Much of Book 23 is abridged in our edition of the text. The bulk of the full version narrates the funeral games that Achilles sponsors in commemoration of Patroclus’ funeral. Our version narrates the preparations for, and burial of, Patroclus. It is to these brief exchanges that we turn our attention in this essay.

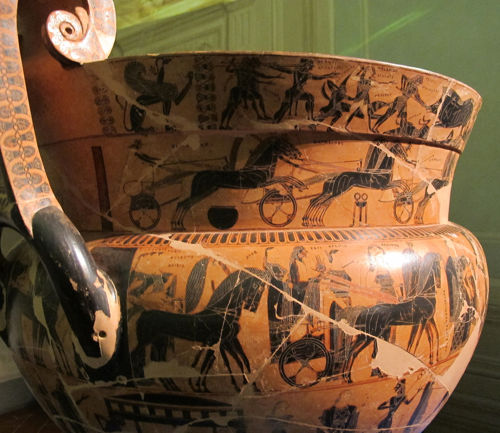

Photos: Sailko. License: (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Detail of the Francois Vase, a black-figure volute krater (c. 570 BCE) depicting the chariot race that was part of the funeral games for Patroclus as described in the Iliad. Note the tripod (lower left). Tripods were commonly used as trophies in the Greek world. Names of the heroes Diomedes and Agamemnon are visible. The full vase is shown from 2 different angles. Its friezes contain numerous scenes from Greek myth and are a treasure trove of Archaic mythological art. The vase was buried in an Etruscan tomb (Northern Italy). Significant Archaic and Greek art that survives today comes from Etruria (N. Italian) and Campania (S. Italian) settlements, including the only surviving frescos from the 5th century.

As we noted in previous chapters, human sacrifice is not uncommon in Greco-Roman myth, but it is very unusual as a historical practice.[1] The sacrifice of human victims, even in myth, is generally characterized as extreme or savage. The sacrifice of Iphigenia by Agamemnon is a popular example of this from an event occurring before the events of the Iliad in the Trojan cycle.

A 5th century tragedy by Euripides, entitled Iphigenia Among the Taurians, finds the maiden thrust into the role of priestess to Artemis for savage Taurians, ruled by King Thoas, who forces her to ritually sacrifice foreigners unfortunate enough to wander into his territory. This violation of xenia is tied to the horror of human sacrifice, thus highlighting the savagery of the Taurians.

A similar myth survives surrounding the Mares of Diomedes, one of Herakles’ twelve labors. In that story, Herakles was tasked with retrieving the mares from Diomedes, a Thracian king who fed human victims to his horses; the victims were unwitting travelers who happened upon his land. In these myths, among others, human sacrifice is closely associated with savagery and perversions of justice; and it is regularly attached to other taboos, such as cannibalism, kin killing, or violations of xenia. As we have noted throughout the Iliad, Achilles regularly violate many of these taboos that are fundamental to Greek definitions of civilization.

House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii, Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Agamemnon covers his face in mourning before the statue of Artemis. His daughter, Iphigenia is carred against her will to the altar by two soldiers. Calchas, the priest of Apollo, looks on in preparation for the sacrifice. In the sky, a nymph delivers the dear to Artemis, which the goddess will the substitute for Iphigenia.

Photo & Copyright: Carole Raddato. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

It is not surprising, then, when Achilles begins to make good his vow to commit human sacrifice and defile Hector’s corpse:

“I hail you, Patroclus, even in the House of Hades!

I am fulfilling all that I promised before,

to drag Hector here and feed him raw to the dogs,

And to cut the throats of twelve fine Trojan boys

Before your pyre, in my rage at your murder.” He spoke, and treated glorious Hector foully,

Stretching him out in the dust before the bier

Of Menoetius’ son. (22-9)

After the defilement of Hector’s corpse; slaughter of the Trojan boys; and mourning amongst Achilles, his men, and a select few of the Greek leaders; the Greeks bring Achilles before Agamemnon to recover and eat:Sample text. Click to select the text box. Click again or double click to start editing the text.

The other Greek leaders had come for Achilles

And were now escorting him to Agamemnon.

It had not been easy to convince him to come –

His heart raged for his friend. When they reached

Agamemnon’s hut, they ordered the heralds

To put a cauldron on the fire, hoping to persuade

Achilles to bathe and wash off the gore.

He refused outright and swore this oath: “By Zeus on high, there will not be

Any washing of my head until I have laid

Patroclus on the fire, and heaped his barrow,

And shorn my hair, for never will I grieve

Like this again, while I am among the living.” (40-52)

Once again, Achilles’ rage is juxtaposed with reason, “It had not been easy to convince him to come [because] his heart raged for his friend”; and he explicitly states that the defilement of Hector’s corpse and sacrifice of human victims was done “in my rage.” Once the deeds have been done, Achilles refuses to clean himself, literally and figuratively, from the savagery of battle, human sacrifice, defilement of a corpse, and his own rage. Then he makes a curious promise not to bathe until his friend is buried; yet the burial of Patroclus is continually deferred. At first, it was deferred until Achilles could slay Hector for the ceremony. Now that Hector has been slain, his corpse defiled, and the Trojan boys sacrificed, Achilles puts off the burial until the following day. Clearly, Achilles has difficulty letting go. Just as he refuses to allow Hector to pass through the gates of Hades because of his rage, he refuses to allow Patroclus to do so out of love. This is an affront to the cosmic order – the dead belong to Hades – and a threat to the civilized ethos that Apollo will address directly in the beginning of Book 24. Here, it is the spirit of Patroclus that attempts to sway Achilles’ implacable rage:

When sleep finally took him, unknotting his heart

And enveloping his shining limbs – so fatigued

From chasing Hector to windy Ilion –

Patroclus’ sad spirit came, with his same form

And with his beautiful eyes and his voice

And wearing the same clothes. He stood

Above Achilles’ head, and said to him: “You’re asleep and have forgotten me, Achilles.

You never neglected me when I was alive,

But now, when I am dead! Bury me quickly

So I may pass through Hades’ gates.

The spirits keep me at a distance, the phantoms

Of men outworn, and will not yet allow me

to join them beyond the River. I wander

Aimlessly through Hades’ wide-doored house.

And give me your hand, for never again

Will I come back from Hades, once you burn me

In my share of fire. Never more in life

Shall we sit apart from our comrades and talk.

The Fate I was born to has swallowed me….” (67-86)

Patroclus died a hero’s death, the Beautiful Death that Priam spoke of in Book 22. Yet the beauty of that death is conditional. It requires formal burial so that the psuchē (soul) of the deceased warrior may cross the river Styx and be admitted to its eternal dwelling in the House of Hades. The very term for the underworld highlights how the Greeks viewed the nature of this belonging. In English, the underworld is referred to as Hades (the same name as the god who rules the realm), but that is a slip of translation. The Greek term is the possessive form of the name (Hades’); it is shorthand for house of Hades, just as Olympus is the house of Zeus. The House of Hades is the home for the dead. Having a home, belonging, is important to humans. It underlies concepts of family, community, and civilization. This fact is poignantly made in the early 4th century by Socrates[2] wherein the old philosopher was sentenced to death. However, he had many friends at Athens and abroad who devised an escape and sanctuary for him in another polis (city-state). There, Socrates would be free to live out his days and continue to examine himself and others in his unending pursuit of knowledge. He refused his friends’ escape plans. He chose to die at Athens, as the Athenian that he was, rather than live in exile for the rest of his days. To be an exile is to be what the Greeks termed apolis, citiless.

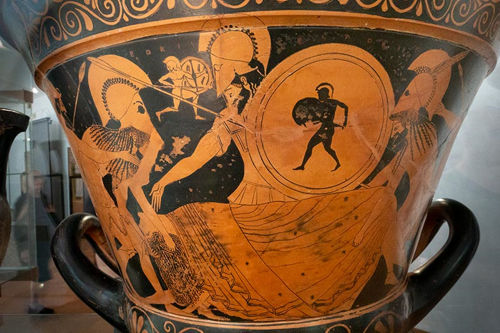

Attic red-figure kalyx krater (c. 500 BCE), by a painter of Pezzino Group.

A deceased, unnamed warrior (possibly Patroclus) carried off, the battlefield. Not the small armed figure runnig from left to right in the background. That is the psuchē of the fallen warrior looking back at his corpse as he speeds away to the House of Hades.[3]

If having a home during one’s ephemeral life is important, then it is doubly important in death, which lasts forever. Zeus made sure that Sarpedon was buried in his homeland of Lycia where he was best loved and would be most honored (Book 16); his family and friends would have access to his burial site to maintain it and give offerings to remember the deceased hero. There are differing mythological accounts regarding the fate of one’s psuchē after death, but the general idea is the same: improper treatment of the corpse results in a state of homelessness for the dead person’s psuchē. Famously, Charon, the ferryman, refuses to ferry psuchēs of the dead across the river Styx, the boundary of the House of Hades, if they have not been properly burned and buried. Whether this punishment lasts 100 years, 300, or forever, may vary. In Patroclus’ case, Charon and Styx are not even mentioned; it is the community of psuchēs themselves that make an exile of the dead hero. In every version, the psuchē of the improperly buried hero is apolis in death.

In the extreme throes of Achilles’ emotions, rage and love, he threatens to destroy the civilized order, not only of living communities (best described by Ajax’s analogy of blood money from Book 9), but also of the dead, as Patroclus’ psuchē explained above.

[1] There is evidence for it in Minoan and Carthaginian contexts.

[2] Recounted in in Plato’s Apology.

[3] Susan Woodford. The Trojan War in Ancient Art . Cornell UP (1993).