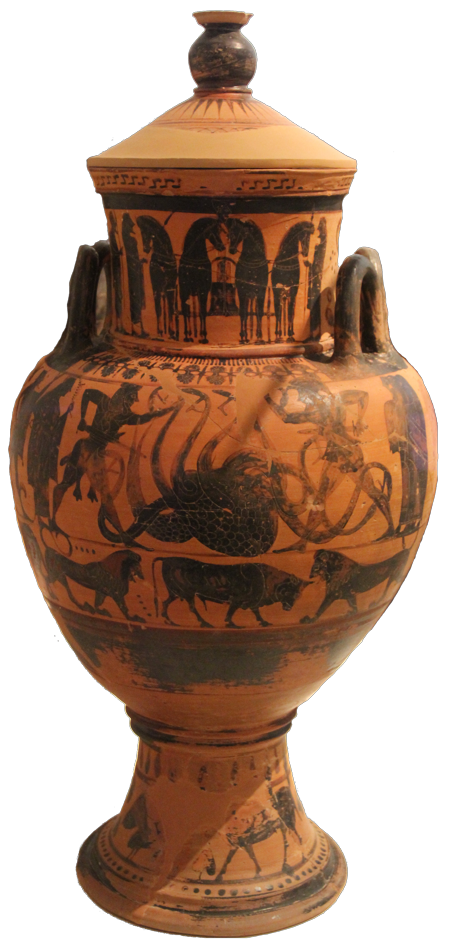

Right: Attic red-figure volute krater attributed to Kleophrades Painter (c. 480-470 BCE).

Scenes from the labors of the Greek hero Herakles encircle the neck of this Athenian red-figure volute-krater. From left to right: Keryneian hind, Lernean hydra, Nemean lion.

The 12 labors are a series of exploits or quests that Herakles performs in service to his cousin, Eurystheus, the king of Mycenae. Although many of the various labors included in this set occur in literary and visual art from a very early point in the Archaic period, “Herakles’ canonical twelve labours do not seem to be established in Greek myth before the classical period.”[1] In other words, the ordering of the exploits and the in-/exclusion of the specific labors didn’t reach the set of twelve that we know them as today until the 5th century BCE.

Along with being the most famous exploits of Herakles’ career, these are also the deeds Herakles performs because of Hera’s wrath. Herakles’ first wife, Megara, was a daughter of Creon, the king of Thebes, and the couple had three children. Things were looking up for the mortal son of Zeus and Alkmene...until they went horribly wrong. Apollodorus explains:

Heracles was driven mad because of the jealousy of Hera. He threw his own children by Megara into a fire, along with two of Iphicles’ sons. For this he condemned himself to exile. He was purified by Thespios, and going to Delphi, he asked the god where he should settle. The Pythia then for the first time called him by the name Heracles; up until then he had been called Alceides. She told him to settle in Tiryns and serve Eurystheus for twelve years. She also told him to accomplish ten labors imposed upon him and said that when the labors were finished, he would become immortal. [2]

Although his madness was heaven-sent, Herakles was still guilty of prolicide (killing his children) and uxoricide (killing his wife). Kin-killing was a particularly grave crime in the Greek world, and it fell under the purview of the Erinyes (Furies), monstrous female deities who tortured men and women guilty of spilling the blood of their kin.

In Apollodorus’ version of the tale, Herakles was purified of the crime by Thespios, a nearby king with connections to Athens, and he sought advice from the Pythia only to learn where he should resettle as he remained a taint to his home of Thebes. It was a common practice even in the historical periods to consult the Delphic oracle before setting out on an expedition to found a new polis or find a new home. Herakles’ move to consult the oracle can be viewed as participating in such a ritual in looking to settle a new territory. The priestess christened his new name and directed him to settle at Tiryns (a smaller city within the sphere of influence of Mycenae, where Alkmene and Amphitryon were originally from).

However, Apollodorus’ wording is a little confusing. Did Herakles simply ask the Pythia where to live, now that he was exiled from Thebes? Or did he do so out of concern that the purification performed by Thespios was not enough? Modern interpretations tend toward the latter and go so far as to ignore the Thespios purification or treat it as a legal vindication rather than a spiritual one...or they ignore the Thespios purification altogether in an attempt at simplification. In this rationalization, Herakles served Eurystheus as a form of penance to appease the bloodguilt of having killed his wife and children. However, if we follow Apollodorus more literally, Herakles went to serve Eurystheus in order to achieve glory and immortality - not to expurgate the spiritual taint caused by killing his kin, which was already done by Thespios.

Attic red-figure volute krater attributed to Kleophrades Painter (c. 480-470 BCE). Getty 84.AE.974

This is the opposite side of the volute-krater shown at the top of this page. On the left, Iolaos drives on some of the cattle while Herakles, backed by Athena, moves toward the sleeping giant Alkyoneus. A small winged figure of Hypnos (Sleep) crouches atop the giant's chest to reinforce the fact that he is asleep. This was one of the many "side labors" (exploits of Herakles that were not part of the canonized 12 labors for Eurystheus).

In any case, “[t]hese tasks were the twelve labours for which Herakles would become best known, each involving the killing of a monster or the fetching of an impossible prize.”[3]

The labors Herakles performs for Eurystheus are primarily monster slaying quests, and they represent, in a fairly straightforward way, the hero cleansing the land of savage threats to human civilization. These labors include slaying the Nemean lion, slaying the Lernaean hydra, slaying the Stymphalian birds, and slaying the monster Geryon. A fourth labor represents a slight variation on this theme by capturing the mares of Diomedes. Diomedes was a Thracian king who fed travelers to his horses (the mares). This was a perversion of xenia (hospitality), and Herakles famously visited justice upon Diomedes by feeding him to his own horses before binding their mouths shut and putting an end to the perverse practice.

Yet another twist on the monster slaying exploit occurred in the episodes with the golden hind of Artemis (a deer sacred to the goddess), the Erymanthian boar (a giant boar that wreaked havoc in Erymanthia), and the Cretan Bull. These labors required Herakles to battle ferocious creatures, but rather than kill them, he brought them back alive to Eurystheus. Once again, the exploits highlight the hero’s strength in a contest against savage nature, but the civilizing impact of the deeds is dubious. The Cretan bull, in particular, seemed to cause more harm for mainland Greece, which would eventually need to be delt with by Theseus.

The belt of Hippolyta, which was also called the war belt of Ares, was the object of Herakles’ 9th labor, and it was yet another variation on the theme of civilized versus savage. In this case, however, it was a battle between the “civilized” Greek male (Herakles and his companions) and the barbarian Asiatic female (Amazons). Anyone who did not speak Greek was viewed as a “barbarian,” and an Asiatic society dominated by female warriors was viewed as particularly barbaric or uncivilized by Greek standards.

There were a few outliers in the labors, as regards the civilized and savage motif: the stables of Augeus, the apples of the Hesperides, and Kerberos. We will briefly analyze each labor for the remainder of this section. But even the latter two included the hero venturing beyond the borders of civilization, realms proper for human habitation, experiencing wondrous encounters, and returning from such places that would have been impossible for a normal human.

The remainder of this page is comprised of brief overview and analysis of each labor and a comparison between Apollodorus' version of the story and at least one version from sculpture or painting:

Apollodorus' version of this labor is fairly straightforward: The lion was the offspring of Typhon, a monstrous god that almost overthrew Zeus, and it was said to be invulnerable. Herakles confirmed this when he was unable to penetrate the lion's hide with an arrow. Visual and literary narratives vary slightly in what happened next, either Herakles wrestled the creature and choked it out with his bare hands, or he clubbed it unconscious with his trusty club. Apollodorus mentions the club briefly but goes with the version in which Herakles wrestles the beast and chokes it to death. This is also the most dramatic scene chosen by visual artists. On the other hand, Theocritus, a Hellenistic poet, told a version by which Herakles stunned the lion unconscious with his club before strangling it to death and then used its own claws to skin the otherwise impenetrable hide, which he wore as armor from that point forward (his most identifiable attribute). Apollodorus, however, attributes Herakles' signature lion skin to a similar but earlier encounter with a lion that was causing trouble around Mt. Kithairon. Most sources and scholars discount that version for the origin of Herakles' lionskin cloak, presumably because it lacks the poetic flare and dramatic irony of making the impenetrable hide of the Nemean Lion into one's similarly impenetrable armor. Nevertheless, there are a vast number of visual depictions (mostly vase paintings and some sculpture) from Archaic and Classical Greece. They mostly depict the hero as nude or without the lionskin during the encounter with the lion, but he wears it conspicuously in every other labor; see, for example, the volute-krater at the top of this page that depicts a number of Herakles' labors (including the Nemean Lion).

Lastly, the cloak serves as a tangible representation of the hero's increasing strength and experience. Indeed, the exploits of Herakles and his fellow heroes (from India to the British Isles) are the framework upon which modern role playing games (RPGs) such as Dungeons and Dragons and World of Warcraft are based. In these RPGs, player characters play the role of the hero (e.g., Herakles), and level-up their charcter, gainng power and experience through various means (usually slaying increasingly more powerful beasts), and in the process of leveling-up, the player acquires tokens (weapons, shields, potions, flying sandals, etc.) that allow the hero to accomplish more difficult tasks - just like their prototypes in Greek, and Near Eastern myth.

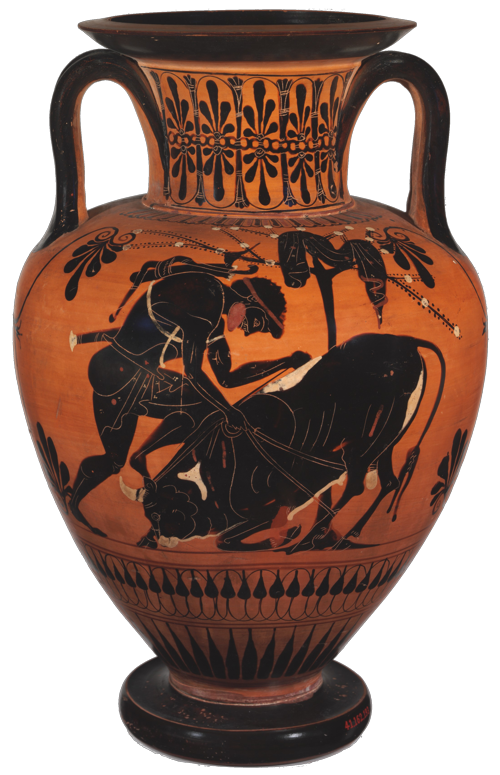

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to Painter of Berlin 1899 (c. 515-510). Cleveland 1970.16.

Left: A nude Herakles with particularly muscled legs and arms wrestles the Nemean lion in front of Athena (flesh painted white). Iolaos looks on from the left, holding the hero's club.

Right: Herakles leans on his club with the lion skin wrapped about his forearm as he looks over his shoulder at the lion whose paw reaches toward him.

This sculpture compresses time. We see the two contestants (Herakles and the lion) as well as the result (Herakles triumphantly carries the lion's skin on his arm).

1st century CE schist wrestler's weight from Pakistan (ancient Gandhara). Met 1994.112.

The Nemean lion is the most popular exploit of Herakles' labors. In fact, it is depicted more in Archaic and Classical vase painting than any other mythological scene in surviving Greek art.[4] The following is a small sample of the many surviving depictions from a handful of libraries with online collections. This scene is seemingly everywhere.

late 6th century BCE black-figure hydria (Met 74.51.1331).

c. 500 BCE black-figure neck-amphora (Met X.21.15).

c. 500 BCE black-figure neck-amphora (Met 41.162.212).

c. 530-520 BCE black-figure amphora (Met 17.230.7)

c. 540 BCE black-figure amphora (Met 40.11.20)

Early 5th century BCE black-figure oinochoe (Met 06.1021.66)

c. 540 BCE amphora (Met 56.171.11)

c. 450 BCE carnelian scarab (Boston MFA 27.722)

early 4th century BCE Etruscan carnelian scarab (Boston MFA 27.723)

c. 430-320 BCE Etruscan carnelian scarab (Boston MFA 01.7605)

c. 530-510 BCE black-figure kylix (Boston MFA 60.1172)

c. 460-400 BCE stater (coin) (Boston MFA 04.1332)

c. 510-500 black-figure neck-amphora (Boston MFA 1970.69)

c. 535-520 black-figure cup (Louvre F 167) - This one's interesting. Herakles is shown with club and bow, not wrestling the lion.

c. 550-540 BCE black-figure oinochoe (Louvre F37)

c. 510 BCE red-figure kylix (Louvre G 71)

c. 470 BCE metope (Louvre Gy 0098)

c. 50 BCE-50 CE bas relief (Louvre Cp 4176)

c. 200-300 CE sarcophagus relief (Louvre LP 2603)

c. 550-530 BCE black-figure kylix(?) (Louvre CA 7309)

c. 525-500 BCE black-figure Oinochoe (Louvre F 349)

c. 525-500 BCE black-figure hydria fragment (Louvre Cp 10229)

c. 525-500 BCE black-figure skyphos (Louvre Cp 10294)

c. 500-475 BCE black-figure white-ground lekythos (Louvre L 31)

c. 550-540 BCE black-figure kylix (Louvre F 91)

c. 550 BCE black-figure amphora fragment (Louvre S 6594)

c. 525-500 BCE black-figure kyathos (Louvre Cp 12111)

c. 500-475 BCE black-figure kylix fragment (Louvre CA 3103)

c. 530-520 BCE black-figure amphora (Louvre Cp 11035)

c. 560-540 BCE black-figure neck-amphora (Louvre E 812) - Another anomalous version in which the hero is shown using a sword to attack the lion.

c. 510-500 BCE black-figure hydria fragment (Louvre Cp 10692)

c. 540 BCE black-figure amphora (Louvre F 1)

The subject of Herakles and the Nemean lion certainly does seem to be a favorite for black-figure vase painters in the second half of the 6th century BCE. Depictions of Herakles in Archaic (e.g., black-figure) tend to emphasize the muscular build of the hero, and the heroic exploit itself is a testament to great strength: the hero overpowers the savage beast without a weapon, "on its own terms," one might say. This emphasis on heroic strength and overpowering the beastial opponent without the tools of civilization (e.g., sword, spear, etc.) is famously repeated in the medieval Germanic poem Beowulf in which the titular hero slays the monstrous beast, Grendal, without the aid of sword, spear, or tool of humankind.

Herakles' second labor follows the same pattern as the first. Eurystheus orders the hero "to kill the Lernaian Hydra, which had been raised in the swamp of Lerna and was making forays onto the plain ans wreaking havoc on both the livestock and the land."[5] The hero slays a savage foe that acts as an impediment to civilized cultivation of the land. Or in another light, the hero acts as an agent that asserts human dominance over the natural world.[6]

Once again, the exploit highlighted the hero's martial prowess or athletic excellence. However, the hydra was not defeated by brawn alone. Cauterizing the stumps so that new heads would not sprout after each head was removed also suggests that Herakles could adapt and think on his feet. This may also have been the first time Athena's connection as the "helper of heroes" impacted Herakles. In general, Athena gives aid to heroes in the form of divine knowledge. For example, she informs Perseus how to go about slaying Medusa (avoid eye contact, use the reflection in your shield); or she instructs Jason to affix his ship with a branch from the Dodona Tree on its bow so that it always finds its way. This form of help to heroes would make sense to any god, but it is particularly meaningful from Athena, because while Athena is a warrior god, she is also the Olympian goddess of Wisdom and craft.[7]

That every severed or destroyed hydra head was replaced by two more is a common enough association with the term "hydra" in modern parlance that the basic concept needs no extra framework within the ancient tale. What is sometimes forgotten, however, is that the hydra was not the only creature Herakles slew during the fight; he also slew a giant crab. And Eurystheus did not count the hydra among the ten labors that Herakles was bound to do in service to Eurystheus on account that he received direct aid from another person (his nephew Iolaos) to complete the task. The presence of Iolaos and the crab are not essential elements in existing depictions of the labor, but they are common, almost as common as the presence of Athena, who is often in attendance whenever anyone more than Herakles and his adversary are depicted. Therefore we can ascertain that their participation was at least an early insertion, if not part of the earliest telling.

Right: Caeretan black-figure hydria (c. 530-510 BCE). J. Paul Getty Museum 83.AE.346

Iolaos attacks a hydra head with a harpe knife (left). Herakles bludgeons another hydra head (right). Just out of view on the right, a crab attacks Herakles' backmost foot.

Left: Black-figure stem amphora (c. 550 BCE). Athens National Museum 12075

On the main frieze, Herakles is depicted killing the Lernaian Hydra with the aid of Iolaos. Athena and Hermes attend the fight. Hermes is the most common god after Athena to be depicted giving aid to Greek heroes.

A hind is a female deer (more commonly referred to as a doe in contemporary American English). Fauns are young deer and are very closely associated with Artemis. However, all wild life is loosely associated with Artemis as well. The Keryneian hind was a specific female deer that was sacred to Artemis. What's more, she was generally described (e.g., by Apollodorus) and depicted (in Greco-Roman art) as having antlers - gold antlers, according to Apollodorus. The presence of antlers presents a minor gender deliniation issue for those demanding biological realism in their myths, but there seemed to be little trouble accepting an otherwise standard woodland female deer with antlers. More pressing for Herakles was that the deer was sacred to Artemis and, therefore, could not be harmed lest Herakles suffer the wrath of the gods. In fact, most versions of the story emphasize the fact that Artemis was unwilling to allow Herakles to simply requisition her dearest deer (d'oh!). In Apollodorus' telling, Herakles negotiates directly with Artemis, backed by her twin Apollo, to show the deer to Eurystheus in Mycenae and then release it unharmed back into the forest. In most visual representations, the divinities of Artemis and/or Apollo are counterbalanced by the presence of Athena, who in some cases was said to have negotiated with her half-siblings on behalf of Herakles. The end result is the same: Herakles is allowed to "borrow" the hind for the purposes of the labor, but he returns it to the wild unharmed.

Detail of attic black-figure amphroa (c. 530-520 BCE). Louvre F 234

Herakles stuggles with Apollo over the Keryneian hind. Artemis looks on behind Apollo while Athena does the same behind Herakles.

Photo: Jastrow (2006)

Black-figure neck-amphora (c. 540-530 BCE). British Museum 1843, 1103.80

Herakles struggles with the Keryneian hind, apparently breaking off one of its antlers. Athena frames the scene on the left, showing support while Artemis looks on from the right.

Photo: ArchaiOptix / Wikimedia

Copyright: (CC BY-SA 4.0), background removed.

The Erymanthian boar is my favorite labor in the visual record. The labor itself is very straightforward, and Apollodorus dedicates all of about three sentences to the event. By contrast, his description of the labor is bisected by a story about Herakles inadvertently sparking a centauromachy (battle with centaurs), which he dedicates three times more text to. Regardless, the boar represents another threat to human civilization: "This beast was causing destruction in Psophis by making attacks from a mountain they called Erymanthos,"[8] hence the name "Erymanthian boar." What makes this labor stand out is the almost tongue-in-cheek iconography of Eurystheus jumping inside a submerged pithos (large storage jar) making a frightened warding gesture toward Herakles who dangles the wild beast (very much alive and kicking) on his shoulder. Comical as it is, the iconography serves a very real point: it highlights the cowardice of Eurystheus in juxtaposition to Herakles' courage and strength. Recall that Eurystheus sits on the throne that Zeus intended for Herakles. The following visual narratives drive home the idea that Herakles was supposed to embody the aristocratic ideal of the heroic warrior king, such as one finds cutting down enemy soldiers in swathes in the Iliad. Note Apollodorus covers the same thematic ground as the pithos incidents in the visual record with the very first labor. Apparently, even the dead Nemean lion was too scary for Eurystheus:

Terrified by Heracles' demonstration of manly courage, Eurystheus forbade Heracles from entering the city in the future and ordered him tod isplay his labors before the gates of the city. [9]

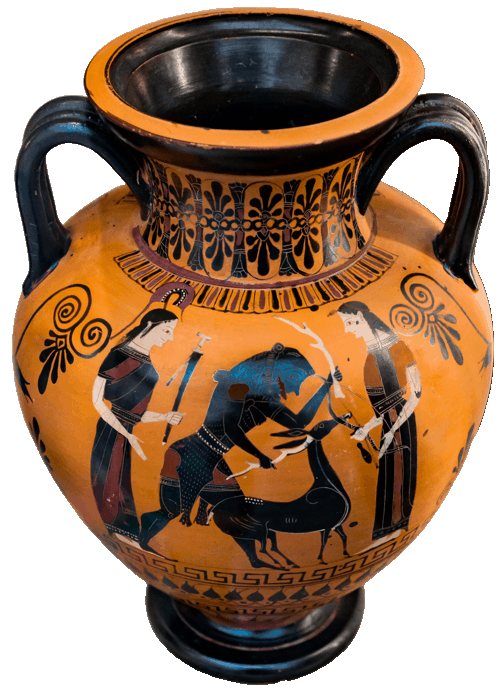

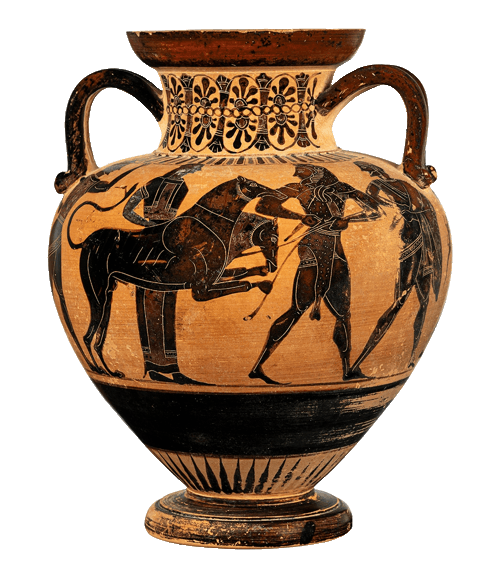

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to Leagros Group (c. 510 BCE). Getty 86.AE.83

Herakles, wearing lion-skin cloak and carrying his quiver, bow and sword, dangles the Erymanthian boar snout first over the head of a frightened Eurystheus who has taken refuge from the creature inside a submerged pithos. The scene is framed on the left by Athena (note that she stand behind the hero whom she supports) and on the right by an unidentified female (servant?).

Attic black-figure neck-amphora (6th century BCE). Met 06.1021.88

The central action of this scene and its iconography is virtually identical to the previous vase, but here, the scene is flanked by Athena on the right (flesh painted white is common for females in black-figure) and Iolaos on the left, holding Herakles' club and bow.

Very few representations of this labor survive in the visual record. It is somewhat anamalous among Herakles' exploits in that it does not involve monster slaying or a very meaningful juxtaposition between civilized and savage values. In Apollodorus' version of the story, Herakles tricked Augeias into paying him to clean the dung from the pen or structure(s) in which Augeias kept his cattle if he could accomplish the task in one day. As with all the labors, however, Herakles was ordered to perform the labor in accordance with his deal with Eurystheus. Thus, while Augeias was unable to win a civil suit against Herakles - there hero did everything he agreed with Augeias to do in order to receive payment - Eurystheus learned about it and discounted the labor. This was the second and last of Herakles' labors that was discounted by Eurystheus, and it is the reason that the final count of the labors is 12 instead of the 10 dictated by the orders of the Pythia.

The deed itself continues to emphasize Herakles' superhuman strength as he diverts the course of two rivers to clean the pen area of the cattle that was covered in dung. Also, like the Lernean hydra episode, highlights a high degree of tactical acumen. In other words, brute strength/athletic prowess was absolutely necessary for both labors, but the ingenuity to apply that strength effectively represent virtues of a leader and ideas one might expect to have come to a hero championed by Athena (goddess of wisdom), but they are not always associated with Herakles, who was also known for a quick temper and acting before thinking (consider the episode with Linos in Herakles' teenage years).

Marble bas-relief, Temple of Zeus at Olympia (c. 470-457 BCE).

Only fragments remain, and metopes are notoriously restrictive in how many figures can be portrayed in the small box. Here, we see Athena directing Herakles where to thrust his shovel(?) in order to divert one of the rivers that will rush through the cattle pen and flush out the dung.

Photo: Egisto Sani (CC BY-NC-SA-20)

The Stymphalian birds labor follows the typical monster slaying template of the hero confronting an enemy from wild or savage nature that prevents humans from exploiting the natural resources of a given area. In that sense, this labor is particularly reminiscent of the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh's conquest over Humbaba, the guardian of the Cedar forest. Gilgamesh led an expedition of men from his city of Uruk into the forest, which belonged to the gods, and he slew its guardian, Humbaba, variously described as a giant or a dragon-like creature. The men he brought with him felled many of the cedar trees and brought the valuable resource back with them to be used by Gilgamesh's people in Uruk.

For this labor, Herakles must drive away or slay the birds that inhabit the marsh near Stymphalos. In Apollodorus' version of the myth, the birds are more of a petty annoyance, and the marsh is not noted as valuable land. However, Pausanias describes a more nuanced tale:

There is a story current about the water of the Stymphalos, that at one time man-eating birds bred on it, which Herakles is said to have shot down. Peisander of Kamira, however, says that Herakles did not kill the birds, but drove them away with the noise of rattles.

The Arabian desert breeds among other wild creatures birds called Stymphalian, which are quite as savage against men as lions or leopards. These fly against those who come to hunt them, wounding and killing them with their beaks. All armour of bronze or iron that men wear is pierced by the birds; but if they weave a garment of thick cork, the beaks of the Stymphalian birds are caught in the cork garment, just as the wings of small birds stick in bird-lime. These birds are of the size of a crane, and are like the ibis, but their beaks are more powerful, and not crooked like that of the ibis. Whether the modern Arabian birds with the same name as the old Arkadian birds are also of the same breed, I do not know. But if there have been from all time Stymphalian birds, just as there have been hawks and eagles, I should call these birds of Arabian origin, and a section of them might have flown on some occasion to Arkadia and reached Stymphalos. Originally they would be called by the Arabians, not Stymphalian, but by another name. But the fame of Herakles, and the superiority of the Greek over the foreigner, has resulted in the birds of the Arabian desert being called Stymphalian even in modern times. In Stymphalos there is also an old sanctuary of Stymphalian Artemis, the image being of wood, for the most part gilded. Near the roof of the temple have been carved, among other things, the Stymphalian birds. [10]

The birds became a real threat to human habitation and exploitation of a lake and its resources in Pausanias' retelling. However, all textual sources agree on the manner in which Herakles dealt with the birds. He was unable to effectually target them with bow and arrow while they took cover in the trees, so he shocked them out of their roosts with loud noise (either drums or some sort of rattling device). When the birds took flight, Herakles was able to pick them off with his poisoned arrows. Those that he did not slay were driven away from the land, and the lake was made safe for human fishermen to exploit. The extended quote from Pausanias also highlights the ethnocentrism inherent in many of the heroic myths: "the fame of Herakles, and the superiority of the Greek over the [barbarian], has resulted in the birds of the Arabian desert being called Stymphalian even in modern times." Just as heroes slaying monsters represents the conquest of the civilization over savage nature, so too do many of the myths symbolically represent the superiority of the (civilized) Greek over the (savage) barbarian and the (rational) male over the (irrational or untamed) female. Pausanias applies this rationalization for the naming of man-killing birds on the Arabian peninsula as "Stymphalian birds," given deference to the Greek point of view over the barbarian other.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) background removed.

Attic black-figure amphora attributed to Group E from Vulci (c. 540 BCE). British Museum 1843,1102.40.

Herakles slaying the Stymphalian birds with sling (not arrows dipped in the blood of the hydra). Heracles wears a short purple chiton with lion's skin over head and body, quiver slung at back; there are 16 total birds, five have not yet taken flight while the rest fly around in confusion.

The labor involving the Cretan bull is almost a carbon copy of the Eurymanthian boar: Eurystheus orders Herakles to retrieve a beast, alive, and bring it back to show Eurystheus. No small amount of students and commentators have questioned, at this point, why Eurystheus continues to require Herakles to bring terrifying creatures into his presence since it will only cause him to jump into a pithos and look the fool? There are two answers to such questions, but neither is particularly necessary:

However, neither of these explanations are even necessary for a student of Greek myth. The fact of the matter is that the Twelve Labors, like the Epic of Gilgamesh millennia earlier, represent the culmination of many different individual myths/exploits told separately then later revised and adjusted to fit into a more streamlined and cohesive larger story. This is where the differences between textual sources and surviving visual representations of the myths can help bridge this intellectual impasse. The visual representations of many exploits by Herakles, Theseus, and Perseus predate most of the surviving literary sources for their most popular exploits. While there are a wealth of red-figure vase paintings narrating the exploits of our heroes from the Classical and Hellenistic periods, there are also many from the Archaic period, particularly the 6th century, but also some important artwork from the 7th century, and some of these vase paintings are not sourced from Attica. This is particularly important because many of these Archaic and non-Attic vases present us with clear variations to the literary versions that survive from the Classical and later periods of Greek history. In short, there is a tendancy to treat (e.g.) the Library of Apollodorus as the definitive source on Herakles and his twelve labors when, in fact, it is just one of many versions of the myth. It just so happens to be the most accessible of the surviving literary versions.

The final lines of Apollodorus' version of the Cretan bull episode are interesting:

[Herakles] captured it, carried it back, and showed it to Eurystheus. Afterward, he let it go free, and it wandered to Sparta and all of Arcadi, and, crossing the Isthmos, it came to Marathon in Attica, where it plagued the locals.

Although this labor follows the basic pattern of heroic monster slaying, Herakles does not actually slay this beast. In fact, he lets it go, and it turns into a problem for civilization that it did not seem to be while on Crete. The actual slaying of the beast would fall on the shoulders of Theseus, the "Athenian Herakles."

Apollodorus is uncertain as to the identity of the Cretan bull, whether it was the bull that carried Europa to Crete from Tyre or the pristine white bull that Poseidon created for Minos to sacrifice but that the Cretan king chose to keep for his own herd. The bull that carried Europa was often considered to be Zeus himself, transformed into a bull as he was famous for his metamorphoses while wooing mortal lovers. Thus, identifying the bull in Herakles' seventh labor as the white bull created by Poseidon makes for the more narratively consistent choice. Here again, however, we run the risk of forcing consistency between multiple myths that were probably not conceived as one contiguous narrative when they were first told.

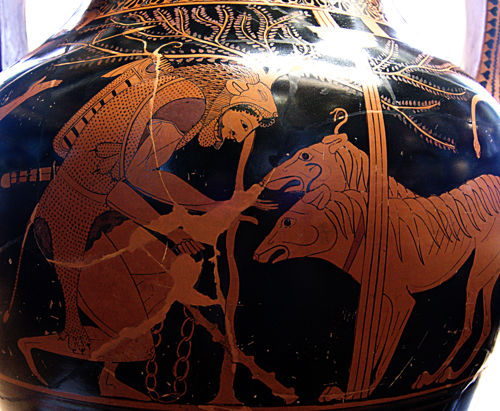

Attic black-figure oinochoe (c. late 6th/early 5th century BCE). Met 2011.604.3.777

Herakles capturing the Cretan bull; hanging in the field, at the left, is Herakles' chlamys; above the hindquarters of the bull, Herakles' bow and quiver.

Differentiating Herakles from Theseus is difficult because they are often depicted without their primary attributes. Fortunately, the bow and quiver above the scene are enough to identify this as Herakles.

Attic black-figure neck-amphora (c. 520-510 BCE). Met 41.162.193

Herakles, having forced the Cretan bull down on one knee, tightens a rope that binds the animal around its horns, left hind leg, and testicles.

The eighth labor required Herakles to bring the man-eating Mares (female horses) of Diomedes (a Thracian king) before Eurystheus in Mycenae. Initially, this looks like another version of the Erymanthian boar, "catch and release" quests. However, the themes underlying the labor are less a showcase for heroic strength or courage and more geared toward politics or ethnocentrism. These themes rise in prominence once Herakles' labors take him outside of the traditionally Greek territories.

As Apollodorus tells the story, Diomedes was "king of the Bistones, a very warlkike Thracian tribe, and owned man-eating mares." Thracians were not Greek. They were considered barbaroi ("barbarians," non-Greeks), along with all the negative and savage connotations that the term barbarian carries in modern English. Their description as "warlike" is akin to ideas of satyrs being lushes who did not control their carnal impulses or centaurs who turned violent when they failed to practice moderation (sparking the battle of Lapiths and Centaurs). The savagery of maintaining man-eating horses hardly needs characterization, but if that were not savage enough in itself, feeding humans to his horses wasn't simply a violation of natural (and civilzed!) order, but it was a mediated form of cannibalism. Diomedes did not consume the flesh of his enemies himself, but he does do so by dostorting the diet of his horses (horses are naturally herbivores, in case that wasn't clear!). There's even a hint of gender politics in the myth insofar as the horses are distinctly female. Although a minor observation in this labor, it plants the seed for a much larger role the following labor (belt of Hippolyta).

The resolution of the labor varies slightly between Apollodorus and other surviving sources, but the civilization message and the role of justice is the same. In Apollodorus, Herakles simply slays Diomedes while the Thracian led his men against the hero:

Heracles fought the Bistones, and by killing Diomedes he forced the rest to flee. He founded a city, Abdera, by the tomb of the slain Abderos, and then took the mares and gave them to Eurystheus. Eurystheus released them, and they went to the mountain called Olympos, where they were destroyed by the wild animals.

Thus, the mares, abominations of the natural order (justice), were done away with. Diodorus Diculus tells more overtly moral story:

The feeding-troughs of those horses were of brass because the steeds were so savage, and they were fastened by iron chains because of their strength, and the food they ate was not the natural produce of the soil but they tore apart the limbs of strangers and so got their food from the ill lot of hapless men. Herakles, in order to control them, threw to them their master Diomedes, and when he had satisfied the hunger of the animals by means of the flesh of the man who had taught them to violate human law in this fashion, he had them under his control.

And when the horses were brought to Eurystheus he consecrated them to Hera, and in fact their breed continued down to the reign of Alexandros of Makedon [i.e. the historic Alexander the Great]. [12] (emphasis added)

Diodorus overtly states the savagery of the mares; he highlights their abnormal strength, and the abhorrent nature of Diomedes' actions and his creations is ratcheted up by feeding travelers/strangers to his mares. In other words, Diomedes violated the divine law of xenia (hospitality, guest-friendship), sacred to Zeus himself (Zeus Xenios). Herakles then punished the evil-doer by way of an eye-for-an-eye justice; he fed Diomedes to his own horses. The early labors of Thesesus are virtual carbon copies of Diodorus' version of this labor. Ultimately, the themes of the myth between Apollodorus and Diodorus are the same, but Diodorus' version pushes them more overtly. Diomedes was a barbarian who perverted the natural order (horses eating humans) and the justice of Zeus (violating xenia). He was therefore punished for his hubris ("outrage"), thus affirming the ethnocentric world view espoused in the myth.

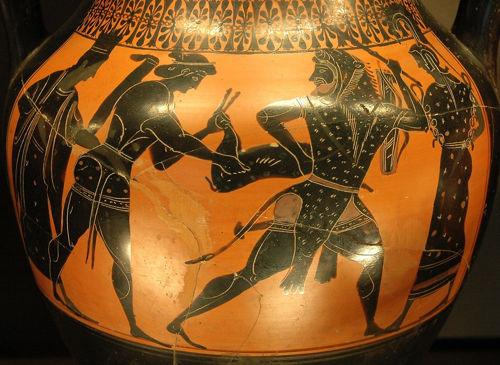

Attic black-figure kylix (c. 530-520 BCE).

Hermitage ГР-28190

"On the inside of the bowl is Heracles taming a mare of Diomedes. King of Thrace, Diomedes fed his mares on the flesh of strangers who entered his kingdom. Heracles overcame Diomedes and threw him to his own horses, which he then tamed." Look closely to see the remnants of an arm in the horse's mouth.

Click here to view the vase on the Museum's web site.

Marble frieze from Delphi (c. 67 CE).

"Slabs from the relief of the Frieze that adorned the proscenium of the theatre at Delphi.Probably they were created for Nero‘s visit to Delphi in 67 AD." (Rosina Colonia, The Archaeological Museum of Delphi).

Photo: Egisto Sani (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The belt of Hippolyte (also called the belt of Ares) was gifted to the Amazon queen by the Olympian god of war "as a symbol of her preeminence over all the Amazons."[13] Eurystheus wanted the belt as a gift for his daughter, another subtle shot at the unfit nature of Eurystheus as king of Mycenae to tempt war with the Amazons over a frivolous prize. According to Apollodorus, Herakles slew Hippolyte because of a deception by Hera, and then he had to battle his way through the other Amazons then brought the belt back to Eurystheus (skipping a famous side quest at Troy). However, Herakles was not always depicted as a lone warrior against the Amazons. Famously, Theseus was said to have accompanied him to Asia and came away with a new bride.

The major themes of this labor are more heavy-handed variations on those of the previous labor: the superiority of patriarchal Greek civilization in contrast to a nation of barbarian women who pervert the civilized order by partaking in the activities of men. Herakles' defeat of the Amazons asserts this world view. Amazonomachy means "war with the Amazons." It usually refers to Herakles' battle with them in his ninth labor, but there were others, the most famous of which being (you guessed it) between Theseus and the Amazons in Attica (sometimes called the "Attic War").

Along with the Giantomachy ("war between Olympians and Giants") and Centauromachy ("war with Centaurs"), the Amazonomachy was very popular in Greek art for symbolizing civilized Greeks conquering savage barbarians. Thus, there are many representations of Herakles battling Amazons, particularly on vases and friezes adorning civic buildings (e.g., temples), but by the fifth century, the Centauromachy scenes focused on Theseus as so much of the art was Athens-centric.

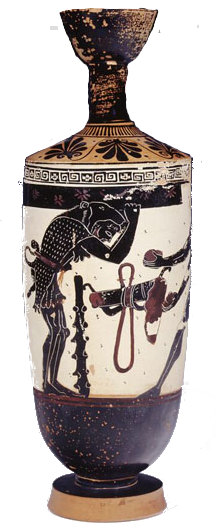

Attic black-figure lekythos by the Himon painter (c. 525-475 BCE).

"Herakles is depicted on this black-figure lekythos with his usual attributes, the lion skin and the club, which he holds in his right hand, and a quiver" (Walters). The female's flesh is painted white, and the artist has chosen to depict the Amazon in hoplite armor rather than the Phrygian cap and Persian archer garb often used to delineate them from Greeks.

Collection of Attic black-figure lekythoi from the National Archaeological Museum at Athens.

The top two vases clearly depict Herakles slaying an Amazon warrior. Both Amazons are dressed as hoplites; female flesh is painted white on the leftmost vase.

The other vases show Amazons, identifieable by their Phrygian caps and close-fit, eastern archer clothing.

Photo: Gary Todd.

Attic red-figure volute-krater attributed to Euphronios (c. 510-500 BCE). Arezzo 1465

Herakles and Telamon fight the Amazons on the belly of the vase (names inscribed). The Amazons are depicted as both hoplites and archers. Telamon is the father of Ajax from the Iliad. Herakles' adventures took place the generation before the Trojan War.

Photo: ArchaiOptix

Copyright: (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The cattle of Geryon is one of the more elaborately detailed labors in Apollodorus (skipping minor exploits), and it is filled with a series of events. However, the event that appears in the visual record most often and that for which the labor is named is Herakles' battle with Geryon, the three-bodied giant descended from Medusa and the Oceanid (nymph) Callirhoe. He dwelt on a far-off island named Erytheia, near the end of the earth (Apollodorus describes it as "an island lying near Oceanos"). It was one of the three Hesperides. The Hesperides were goddesses of the setting sun, and their islands are so named for the location on the western edge of the world. Furthermore, Hades kept his cattle on the same island. Herakles' labors have taken him farther and farther afield, into barbarian territories. This trek pushes him not only to the edge of civilization, but the edge of the mortal realm.

The theft of cattle is a popular device in Greek myth, particularly cattle associated with the Sun. In the Odyssey, Odysseus and his men illicitly slaughter and eat cattle belonging to Hyperion (or Helios, Homer seems to conflate the pair).[14] In the Homeric hymn to Hermes, the infant Hermes steals the cattle of Apollo (another Sun god). The cattle of Geryon reside on an island associated with Sun deities.

The cattle themselves are tended by the shepherd Eurytion and guarded by the two-headed hound Orthos. Orthos is the offspring of the monstrous Typhon and Echidna, and brother to Kerberos, the three-headed watchdog of Hades. Herakles must slay Orthos, Eurytion, and Geryon in turn before he can confiscate the cattle and drive them, after a series of setbacks, to Mycenae where Eurystheus will sacrifice them to Hera.

This labor, then, hits many of the same thematic notes that are regularly associated with Herakles, mainly his great strength and courage in defeating monstrous offspring of enemies of civilization (offspring of Echidna, Typhon, Medusa). However, the extent to which this exploit takes Herakles away from not only his home, but the known world, is important. In order to reach the island, Herakles first proves his courage to Helios, who gifts him a golden cup which he must use to sail to, and back from, the island. This cup is another "level-up" token that the hero acquires to complete his quest, albeit a temporary one (vis-a-vis the lionskin or hydra-blooded arrows). In these final three labors, Herakles pushes and, ultimately, exceeds the bounds of the mortal realm. These events foreshadow the hero's eventual apotheosis (deification) and fulfill the Pythia's prophecy that Herakles will earn immortality after serving Eurystheus.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol / Wikimedia, background removed.

Click here for a detailed drawing of the entire vase in high resolution from The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Download the .TIF file.

Attic red-figure kylix by Euphronios (c. 510-500 BCE). Munich 2620.

Herakles battles Geryon with club and bow extended. One of Geryon's three bodies slumps backward with an arrow prodruding from his eye. The two-headed hound, Orthos lies dead between the two combatants with an arrow wound. Athena stands behind Herakles looking back to Iolaos (out of image) behind her. Around the rest of the cup, Eurytion, the herdsman, lies wounded, and named warriors are depicted leading the cattle away.

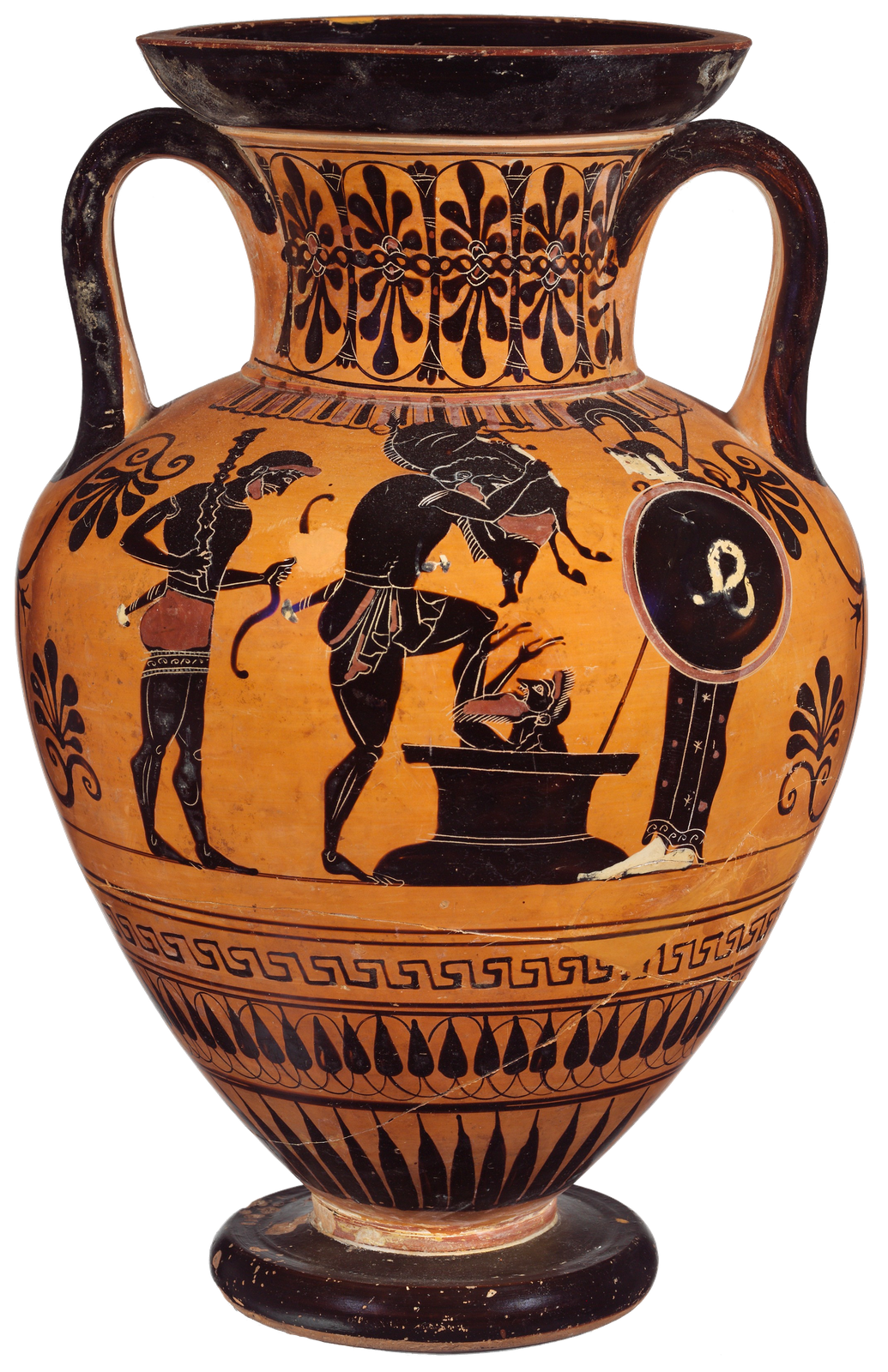

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to Princeton Group (c. 540-530 BCE). Met 2010.147.

Herakles draws his bow to on one side of the vase to fire at the three-bodied giant Geryon on the other side of the vase. Note one of Geryon's bodies is hanging down and facing backward. One of Herakles' arrows has already struck home. As is common, Herakles is depicted wearing his signature lionskin cloak.

Originally, the Hesperides lived on their islands, one of which was home to Geryon and his cattle from the previous labor, located somewhere in the great river Okeanos (i.e., ocean that flows around the outside of the world). Later traditions place the islands somewhere off the southern coast of Spain, but at that time (e.g., in Apollodorus), the Hesperides no longer live there. At least for Apollodorus, they reside atop the Mount Atlas in the Hyperboreans. This would place them at the northern edge of the world rather than the western one - Hyperboreans meaning, according to Pausanius, "The land of the Hperboreans, men living beyond the home of Boreas," the god of the northern wind. However, Apollodorus also mentions that they were not in Libya (northern Africa near the southern edge of the world), which was a popular belief. Indeed, the trek Herakles makes getting to (or near) the sacred grove of the Hesperides is mind boggling: it takes him through northern Africa back to the Caucassus on the eastern edge of the world (past the Black Sea), to Atlas "in the land of they Hyperboreans," presumably on the northern edge of the world.

Herakles' journey across the northern regions of Africa, into northeast Asia, and then to a nebulous northern European home of the Hyperboreans provided fertile soil for many of the hero's more popular side exploits. They make for a minor "odessey" in their own right. Thus, there are quite a few side quests or minor exploits along the way. Of the events directly related to the apples, however, there are 3:

Bearing the sky on his shoulders is certainly a significant feat of strength, and it is perhaps the most memorable deed Herakles performed during this labor. Yet, he also outsmarted a god (Atlas), freed a god (Prometheus), and successfully wrestled a god into submission (Nereus). And then, of course, there is the aforementioned extension of his wanderings to the very edge of the world. This event always brings to mind two mental images. One is the cover of Shel Silverstein's Where the Sidewalk Ends. The other is Odysseus sitting at the edge of the earth in front of a ditch waiting for psuches of the dead to rise up and speak with him.

Oopsy! Looks like this vase is in the MFA, Boston, and they don't license public display. I'm not sure this counts as fair use. /sadface. Please click the link:

Attic red-figure pelike by the Lykaon Painter (c. 440 BCE).

Right: Attic Black-figure (white ground) lekythos attributed to the Athena Painter (c. 525-475 BCE). Athens 1131

Atlas recovers the golden apples of the Hesperides for Herakles. An apple extended from Atlas' hand is just visible.

Above: Boeotian Black-figure kylix (late 6th to early 5th century).

Louvre MNE 1309.

Photo: Egisto Sani. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Herakles prepares to free Prometheus as an eagle flies-in from the right.

Attic black-figure neck-amphorain the manner of the Antimenes Painter (c. 520-510 BCE). MKG 1983.274a-b.

Herakles wrestles with and subdues the sea god Nereus (The Old Man of the Sea). Nereus told Herakles how he could reach/retrieve the apples of the Hesperides

Attic red-figure kylix (c. 500 BCE). Athens 1666.

Herakles wrestles with the giant Antaios in Libya. This encounter took place during Herakles' trek across northern Africa after speaking with Nereus. Both figures are named on the vase.

Photo: Jerónimo Roure Pérez (CC BY-SA 4.0), background removed.

The twelfth and final labor is a fitting endpoint for the greatest of heroes in the klea andron. Once again, this exploit showcases Herakles' super strength in subduing Kerberos (brother to Orthos and descendant of Typhon), and it pushes even further beyond the realm of humans than any other labor. The metaphorical significance of this, however, is greater than any other labor and, in fact, places Herakles in a rarefied air even amongst the other heroes of the Heroic Age.

Kerberos is the watchdog of Hades. Humans are mortal; we die and do not come back. The symbolic power of Kerberos as the watchdog of Hades is not to protect his master's realm from intrusion (who wants to die and live amongst shades of men? - see Odysseus' discussion with shades in the gloom of Hades during the Odyssey). Kerberos prevents shades from leaving. As the saying saying goes, it isn't difficult to go to the underworld; the problem is getting back out. In fact, this very point is pressed home during Herakles labor when he encounters his friends Theseus and Peirithoös trapped in the underworld, having traveled there while still alive. By overpowering Kerberos, literally mastering the dog, and returning to the living world, Herakles metaphorically conquers death, and this metaphor (or partial metaphor as he actually does overpower Kerberos in some versions) becomes fact in his apotheosis and ascent to Olympos. Again, Herakles' victory and mastery over Kerberos symbolizes (or foreshadows) the hero's victory over his own mortality. He will not simply gain the kleos aphthiton heroes strive for in the songs of men, but he will achieve literal immortality as a god on Olympos.

This labor also provides Greek visual artists one more opportunity to contrast the cowardly nature of Eurystheus with the aristocratic strength and courage of Herakles by showing the king of Mycenae cowering in a pithos at the sight of Kerberos in his palace.

Caerean black-figure hydria by the Eagle Painter (c. 525 BCE). Louvre E 701.

Herakles presents Kerberos to Eurystheus who hides from the beast inside a large pithos.

Each of Kerberos' heads is painted a different colors with jaws open and covered by snakes. Herakles controls the dog with a leash and club, possibly carrying it or restraining it as it tries to lash out.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol

Attic bilingual amphora (detail of red-figure side) by Andokides Painter (c. 530-520 BCE). Louvre F 204.

Herakles kneels down before Kerberos with chainlink leash in one hand, the other reaching out toward the dog.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to the Painter of the Amphora Vatican 365 (c. 540-530 BCE). MKG 1984.429.

Herakles leads Kerberos from the underworld on the order of Eurystheus of Mycenae. The Heracles, walking to the right, is dressed in a short robe and recognizable by his lion's fur. He holds Kerberos on his leash and looks around him. Three figures follow the events: Hermes to the left (partially pictured), a woman in peplos (likely Persephone). To the right stands a male figure with a short robe and coat (likely Hades).

Attic black-figure column krater (c. 550-530 BCE).

Herakles leading Kerberos on a leash. Athena and Hermes precede the hero.

Photo: ArchaiOptix (CC BY-SA 4.0).

[1] Emma Stafford. Herakles. Routledge (2012).

[2] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans.). Hackett (2007).

[3] Emma Stafford. Herakles. Routledge (2012).

[4] ibid.

[5] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans.). Hackett (2007).

[6] The definition of a tool: "an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment." In terms of the civilized and savage dichotomy that permeates so much of the mythological imagination, a tool is a product designed to manipulate or assert control over nature.

[7] Athena was born "without a mother" from the head of Zeus. However, she was the product of the union between Zeus and Mētis ("cunning intelligence"). Zeus swallowed Mētis while she was pregnant with Athena. Thus, Athena as the helper of heroes is doubly significant: she is a goddess undefeated in battle who supports the greatest warriors of Greek myth, and she is also the progeny of both Zeus (who communes with the Fates) and Cunning Intelligence.

[8] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans.). Hackett (2007).

[9] ibid.

[10] Description of Greece, Volume I: Books 1-2 (Attica and Corinth). Loeb Classical Library 93. Pausanias. Trans. W. H. S. Jones. Harvard UP (1918).

[11] Apollodorus regularly and openly recalls variant versions of many myths, and he never (or exceedingly rarely) states the source of the narratives that he presents as the dominant iterations.

[12] Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 15. 3 - 4 (trans. Oldfather). Theoi.com.

[13] Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology. R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma (trans.). Hackett (2007).

[14] In Hesiod's Theogony, Hyperion is the titan whose name means "Heavenly Light," and his son, Helios, is the Sun or the god who drags the Sun across the sky.