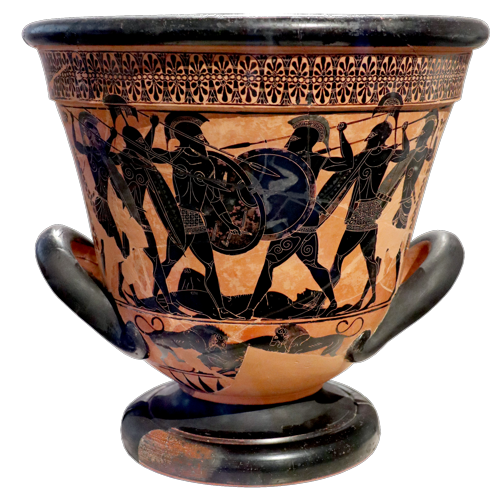

Attic black-figure kalyx krater in the manner of Exekias (c. 530 BCE). Athens 26746.

Photo: George E. Koronaios. Copyright: (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Homeric battle around the body of a dead warrior, probably Patroclus.

Book 17, which is omitted in our abridged version of the epic, consists of a massive struggle over Patroclus’ corpse. Book 18 begins with Antilochus delivering the news of Patroclus’ death to Achilles:

“Son of wise Peleus, this is painful news

For you to hear, and I wish it were not true.

Patroclus is down, and they are fighting

For his naked corpse. Hector has the armor.” (19-22)

Patroclus is dead. His armor has been stripped by Hector. The Greeks and Trojans now battle over his corpse, literally and figuratively (Athens 26746, above). We know from Book 16 that Patroclus was disarmed by Apollo. We also noted that while Euphorbus – not Hector – struck the crucial blow, it was Hector who remained over the corpse to collect the armor. The poem conspicuously noted that Euphorbus retreated as soon as he struck the decisive blow, afraid of Patroclus despite his debilitated condition. Hector, however, was willing to stand fast, controlling the area long enough to collect the armor. There are layers of significance here, both to the plot and to the timorous culture of the Iliad.

In the warrior culture of the poem, degrees of honor are allotted for different types of combat. In particular, close quarter combat with spear, sword, and shield is viewed as more dangerous and, thus, more rewarding than ranged combat with bow and arrow. The logic is straightforward: an archer risks himself to a much lesser degree when attacking a foe at range than the infantryman does in close combat with spear and shield. However, both the tangible and intangible rewards are greater for the victor in close quarters. To defeat an opponent in close quarters makes it possible to strip the corpse of its armor, which serves as the de facto trophy in the Iliad. The close quarters kill also entails greater risk and, thus, requires more courage and physical prowess. This is reflected in the higher esteem given to the warrior who is victorious with spear and shield rather than the bow.

The fact that Hector, not Euphorbus, now possesses the armor is significant. Hector may not have delivered the deciding blow, but he was the Trojan courageous enough to finish the job and collect the armor. Trophies are similar to signs or tombstones; they announce or declare a thing (victory), and they do so with the intent to memorialize the deed. In other words, a gold medal has no intrinsic relation to a 50 meter sprint. But that medal is often engraved with the finishing position, event, and date. It is an arbitrary token given meaning by symbolically attaching it, via the engraving, to an otherwise unrelated deed. Its purpose is to remind those who see it of one’s victory in a certain event at a certain venue on a certain date. Likewise, a gravestone has no intrinsic relation to a dead man, but it is engraved with text that is designed to remind passersby of the deceased person’s existence (e.g., “here lies John Doe, 1995-2026. Loving father.”).

In the case of Patroclus’ armor – which actually belonged to Achilles – the trophy that Hector now wears serves as a declaration of his victory over Patroclus. Every Greek and Trojan who sees Hector wearing the armor that he took from Patroclus is reminded that Hector killed Patroclus. The armor, as a trophy, functions as a gravestone or a billboard: “I, Hector, son of Priam, slew Patroclus.” Seeing Hector in the god-forged armor of Achilles that was stripped from Patroclus’ corpse renders the roles of Apollo and Euphorbus moot in regard to whom the Greeks and Trojans hold responsible (or honor) for slaying Patroclus. Hector possesses the armor; that also means it is Hector, not Euphorbus, who becomes the object of Achilles’ rage.

Rage and sorrow are familiar bedfellows. They are, however, different emotions. Studying the latter can shed light on the former for Achilles. That is to say, his rage is not the only emotion in which the mighty warrior indulges to excess of cultural norms. Take his immediate reaction to the news of Patroclus’ death, for example:

A mist of black grief enveloped Achilles.

He scooped up fistfuls of sunburnt dust

And poured it on his head, fouling

His beautiful face. Black ash grimed

His finespun cloak as he stretched his huge body

Out in the dust and lay there,

Tearing out his hair with his hands.

The women, whom, Achilles and Patroclus

Had taken in raids, ran shrieking out of the tent

To be with Achilles, and they beat their breasts

Until their knees gave out beneath them.

Antilochus, sobbing himself, stayed with Achilles

And held his hands – he was groaning

From the depths of his soul – for fear

He would lay open his own throat with steel. (23-37)

Achilles is the child of a man and goddess, and as such, he acts with greater magnitude than other mortals. He fights harder than other men. He loves deeper. He rages more intensely, and he mourns to a degree that exceeds cultural expectations. Everything Achilles does seems to go beyond societal norms, not just his rage, albeit the latter is the most common example. Here, we see that even Achilles’ mourning in the Iliad exceeds gender expectations and threatens the community.

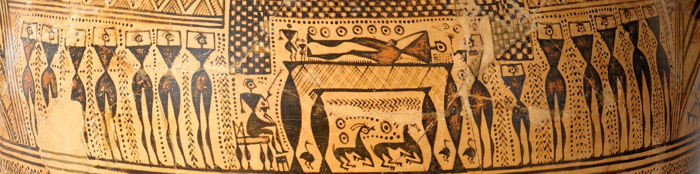

Achilles’ reaction to the death of Patroclus is gendered in its expressiveness and in the threat to the community that indulging in his sorrow entails. Upon learning of his beloved friend’s death, Achilles collapses to the ground, pouring dirt about his body, and pulling out his hair as he lay crying and moaning. This reaction is not necessarily gendered in itself. There is a clear example from the 8th century BCE of a Geometric funeral marker depicting friends of the deceased possibly pulling out their hair as they ritually mourn the dead (see inset below).

Detail of a Geometric terracotta krater attributed to the Hirschfeld Workshop (c. 750-735 BCE). MET 14.120.14.

“Monumental grave markers were first introduced during the Geometric period. They were large vases, often decorated with funerary representations. The main scene occupies the widest portion of the vase and shows the deceased laid upon a bier surrounded by members of his household and, at either side, mourners" (MET).

A distinctive feature of early Geometric figural art is the triangular silhouette for a chest. All Geometric art is characterized by copious bands of geometric patterns such as those above and below the funerary scene.

The Iliad was composed during the same era as this vase (latter half of the 8th century), but Book 18 conspicuously shows us Achilles as the lone male to befoul his face and pull out his hair. The women of his “house” (servants won in battle such as Briseis would have been) rush out to join him in this activity while the lone male warrior other than Achilles, Antilochus, stands stoically by, afraid that Achilles might kill himself, thus imperiling the community (Greek fleet) further. Even his mother, Thetis, and the rest of the Nereids,[1] wailed and beat their breasts. Achilles is conspicuous as the only male to engage in such visceral shows of emotion.

Thetis is a goddess wed to a man, immortal to mortal. Her love for her husband and her son ties Thetis to mortality in an unnatural way. The following episode with Thetis reinforces the lesson from the Long Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.

In the latter, Aphrodite reluctantly falls in love with a mortal, Anchises, a Trojan lord and cousin to Priam. They sleep together for only one night, but in the episode, Aphrodite seduces Anchises and sheds tears of sorrow as she takes him to bed. The next morning, she reveals that she is pregnant with a mortal child, who will be left in the care of Anchises sometime before he matures. Aphrodite tells Anchises, “Aineias shall his name be, since dread sorrow held me when I came into the bed of a mortal man.”[2] Aineias is derived from the Greek word ainos, “dread sorrow.”[3] Aphrodite is filled with dread[4] when she sleeps with the man whom she seduces. The resultant child of that union, Aeneas, is a bittersweet object of this same dread. Both the lover and the child are mortal whereas Aphrodite is immortal and ageless.

Gods dread love affairs with mortals because it forces them to deal with the consequences of mortality, feelings that are foreign to the gods’ natural state of being. Aging and death are not naturally part of the gods’ lives. However, when they form emotional bonds with mortals, the aging and death of their loved ones causes psychological trauma, just as mortals are traumatized by the suffering of friends and family. The difference is that gods do not, by nature, die, whereas mortals do. Thus, the gods are not naturally equipped to cope with the aging and loss of loved ones. For this reason, no god wants to fall in love with a mortal, and if they do (e.g., Eos and Tithonos,[5] Calypso and Odysseus[6]), they may even try to subvert the natural order to avoid such emotional pain.

Thetis expresses this same psychological trauma in a much more compact way during Book 18 of the Iliad:

“Hear me, sisters, hear the pain in my heart.

I gave birth to a son, and that is my sorrow,

My perfect son, the best of heroes.

He grew like a sapling, and I nursed him

As I would a plant on the hill in my garden,

And I sent him to Ilion on a sailing ship

to fight the Trojans. And now I will never

Welcome him home again to Peleus’ house.

As long as he lives and sees the sunlight

He will be in pain, and I cannot help him.

but I’ll go now to see and hear my dear son,

Since he is suffering while he waits out the war.” (56-67)

Thetis leaves her deep sea abode for the beached ships to console her son and asks him why he is so upset. After all, Agamemnon has been embarrassed and forced to recognize Achilles’ value to the army. Achilles replies,

“Mother, Zeus may have done all this for me,

But how can I rejoice? my friend is dead,

Patroclus, my dearest friend of all. I loved him,

And I killed him. And the armor –

Hector cut him down and took off his body

the heavy, splendid armor, beautiful to see,

That the gods gave to Peleus as a gift

On the day they put you to bed with a mortal.

But now – it was all so you would suffer pain

For your ravaged son. You will never again

Welcome me home, since I no longer have the will

to remain alive among men, not unless Hector

Loses his life on the point of my spear

And pays for despoiling Menoetius’ son.” (83-98)

It is ironic that Achilles received from Zeus exactly what he asked of the deity and was promised by Athena in Book 1. The Iliad shares with 5th century Athenian drama what is referred to as the tragic world view. This link is particularly strong in Sophoclean tragedies, which are defined by human ignorance. Humans in Sophocles’ plays are characterized by their inability to understand the true meaning of their actions or circumstances. In his pursuit of honor and the humiliation of Agamemnon, Achilles unwittingly brought about the death of his dearest friend (“I loved him, and I killed him”).

In bemoaning his own ill fortune, Achilles reiterates the problem of romance between mortals and immortals that we discussed above. He frames Thetis’ love for Peleus as a curse that would bind her to suffering through her connection to frail, ephemeral mortals: “it was all so you would suffer pain for your ravaged son.”

This connection to mortal suffering has indeed ensnared Thetis, and she warns Achilles that his death is fated to follow soon after that of Hector’s. Achilles replies:

“Then let me die now. I was no help

To him when he was killed out there. He died

Far from home, and he needed me to protect him.

But now, since I’m not going home,

[…]

I wish all strife could stop, among gods

And among men, and anger too – it sends

Sensible men into fits of temper,

It drips down our throats sweeter than honey

And mushrooms up in or bellies like smoke.

Yes, the warlord Agamemnon angered me.

But we’ll let that be, no matter how it hurts,

And conquer our pride, because we must.

but I’m going now to find the man who destroyed

My beloved – Hector. As for my own fate,

I’ll accept it whenever it pleases Zeus

And the other immortal gods to send it.

[…]

But now to win glory

And make some Trojan woman or deep-breasted

Dardanian matron wipe the tears

From her soft cheeks, make her sob and groan.

Let them feel how long I’ve been out of the war.

Don’t try, out of love, to stop me. I won’t listen.” (103-135)

This reply touches on many of the themes and motifs that we have dealt with over the course of the poem. In the first four lines, Achilles expresses a desire for death while in the depths of his despair. This is the Achilles we encountered at the outset of Book 18, a man given over entirely to mourning to the extent that his own life, let alone the survival of his community (the army), is inconsequential. In fact, one could read into this the desire for death in a world without Patroclus. Antilochus certainly thought suicide was a real possibility.

The next topic is anger itself. We noted in Book 9 that Achilles is a highly intelligent and psychologically complex hero. He enjoys a self-awareness brought on by his own suffering that other heroes in the epic cannot “enjoy.” Throughout this commentary, we have noted a complex interrelationship between logic, emotion, and action. Achilles does so himself in his reply to Thetis: he directly acknowledges the effects of anger, how the emotion has affected both his and Agamemnon’s decisions throughout the Iliad. In Achilles’ own words, anger “sends sensible men into fits of temper.” But there is a bitter desire to feed that anger, as if satiating oneself with the sweetness of honey, only to discover that, when the honey reaches one’s belly, it was a lie, a deception, not honey but poison, an arsenic that burns and destroys rather than nourishes and replenishes.

Finally, Achilles announces his intention to take revenge on Hector for the death of Patroclus. Achilles’ life means little and less to him at this point. Hector’s death will be compensation enough for his short life – that and to win glory on the battlefield in the process. Achilles’ great glory in battle will come at the expense of many Trojans. He will bring death, both to Hector and the Trojans as well as himself; and sorrow to his mother, the Trojan wives, children, and mothers alike. In a sense, Achilles has returned to the fold: “we’ll let that be, no matter how it hurts, and conquer our pride because we must.” He will fight on the battlefield, accruing the honor and glory for which all warriors fight. Yet he does so with the expressed purpose of revenge, an action motivated by anger, after having just detailed the ways in which anger manipulates human action in a deeply negative way.

The remainder of Book 18 details the forging of Achilles new armor by Hephaestus. The details on the shield are given particular attention and are well worth an essay in and of themselves. We will not attempt such an endeavor in this commentary.

[1] Nereids are children of the sea god, Nereus. He famously sired 50 females, sea nymphs. Thetis is the most famous of them.

[2] Palaima, Thomas G.. Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation (p. 201). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

[3] Aeneas is the Latin spelling of the Greek Aineias.

[4] Dread, like fear, is a forward-looking emotion. Aphrodite sees pain in her future that will be brought on by her relationships with Anchises and Aeneas.

[5] Eos, the Dawn, fell in love with the mortal Trojan Tithonos. She tried to make him immortal but forgot to make him ageless, so the man grew continually old and enfeeble but could not die.

[6] Caplypso falls in love with Odysseus in the Odyssey and offers to make him ageless and immortal if he will remain with her on her island as her consort.