, while Deianeira, on the other side of the hero, demurely holds the reins of the four-horse chariot."[2]

Proto-Attic refers to a transitional technique of decoration from the rigid, stylized decoration of geometric art popular in the 8th century BCE to the profusion of figuaral narrative scenes, including mythological narratives, using the black-figure technique. This vase is painted in part with the incision of black silhouettes characteristic of black-figure, but also outlined figures with painted details that led away from the solid silhouettes of geometric figures to the eventual dominance of the black-figure technique. Hence, "Proto-Attic" really means proto-black-figure, where artists were experimenting and exploring techniques that eventually became black-figure. Similarly, the transition from Orientalizing themes and motifs of floral and animal figures toward the human figural depictions of mid-Archaic and Classical narrative art.

The story told of Herakles' death by Apollodorus is very similar to the surviving play on the same subject by Sophocles, and it is probable that the Sophoclean version grew to become the dominant version of the myth after the popularity of the dramatist's 5th century tragedy. For simplicity's sake, we will follow the events in Apollodorus. After Herakles completed his labors to Eurystheus and freed himself from various other obligations, he went to war with Eurytos, the ruler of Oichalia. Before Herakles married Deianeira, he had won an archery contest in the house of Eurytos for which the prize was the hand in marriage of the king's daughter, Iole. But Eurytos refused to give his daughter over to him out of fear that Herakles would repeat his madness, murdering Iole and any children they had together just as he had done with Megera and their childern earlier in Herakles' career. In the intervening years, Herakles married Deianeira, but he never forgot the slight done to him by Eurytos. Here, both Sophcles and Apollodorus agree that Herakles attacked Oichalia, slew Eurytos and his heirs, and then took Iole to be his new wife (or concubine?). Deianeira was made aware of Herakles' intentions to "replace" or "demote" her as his lover, and she took action to prevent it.

This is where 5th century tragic versions of myths thrive; they juxtapose existing cultural beliefs or practices with each other, exposing their contradictions and the moral impasse that such beliefs and practices create. For in Apollodorus' words, "Just before he died, Nessos called Deianeira over and told her that if she ever wanted a love potion to use on Herakles, she should mix the seed that he had discharged onto the ground with the blood that was flowig from the arrow wound. She did this and always kept it nearby."[3]

This was a trick, of course. Nessos' blood was poisoned by the blood of the hydra. But years later, as Herakles was returning to their home in Tracchis with the younger woman and prize (Iole) in tow, Deianeira, "thinking that Nessos' spilled blood really was a love potion, anointed the tunic with it. Herakles put it on and began to make sacrifice, but when the tunic grew warm, the Hydra's poison ate away his flesh."[4] This event brings about the death of Herakles. Although his actual death occurs on a funeral pyre, burning on the pyre was an attempt to escape the agony of poisoned tunic and the ignominy of being slain by a woman.

This episode is so emblematic of Greek tragedy because it is the first time in her myth that Deianeira plays an active role in her own story.[5] Up to this point, she is a trophy or possession who is passed back and forth (or stolen) from one man to another, be it her father, Acheloos, Herakles, or Nessos. Yet it is when she attempts to assert control over her life as a active participant (or agent) that things go horribly awry. She is well intentioned. She is in love with Herakles and certainly means him no harm - the ideal wife to that point. Indeed, she does nothing to harm Iole, a younger version of the beautiful prize; she feels nothing but pity for the girl. Rather, Deianeira brings about Herakles' death and kills herself out of guilt and shame when she realizes the trick that Nessos has played on her; even her decision to commit suicide in an indication that she has fully internalized the dominant moral/ethical code of her day.

The tale, as 5th century tragedies do so very well, asks its audience to sympathize with a tragic figure who very clearly violates the norms and mores of society. Doing so implicitly asks the audience to question the validity of their long held beliefs and practices. It somewhat oversimplifies the matter to state that epic (e.g., Homeric epic) affirms whereas 5th century tragedy questions, because there are quite famous moments in both the Iliad and the Odyssey in which circumstances develop that clearly question the dominant ideology of the poems (e. g., Achilles' obstiancy, Hektor's decision to fight Achilles). Yet the epic form does tend, by and large, to perpetuate social ideaology and practices whereas the 5th century Athenian tragedies seem almost to revel in the deconstruction and critical analysis of them.

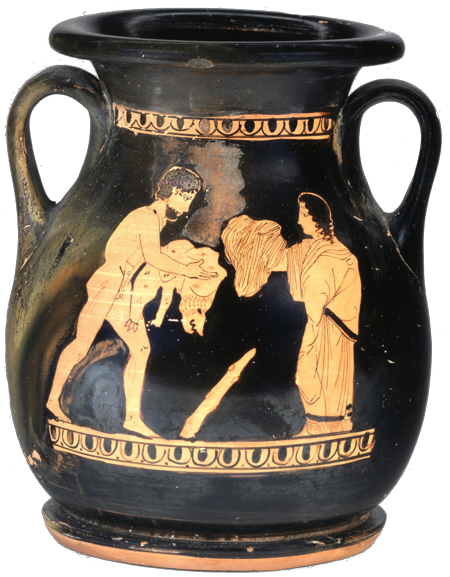

Attic red-figure pelike (c. 430 BCE).

London 1851,0416.16

"Herakles has removed his lion's skin and dropped his club, and steps forward from left to receive a rolled up robe (the poisoned shirt of Nessos) which a figure, most probably a female servant rather than Lichas (Herakles' male servant), standing on right offers him" (British Museum). The robe was a gift from Deianeira.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, background removed.

[1] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two handbooks of Greek Mythology. Trans R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma. Hackett (2007).

[2] Susan Woodford. An Introduction to Greek Art: Sculputre and Vase Painting in the Archaic and Classical Periods. 2nd Edition. Bloomsbury (2014).

[3] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two handbooks of Greek Mythology. Trans R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma. Hackett (2007).

[4] ibid.

[5] Apollodorus briefly mentions that Deianeira was an Atalanta-like figure in that she "drove chariots and trained for war" in her youth, which might have been used a a precursor for the unnatural carnage that she would unleash by violating her gender role later in life. In this, her mythological corpus is similar to Medea, who built up quite a reputation for violating cultural taboos and gender expectations before ultimately slitting the throats of her own children in order to spite her former lover, Jason. However, Deianeira's actions are never depicted to be so vindictive in any version of her story that I am aware.