Book 19 details the delivery of Achilles’ newly forged armor by the Nereids and his formal reconciliation with Agamemnon. With these tasks complete, Achilles dawns the armor and takes to the battlefield to bring forth the death of Hector and his men along with the tears of Trojan women and children that Achilles vowed to do in Book 18. These exploits occur under the looming shadow of Achilles’ own death, prophesied by Thetis.

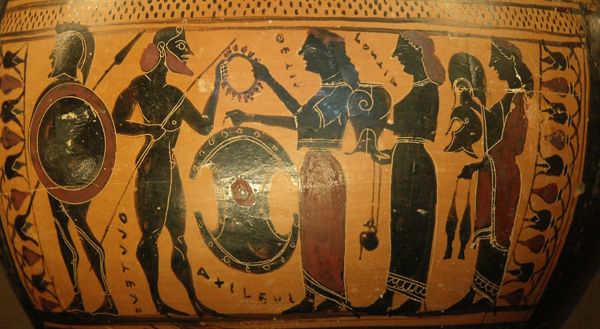

Detail of an Attic black-figure hydria (c. 550 BCE). Photo: Jastrow .

"Thetis hands her son, in “heroic nudity” and carrying a spear, a wreath of victory. With her other hand, she give him a “Boeotian” shield. Behind her a Nereid named Lomaia (“bather”? - not named by Homer) carries a breastplate and what seems a jug for oil. Behind her an unnamed Nereid carries the plumed helmet and the shin guards. To the left, an armed Odysseus keeps guard (not in Homer). The figures are labeled." (Barry B. Powell. Scenes from The Iliad in ancient art in OUPblog: 12/14/2013.)

Book 19 begins with the return of Thetis from Olympus with Achilles’ newly crafted armor:

And Thetis

Came to the ships with Hehaestus’ gifts.

She found her son lying beside

His Patroclus, wailing,

And around him his many friends,

Mourning. (4-9)

Thetis finds Achilles engaged in the same excessive mourning that characterized him in Book 18. This time, however, the corpse of Patroclus has been recovered and rests near Achilles’ ship. The excess of Achilles’ mourning that began in Book 18 becomes a running theme that ties the treatment of the dead generally in the poem to Achilles’ excesses that we discussed in Book 18. Thetis’ words confirm the excess of Achilles’ mourning:

“Achilles, you must let him rest,

No matter our grief. This man was gentled

by the gods. But you, my son, my darling,

Take this glorious armor from Hephaestus,

So very beautiful, no man has ever worn

Anything like it” (12-17)

Thetis’ message regarding the dead is twofold. First, Patroclus is mortal, and so is Achilles. As such, death is a fact of life. It is a mortal’s defining feature. We learn to live with the loss of loved ones because we must. Failure to relinquish the dead will only prevent their souls (psuchēs) from reaching their final resting place in the underworld.[1] The fate of Patroclus’ psuchē will grow more pressing and is directly related to the theme of mutilation of the corpse. Second, Patroclus’ death was brought about by a higher power; he was “gentled by the gods.” Powerful as Achilles is, he cannot rival the gods, and he is no match for those forces that are most responsible for Patroclus’ death (Apollo, Zeus, Fate).[2]

Thetis then places the armor before Achilles:

She spoke,

And when she set the armor down before Achilles,

All of the metalwork clattered and chimed.

The Myrmidons shuddered, and to a man

Could not bear to look at it. But Achilles,

when he saw it, felt his rage seep

Deeper into his bones, and his lids narrowed

And lowered over eyes that glared

Like a white-hot steel flame. (18-26)

Achilles’ rage and its fallout have loosely guided the plot of the poem for the past 18 books. The impact was largely fallout from Achilles’ refusal to fight, which caused the Greek army to fall steadily back until their most dire moments in Book 16. The character of Achilles’ rage changes with the delivery of his new armor. The rage fuses with the marrow of his bones. Achilles’ rage becomes a core part of his very being. To this point, the poem has characterized emotion as a quasi-external influence on human decisions or actions, often used as a tool by the gods to manipulate mortals. Here, however, Achilles is not simply influenced by rage: he becomes rage.

Just as it seems that Achilles is prepared to take the field, he expresses concern for the treatment of Patroclus’ corpse:

“I am afraid

For Patroclus, afraid that flies

Will infest his wounds and breed worms

In his body, now the life is gone,

And his flesh turn foul and rotten.” (35-9)

One might wonder why Achilles does not simply bury the corpse, giving his friend the funeral rites that would solidify both his legacy as a warrior and his access to the house of Hades. There are two parallel reasons that Achilles refuses to bury his deceased companion.

On the one hand, it is as simple as Achilles’ refusal to let go of his friend. In this sense, it is a denial of death. This is reminiscent of the story of Sisyphus. Sisyphus went to great lengths to avoid death. One of his attempts included convincing his wife not to bury his corpse, thus preventing the completion of his psuchē’s transition from corporeal existence to the realm of Hades. Achilles’ refusal to bury Patroclus is less a literal attempt to defeat death but, rather, a psychological refusal to let go of a loved one.

The second reason for Achilles’ refusal to bury Patroclus’ corpse is that he wishes to make good on his oath to slay Hector as a funerary offering to Patroclus. This, however, will take time, and in that time, his friend’s corpse will naturally decay to the point of an unseemly horror. It is for this reason that he expresses concern over the preservation of the corpse while Achilles goes to battle.

In both cases, Achilles acts rashly. In the first, Achilles’ desire to cling to his friend’s physical existence in the world is beyond reason for mortals. It is another example of the magnitude of Achilles’ emotions that exceed human expectations and propriety. Similarly, forestalling the burial rites for his friend so that Achilles may exact vengeance on the one who slew him as an offering at said funeral is a blatant expression of Achilles’ rage that demands unreasonable accommodations: there is no possibility of a corpse lasting long enough to accomplish such deeds without first decaying, but Achilles’ overweening rage demands the unreasonable. Achilles finds himself back in Book 9 again, wherein there is nothing Agamemnon can say or do to appease Achilles. When Ajax overtly explains that Achilles is unreasonable, Achilles agrees. Once again in Book 19, as was the case in Book 9, it is Achilles’ uncontrollable rage that governs his actions, actions that violate the norms and mores of Greek culture. Thus, Patroclus’ corpse requires divine intervention if it is to last long enough for Achilles to exact his revenge and offer-up Hector’s corpse in honor of Patroclus. Thetis promises him just that:

“Do not let that trouble you, child.

I will protect him from the swarming flies

That infest humans slain in war.

Even if he should lie out for a full year

His flesh would still be as firm, or better.

But call an assembly now. Renounce

Your rage against Agamemnon.

Arm yourself for war and put on your strength.” (41-8)

By supernaturally preserving Patroclus’ corpse, Thetis ensures honors for the deceased hero similar to those granted by Zeus for his own son, Sarpedon, in Book 16. That the deceased heroes must die is never at issue. To deny that, despite Achilles’ desires, is an impossible dream. Neither Zeus nor Thetis can keep death from the heads of mortals, but they can ensure that the fallen receive the maximum glory possible by preserving their corpses for burial. Nevertheless, the dead belong to Hades, and we have not seen the end of the conflict between Achilles’ desire to preserve Patroclus in the living world versus the cosmic imperative that mortals die and their psuchēs (souls) belong to Hades.

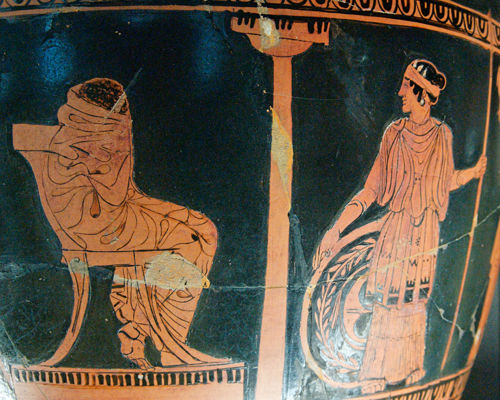

Photo: Jastrow (CC BY 3.0)

Detail of an Attic red-figure volute-krater.Louvre G 482.

Achilles depicted seated with his head and face covered in mourning. An unidentified older man leans on a staff behind him (Phoenix?). Thetis and her Nereid sisters approach him from both sides, holding pieces of gear newly forged by Hephaistos. There are no labels for any of the figures, but the basic identities are clear by context of events in Iliad Book 19. Achilles' arming scenes, both from Iliad 19 and before setting out to war in Phthia, are popular subjects in black- and red-figure.

The scene in which Achilles renounces his rage with Agamemnon is curious, both in juxtaposition to the opening scene in Book 19 (above) and its relationship to previous conversations about Achilles’ dispute with the Achaean warlord earlier in the poem – most notably Ajax’s rebuke of Achilles in Book 9. We begin with Achilles’ speech to Agamemnon:

“Well, son of Atreus, are either of us better off

For this anger that has eaten our hearts away

Like acid, this bitter quarrel over a girl?

Artemis should have shot her aboard my ship

The day I pillaged Lyrnessus and took her.

Far fewer Greeks would have gone down in the dust

Under Trojan hands, while I nursed my grudge.

Hector and the Trojans are better off. But the Greeks?

I think they will remember our quarrel forever.

But we’ll let all that be, no matter how it hurts,

And conquer our pride, because we must.

I hereby end my anger. There is no need for me

To rage relentlessly.” (68-80)

The opening line and the reference to Greek and Trojan fortunes echoes that of Nestor when he tried to intervene in the dispute between Agamemnon and Achilles in Book 1: “It’s a sad day for Greece, a sad day. Priam and Priam’s sons would be happy indeed, and the rest of the Trojans too, glad in their hearts, if they learned all this about you two fighting, our two best men in council and in battle” (1.269-73).

The cause of Achilles’ anger being over “a girl” rather than a matter of honor, self-image, or cultural memory calls to mind Ajax’s reductive simplification employed to trivialize the dispute in Book 9: “But you [Achilles], the gods have replaced your heart with flint and malice, because of one girl, one single girl while we are offering you seven of the finest women to be found and many other gifts” (emphasis added 9.657-62). In other words, Achilles and Ajax trivialize Briseis as a commodity when it suits their rhetorical needs. Recall that Achilles expressed true love for the “girl” in Book 9 when speaking to Odysseus: “Do you have to be descended from Atreus to love your mate? Every decent, sane man loves his woman and cares for her, as I did, loved her from my heart. It doesn’t matter that I won her with my spear” (348-52).

The idea that this quarrel will be remembered forever is a recurrent, self-reflective motif we first noted in Helen’s conversation with Hector in Book 6: “Zeus has placed this evil fate on us so that in time to come poets will sing of us” (6.375-6). Achilles reiterates this idea above: “I think [Greeks and Trojans] will remember our quarrel forever.”

Thus we arrive at the final lines: “But we’ll let all that be, no matter how it hurts, and conquer our pride, because we must.” These words feel somewhat disingenuous as they escape Achilles’ lips. On the one hand, he has proven himself to be the most self-aware of any mortal in the epic. On the other hand, it has been Achilles’ inability to “conquer [his] pride” that led to the death of his friend and the (near) ruin of the Greek army. This was, in fact, the very message of Phoenix in Book 9: “you have to master your proud spirit. “It’s not right for you to have a pitiless heart” (9.509-10). Nestor, too, called on Achilles to master his temper: “I appeal personally to Achilles to control his temper, since he is for all Greeks, a mighty bulwark in this evil war” (1.297-9). The truth lies somewhere in between. Achilles is the most self-aware hero in the epic. The loss of his war prize did force him to view the underlying structures of Homeric culture from an outsider’s perspective and to recognize the fundamental difference between timē and kleos, something that his contemporaries in the poem continually fail to recognize or acknowledge. He also agreed, either explicitly or implicitly, to the arguments of Nestor and Ajax. He went so far as to acknowledge that he agreed with Ajax wholeheartedly in Book 9, but he conspicuously failed to “conquer” his rage at that time: “Everything you say is after my own heart, but I swell with rage” (9.668-9). Now we must reconcile Achilles’ declaration that his anger is ended as the same one whose rage seeped deep into his bones and shone like “white-hot steel flame” in his eyes at the start of Book 19.

The answer is straightforward enough: Achilles has not conquered his pride out of necessity. His anger with Agamemnon is merely dwarfed by his desire for vengeance, the rage he feels toward Hector. Achilles’ every thought, every action, is governed by this rage. It is a constituent part of him, having seeped into his bones, as it were. This is the overweening rage that will violate the idealized Homeric notions of chivalrous combat governed and timorous action. Ajax accused Achilles of being pitiless and not acting as a civilized human being in his obstinate refusal to accept Agamemnon’s gestures of reconciliation in Book 9. Insightful as Ajax was, Achilles’ savagery was merely a figurative notion. The rage that has fused within Achilles’ bones here, in Book 19, will bring that savagery from the realm metaphor into the realm of human action.