Book 22 is dominated by the confrontation between Hector and Achilles that the poem has built toward since Achilles withdrew from the Greek army in Book 1. The interaction between the greatest heroes of their respective armies is, in many ways, a climax to the major themes we have analyzed throughout the Iliad: the relationship between pity and rage and their impact on civilized and savage action; the concept of heroic honor and its relation to the community; and the relationships between the beautiful death, burial, and immortality. These themes are complex and interrelated and, as we shall see, they are prominent in the Book 22. In this chapter, we will focus on Hector’s decision to remain on the battlefield or retreat behind the walls of Troy and the climactic battle between Hector and Achilles.

Priam pleas with Hector to retreat behind the walls of Troy rather than face Achilles in single combat. His rhetoric details the beauty of heroic death in contrast to the horror of growing old and dying unburied – both of which are “ugly deaths.” Perhaps most important in Priam’s entreaty is its emphasis on Hector as steward and protector of the Trojan community. Let us examine Priam’s plea:

“Hector, my boy, you can’t face Achilles

Alone like that, without any support –

You’ll go down in a minute. He’s too much

For you, son, he won’t stop at anything!” (45-8)

Achilles “won’t stop at anything.” At face value, Achilles will not be deterred from his goal of slaying Hector, but the line also hints at the savagery of the Greek warrior. Achilles is driven mad by rage, and he no longer acts according to the unspoken rules of chivalrous combat through which Greek and Trojan warriors derive honor (social status).

Priam continues by elaborating on the loss of his other sons versus the value of Hector’s life:

“So many fine sons [Achilles has] taken from me,

Killed or sold them as slaves in the islands.

two of them now, Lycaon and Polydorus,

I can’t see with the Trojans safe in town,

Laothoë’s boys. If the Greeks have them

We’ll ransom them with the gold and silver

Old Altes gave us. But if they’re dead

And gone down to Hades, there will be grief

For myself and the mother who bore them.

The rest of the people won’t mourn so much

Unless you go down at Achilles’ hands.

So come inside the wall, my boy.

Live to save the men and women of Troy.

Don’t just hand Achilles the glory

And throw your life away.” (52-66)

Lycaon and Polydorus were beloved by Priam and Laothoë, their parents. As such, their family will mourn them. Hector, however, is a different story. “The rest of the people,” the community or Trojan people, won’t mourn Lycaon or Polydorus with the intensity of their parents. Hector, however, is more than a prince. He is the champion of Troy. His prowess and leadership in battle are the cornerstone of Trojan defenses against the Greek onslaught. Hector is not simply another son of Priam. He is the best hope for Troy to survive this war. Priam states, in no uncertain terms, that Hector is no match for Achilles in a one-on-one contest and that the community needs him to survive.

Priam then appeals to Hector on an emotional level, asking for pity, as he foreshadows the very events that will occur after the Iliad when Troy is sacked:

“Show some pity for me

Before I go out of my mind with grief

And Zeus finally destroys me in my old age,

After I have seen all the horrors of war –

My sons butchered, my daughters dragged off,

Raped, bedchambers plundered, infants

Dashed to the ground in this terrible war,

My sons’ wives abused by murderous Greeks.” (66-73)

Finally, Priam compares the glory of a warrior’s beautiful death to the horror of old age and disfigurement of one’s corpse:

“And one day some Greek soldier will stick me

With cold bronze and draw the life from my limbs

And the dogs that I fed at my table,

My watchdogs, will drag me outside and eat

My flesh raw, crouched in my doorway, lapping

My blood.

When a young man is killed in war,

Even though his body is slashed with bronze,

He lies there, beautiful in death, noble.

But when the dogs maraud an old man’s head,

Griming his white hair and beard and private parts,

There’s no human fate more pitiable.” (74-85)

The contrast between civilized and savage is palpable, and the two are separated by a knife’s edge. Priam asserts that there is beauty and nobility in dying young in battle, despite the scars one may accrue in the deed that brings about the warrior’s demise. This beauty is twofold: firstly, the warrior dies in the noble act of service to his community. He chooses to fight and die rather than retreat like a coward. Perhaps the longest-lived definition of a hero is one who willingly runs toward the dangerous or frightening object that everyone else runs away from. Yet these concepts account only for the “nobility” of such a warrior’s death. Nobility is a form of cultural coinage. The warrior who sacrifices his life is rewarded with honor, including the view of his action and character as “noble.” However, Priam also emphasizes the beauty of the deed.

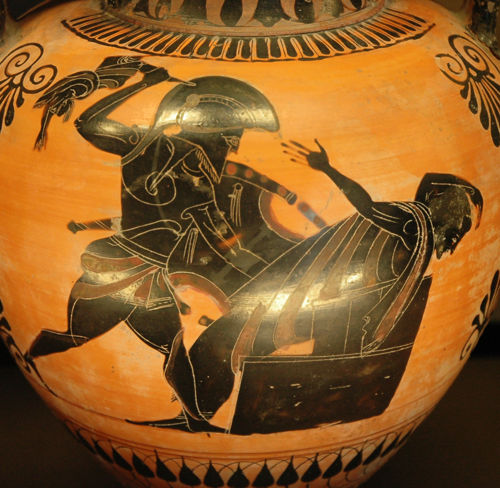

Attic black-figure amphora from Vulci (c. 520-510 BCE). Louvre F 222.

Priam killed by Neoptolemos, son of Achilles. The savagery of the sack of Troy was an infamous event in Greek myth. Perhaps no better example of the "ugly death" that Priam describes in Book 22 can be articulated than the king being bludgeoned to death with the corpse of his own grandchild (Astyanax).

The most articulate and complete surviving version of the Greek crimes during the sack of Troy is depicted on an Attic red-figure hydria by the Kleophrades Painter (c.490-470 BCE). Unfortunately, I could not find a version of it with necessary copyright releases.

It depics the death of Priam seated at the altar of Zeus with his dead grandson sprawled across his lap; his daughter, Cassandra, in the process of being raped by Lesser Ajax as she clings to a statue of Athena; and Aeneas escapes the carnage, leading his young son, Ascanius, by the hand and carrying his father, Anchises, on his back.

Photo: Jastrow (wikimedia)

Priam contrasts the old man who dies unburied, unmourned, and made into food for the dogs that would serve him in an ordered, civilized society, with that of a young man dying on the battlefield. In doing so, he alludes to the kleos (fame) of the beautiful death and the memory of eternal youth that accompanies it. In other words, to die young in battle is to circumvent the process of aging. The young hero dies while committing a noble act. He will never grow old in the memory of his people because he literally never grows old. Yet there exists the potential for a horrific rewriting of this kleos. Priam speaks of the dogs that molest an unburied corpse. This event is no doubt horrific to witness, but it is not exclusive to victims in old age. In Book 21, Lycaon experienced just such a fate. Rather than dying young and receiving honorable burial, the Trojan’s corpse was hurled into the river to be devoured by savage nature (the dogs in Priam’s plea). This is the “ugly death” that Achilles promised Trojans and the children of Priam in Book 21. It is the inverse and negation of the “beautiful” and “noble” death that warriors fight and die for throughout the poem and as Priam described it above. Priam’s words are doubly prophetic because his fate in myths of the sack of Troy are very similar to the horrific death he describes here as a future possibility. See the red-figure hydria (pictured above) as one of many depictions of the sack of Troy and ugly deaths visited upon the Trojans by the Greeks.

Priam’s plea was not enough:

And the old man pulled the white hair from his head,

But did not persuade Hector.

While Priam’s attempt to persuade Hector was split between emotional and logical appeals, the appeal to pity is the primary thrust of Hecuba’s plea to her son:

His mother then,

Wailing, sobbing, laid open her bosom

And holding out a breast spoke through her tears:

“Hector, my child, if ever I’ve soothed you

With this breast, remember it now, son, and

Have pity on me. Don’t pit yourself

Against that madman. Come inside the wall.

If Achilles kills you I will never

Get to mourn you laid out on a bier, O

My sweet blossom, nor will Andromache,

Your beautiful wife, but far from us both

Dogs will eat your body by the Greek ships.” (88-99)

Hecuba’s plea is that of a mother for her child. Indeed, her “wailing, sobbing,” and bearing out her breasts is reminiscent of Achilles’ reaction, and that of his slave women, to Patroclus’ death. Like Priam before her, Hecuba begs Hector to retreat out of pity for the suffering his death will bring to her – not to the community. Also like Priam, she draws the distinction between Achilles and Hector as one would a man from a beast: Achilles is a “madman.” He is savage, unreasonable, and in his savagery, he will deny his vanquished foe even the smallest modicum of respect, a proper burial. We know this is true and have already seen it in Achilles’ treatment of Lycaon as well as his promise for similar treatment to other princes of Troy.

Hector refuses his mother’s entreaties just as he does his father’s. Hector’s rationale in coming to that decision that is both beautiful and tragic. It underscores the fundamental difference between Aeneas as the champion of Virgil’s Aeneid, and Hector as an ideal warrior in the Iliad.

Hector heard the pleas of his parents, and they gave him pause:

So Hector waited, leaning his polished shield

Against one of the towers in Troy’s bulging wall,

But his heart was troubled with brooding thoughts:

“Now what? If I take cover inside,

Polydamas will be the first to reproach me.

He begged me to lead the Trojans back

to the city on that black night when Achilles rose.

But I wouldn’t listen, and now I’ve destroyed

Half the army through my recklessness.

I can’t face the Trojan men and women now,

Can’t bear to hear some lesser man say,

‘Hector trusted his strength and lost the army.’

That’s what they’ll say. I’ll be much better off

Facing Achilles, either killing him

Or dying honorably before the city.” (111-125)

Hector’s concern, as he expresses it thus far, is that of personal honor. He was advised to retreat when Achilles first rejoined the Greek army, but he mistakenly chose to keep his armies on the battlefield, and that decision has proved disastrous. Should he now retreat, he fears being shamed by a lesser man (Polydamas or another Trojan). That is to say, it would be better for Hector’s personal honor or his self-image to fight and die against Achilles, proving his courage and earning a beautiful death.

The middle third of Hector’s deliberation considers the other possibility, suing for peace, bargaining with Achilles, retreating, in a sense, from a more powerful opponent:

“But what if I lay down all my weapons,

Bossed shield, heavy helmet, prop my spear

Against the wall, and go meet Achilles,

Promise him we’ll surrender Helen

And everything Paris brought back with her

In his ships’ holds to Troy – that was the beginning

Of this war – give all of it back

To the sons of Atreus and divide

Everything else in the town with the Greeks,

And swear a great oath not to hold

Anything back, but share it all equally,

All the treasure in Troy’s citadel.” (126-37)

It’s unclear if Hector’s ruminations on returning Helen are out of self-preservation alone or a larger interest in restoring order and justice. After all, Paris violated xenia in the first place with the rape of Helen that ignited the war, and again, he was guaranteed to lose his duel with Menalaus in Book 3, which would have resulted in the same acts of restitution that Hector mulls over here. Hector’s considerations are plausible from both points of view: self-preservation and concern for justice. However, there is a greater structural purpose in Hector’s expression of such a reasoned path to peace between Greeks and Trojan, and that is to highlight the implacable savagery of Achilles in juxtaposition to reason:

“But why am I talking to myself like this?

I can’t go out there unarmed. Achilles

Will cut me down in cold blood if I take off

My armor and go out to meet him

Naked like a woman. This is no time

For talking, the way a boy and a girl

Whisper to each other from oak tree or rock,

A boy and a girl with all their sweet talk.

Better to lock up in mortal combat

As soon as possible and see to whom

God on Olympus grants the victory.” 138-48)

There will be no reasoning with Achilles. The example of Lycaon definitively proved this point in Book 21. Casting off his weapons and pleading with Achilles for mercy, to feel pity, was a lost cause for Hector’s half-brother, and Lycaon had a far stronger claim for mercy than Hector, for Lycaon could claim the bonds of xenia with Achilles. No. There can be no reasoned negotiations with Achilles. No white flags or suing for peace. Such things are the idle fancies of young lovers and children. Hector is a chivalrous warrior. He will fight and die with honor.

The core elements of Hector’s decision to face Achilles can be found in his reply to Andromache in Book 6, when she too begs him not to return to the battlefield: “My shame before the Trojans and their wives…would be too terrible if I hung back from battle like a coward. And my heart won’t let me. I have learned to be one of the best, to fight in Troy’s first ranks, defending my father’s honor and my own” (6.463-9). Hector has been raised his entire life to pursue honor through martial prowess on the battlefield and to avoid the shame of running away. If he were to retreat now, he would put himself in the loathed position of Paris in Book 3, a man whose very proximity was anathema to the rank and file Trojans: “[Paris] could barely stand as disdainful Trojans made room for him in the ranks, and Hector, seeing his brother tremble at [the sight of Menelaus], started in on him with abusive epithets” (3.41-44).

Hector is compelled by duty to lead Troy’s armies, but that duty is linked to the community through the proxy of individual honor, the same individual honor that both bound Achilles to fight for Agamemnon and then drove a rift between them. Achilles was shamed by Agamemnon. Worse, he was shamed inappropriately, having been stripped unjustly of his war prize. This blow to Achilles’ individual honor led him to remove himself from his position as bulwark of the army, champion of the community. His individual honor was more important than the health of his community (the army). Achilles is not unique in this regard. Honor, as we have previously discussed, is the cultural coinage that binds warriors to their respective communities. The fissure in this system is that honor is inherently focused on the individual rather than the community, and that is why Priam’s appeal to Hector fails.

The proposition Priam makes to Hector is clear: sacrifice your individual honor for the greater good of the community. It’s a perfectly logical line of reasoning, as we discussed above. Yet it asks Hector to forego everything he is, everything he thinks himself to be. His “heart won’t let” him retreat, he tells Andromache in Book 6. Hector has wholly internalized the values of a timorous Homeric society, and those values demand he pursue honor and avoid shame. Sarpedon’s speech in Book 12 crystalizes this point: standing to fight so at the risk of one’s own life only makes the honor greater; it offers the opportunity to immortalize himself in a beautiful death.

Hector is dutiful, but he is very much a product of his environment. Hector’s action in the Iliad is fundamentally different from Aeneas of Virgil’s Aeneid in regard to the egocentric nature of Homeric honor. The piety or “duty” to which Aeneas is bound throughout the Aeneid is always in service to 1) the gods, 2) family, 3) community, generally in that order. The family, in this schema, is a microcosm of the community; thus they can be viewed as one and the same. The implication of this is that honor is only honorable for Aeneas when it is bound to his duty to the community (filial piety). Aeneas’s greatest glory in the Aeneid comes as an extension of his familial and communal success, something for which he sacrifices the opportunities both a beautiful death in the sack of Troy (Aeneid Book 2) and individual happiness in his romance with Dido (Aeneid Book 4). The Homeric ideal, as we have seen, is different. Achilles is willing to throw the entire Greek expedition into chaos for the sake of his individual honor. This is Ajax’s true criticism of Achilles in Book 9. It is no surprise, then, that Hector is willing to weaken the Trojan community for the sake of his individual honor as well. The very nature of Homeric honor demands that they do so.

The confrontation between Achilles and Hector represents the climax of the poem and, also, that of the binary opposition between civilized and savage imagery that has dominated the Iliad. We start with the conversation before the two heroes do battle. Hector begins with an attempt to ensure that Achilles will engage in honorable combat and respect the dead:

“I’m not running any more, Achilles.

Three times around the city was enough.

I’ve got my nerve back. It’s me or you now.

But first we should wear a solemn oath.

With all the gods as witnesses, I swear:

If Zeus gives me the victory over you,

I will not dishonor your corpse, only

Strip the armor and give the body back

To the Greeks. Promise you’ll do the same.” (277-85)

Achilles’ reply highlights the contrast between civilized, honorable combat on the one hand, and the savage rage that dominates Achilles’ thumos on the other:

And Achilles, fixing his eyes on him:

“Don’t try to cut any deals with me, Hector.

Do lions make peace treaties with men?

Do wolves and lambs agree to get along?

No, they hate each other to the core,

And that’s how it is between you and me,

No talk of agreements until one of us

Falls and gluts Ares with his blood.

By God, you’d better remember everything

You ever knew about fighting with spears.

But you’re as good as dead. Pallas Athena

And my spear will make you pay in a lump

For the agony you’ve caused by killing my friends.” (287-98)

Achilles likens himself to a savage lion stalking a human. There are no peace treaties between wild beasts and human civilization. Treaties do not exist outside of civilization. What fuels Achilles, he says, is hate, a burning hatred. He then promises that Hector will pay an undetermined price. Achilles has used this imprecise language before. In Book 9, while refusing Agamemnon’s offer from Odysseus, Achilles said that there was no price Agamemnon could pay to regain Achilles’ service, “Not until he’s paid in full for all my grief” (9.400). What does it mean to “pay in full for [Achilles’] grief”? Similarly, death will not be enough to assuage Achilles’ anger with Hector. The agony Achilles speaks of is his own rather than that of Patroclus, who died an ideal Homeric death on the battlefield while accomplishing mighty deeds of valor. The proof of this nebulous price that Achilles requires as recompense for his suffering is clear in the verbal exchange between the two warriors while Hector lay dying:

“I beg you, Achilles, by your own soul

And by your parents, do not

Allow the dogs to mutilate my body

By the Greek ships. Accept the gold and bronze

Ransom my father and mother will give you

And send my body back home to be burned

In honor by the Trojans and their wives.”

And Achilles, fixing him with a stare:

“Don’t’ whine to me about my parents,

You dog! I wish my stomach would let me

Cut off your flesh in strips and eat it raw

For what you’ve done to me. There is no one

And no way to keep the dogs off your head,

Not even if they bring ten or twenty

Ransoms, pile them up here and promise more,

Not even if Dardanian Priam weighs your body

Out in gold, not even then will your mother

Ever get to mourn you laid out on a bier.

No, dogs and birds will eat every last scrap.”

Helmet shining, Hector spoke his last words:

“So this is Achilles. There was no way

To persuade you. Your heart is a lump

Of iron.” (375-97)

Attic red-figure volute krater by the Berlin Painter (c. 490-80 BCE). British Museum 1848,0801.1.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

"Achilles aggressively leans in for the kill with the support of Athena whose hand urges him forward. Contrastingly, Hector falls backward, his spear arm already extended while Achilles’ spear remains cocked and ready for the killing blow. Apollo’s demeanor is the opposite of Athena’s as he retreats away, abandoning the Trojan hero to his fate." [1] Image of the full vase at right shows the opposite side (Achilles battles Memnon, each hero supported by his goddess mother, Thetis and Eos respectively.

Hector’s plea to Achilles is an appeal to civilized values, including the one emotion that unerringly works toward civilized values in the poem, pity. First, Hector invokes the soul of Achilles and his parents. These ideas are tied to pity and will recur in Priam’s interaction with Achilles in Book 24. The invocation of Achilles’ soul is straightforward: Hector calls on Achilles to pity his fallen enemy because he, too, will die, and when he does so, he will want to be buried. Thus, Hector asks Achilles to feel the most basic kind of human pity, that for the mortality of the human condition and the fact that, if nothing else, they share the promise of death in common.

The invocation of Achilles’ parents is another appeal to pity, but rather than for Hector, it is intended for Priam and Hecuba. The idea that Achilles would care about the king and queen of the enemy city is, from a removed perspective, absurd. But it hits closer to home than one might initially think, and it’s the same argument Priam will use successfully in Book 24. Hector asks Achilles to think of the pain that his own death will bring to his parents and their inability to properly mourn him when he dies, as he knows he will die far away from home. We noted Achilles’ hyper-awareness of the human condition when he refused to spare (feel pity for!) Lycaon in Book 21. In this way, Achilles and Hector are, or should be, linked: Peleus will be as helpless to burn and bury the body of Achilles as Priam will of Hector, if Achilles refuses to ransom his vanquished foe’s body. Thus, Hector appeals to Achilles’ sense of pity twice over and is rebuffed on both accounts.

Achilles refuses Hector’s request. The request for ransom is not unusual. To ransom a living son would undoubtedly yield a greater reward than a dead one, but either way, the gold that Achilles would receive by ransoming Hector would serve as timē, a trophy to honor him and announce the greatness of his warrior prowess by the largess of the ransom he receives. However, Achilles cares little for timē since Agamemnon stripped him of his prize in Book 1. He cares even less since Hector killed Patroclus and donned Achilles’ armor in Book 16. The enticement of ransom should move Achilles, just as the appeals to pity should move him, but this scene has played out numerous times before in the poem, most notably in Book 9 with the embassy to Achilles, and in Book 21 with Lycaon’s claim of xenia. Achilles is simply not moved by ties to the community, by civilized values. The rage that seeped into his bones and made his eyes glow like white-hot flame in Book 19 still rules his heart, and there is no room for such things as pity.

Achilles’ reply to Hector is the pinnacle of savagery in the Iliad: “I wish my stomach would let me cut off your flesh in strips and eat it raw for what you’ve done to me.” Achilles would gladly cannibalize Hector, eating him raw like a lion hunting his prey on the savannah. That is, after all, what Achilles likened himself to at the beginning of their confrontation, a lion who does not make treaties with men. Achilles is determined to deny Hector burial, and he expresses this fact, again, in language eerily similar to his rejection of Agamemnon’s offer in Book 9: there is no sum of money in the world that can turn Achilles from his savage purpose. As was the case before, he swells with rage, and that rage, alone, guides his actions.

Hector confirms this analysis for us:

“So this is Achilles. There was no way

To persuade you. Your heart is a lump

Of iron.” (395-7)

The confrontation between Achilles and Hector in Book 22 is a tragic inversion of the meeting between Diomedes and Glaucus in Book 5. Two warriors meet on the battlefield to test the mettle of their opponents and, thus, themselves. They seek to “know” each other. Hector learns the measure of Achilles. He knows who he is, and that is a man driven mad, a man who, as Ajax said in Book 9, “has made his great heart savage. He is a cruel man…. [Achilles is] pitiless.” (9.647-52). Achilles cannot be reasoned with: “There was no way to persuade you”; persuasion requires reason, a logical appeal. Achilles lacks the basic human capacity to feel pity: “Your heart is a lump of iron”; emotional appeals to civilized action fall on deaf ears – or a closed heart! – as well.

Attic white-ground lekythos from Eretria (c. 490 BCE). Louvre CA 601. Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol (wikimedia)

Achilles drags the body of Hector behind his chariot. The small winged figure flying behind is the psuchē (soul, spirit) of Patroklos.

[1] Susan Woodford, in Trojan War in Ancient Art . Cornell UP, 1993.