Right: Fragmentary Bronze Ring, Engraved on Bezel (4th century BCE). J. Paul Getty Museum 85.AN.444.32.

"Hermes advancing right; his feet are winged; he wears a petasos and chalmys and holds a kerykeion (herald's staff.) The hoop of the ring is missing and the surface corroded" (Getty).

The kerykeion is Hermes' most reliable attribute. Winged sandals or helmet are less reliable but helpful. The presence of a petasos (traveller's hat) and chalmys (cloak) are also common on the god who is renowned for travelling.

This essay was written to accompany a lecture on the Long Hymn to Hermes. It follows the translation and editing of Stephen M. Trzaskoma in the Anthology of Classical Myth (Hackett). This is a very useful text for students. The translations are clean, and each hymn includes a helpful introduction and analysis. It also contains full versions of Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days.

Translations of the hymn, unless otherwise stated, are from Homeric Hymns. (trans. A. Lang, updated and modified). In Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation, 2nd ed (Kindle edition). Stephen M. Trzaskoma, R. Scott Smith, Stephen Brunet (eds.). Hackett (2016).

The best introduction for the Hymn to Hermes is included in the anthology itself:

The Hymn to Hermes is remarkable because of its amusing and lighthearted tone, which is perfectly suited to the clever, adventurous nature of the god. Immediately after being born, Hermes escapes from his crib, and the poet announces his activities on the very first day of his life.... During his first day, Hermes invents the lyre, sandals, firesticks, a form of sacrifice, and reed pipes.[1]

Hermes is the patron god of travelers, vagabonds, thieves, and liars. He is as comfortable in the wilds as within the walls of the city. This hymn narrates the playful god’s first day in existence. Like the other narrative hymns, it is chock full of aetiological elements. In addition to the invention of the lyre, sandals, firesticks, sacrificial technique, and reed pipes, the hymn explains how Hermes went from an outsider, living with his reclusive mother (the nymph Maia), to the heights of Zeus’ herald on Olympus.

Scholarly speculation places the dating of this hymn to early 5th century Olympia (in the Peloponese):

These two gods [Hermes and Apollo], both offspring of Zeus, have a special relationship in myth, particularly in Olympia, where they share an altar (see Herodorus 34). That Hermes divides the sacrifice into twelve portions also may reflect practice at Olympia. It seems probable, then, that this Hymn was recited in Olympia and, based upon linguistic peculiarities, sometime in the late 6th or early 5th century BC. [2]

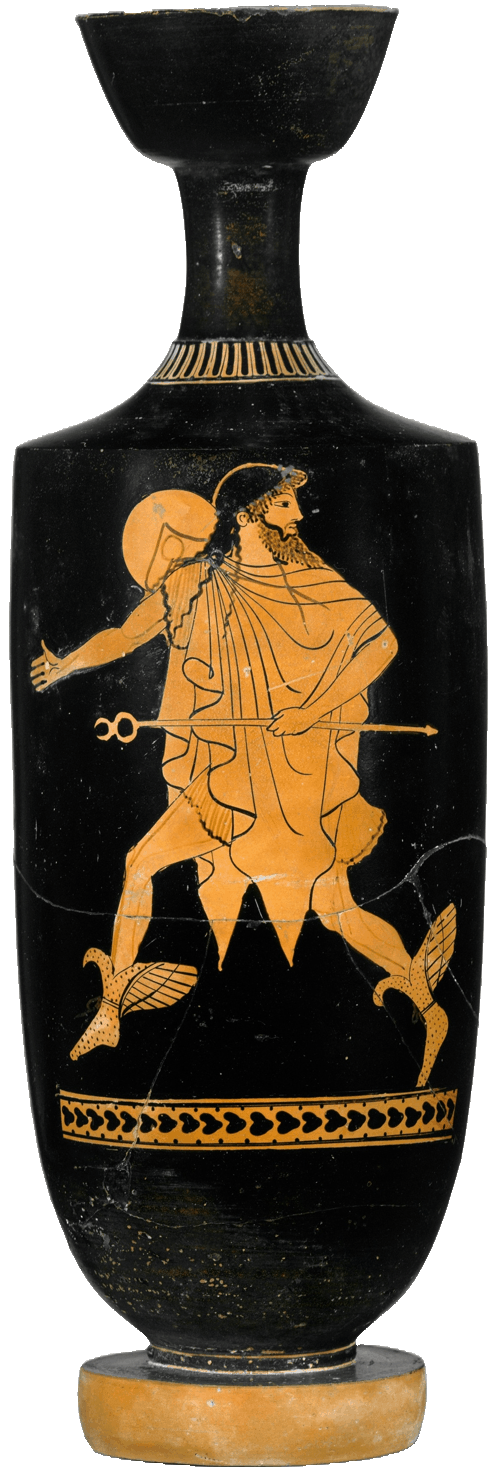

Attic red-figure lekythos attributed to Tithonos Painter (c. 480-470 BCE). MET 25.78.2

This depiction of Hermes displays his most common and recognizable attributs: "Dressed in traveling clothes with a chlamys (short cloak) and a petasos (broad-brimmed hat), he wears winged sandals and carries a herald's staff, a kerykeion, which terminates in entwined snakes. The same symbol was carried by Greek heralds as they traveled from city to city" (MET).

Hermes is regularly depicted with or without a beard, but as a second generation Olympian, his beard is always black (not white/gray).

Similarly to the Hymn to Apollo, the story of the god’s birth begins by focusing on his mother:

Sing of Hermes, Muse[...], whom Maia bore, the fair-tressed Nymph that lay in the arms of Zeus. A modest Nymph was she, shunning the assembly of the blessed gods, dwelling within a shadowy cave. There, the son of Kronos was wont to embrace the fair-tressed Nymph in the deep of night.

Maia, then, is a nymph (a minor goddess) of some beauty who willfully lives an isolated life, “shunning the assembly of the blessed gods” on Olympus. Ten months after Zeus slept with her,

[S]he bore a child of many a wile and cunning counsel, a robber, a driver of cattle, a bringer of dreams, a watcher of the night, a thief of the gates, who soon would show forth deeds renowned among the deathless gods.

Hermes’ accolades read somewhat like the rap sheet of a loveable but incorrigible rapscallion – a modern day Jack Sparrow or Shakespeare’s Puck.

The creation of the lyre is the most vivid and memorable aetiological aspect of this hymn. As Hermes exited the cavemouth of his home,

[He] found a tortoise and won endless delight, for it was Hermes who first made of the tortoise a singer.... [T]he luck-bringing son of Zeus laughed and spoke straightway, saying:

“Look, a lucky omen for me! I do not regard it lightly! Hail, companion of the feast who keeps time for the dance, you are welcome! where did you get your fine garment, a speckled shell, you, a mountain-dwelling tortoise? I am going to carry you within, and you will be a boon to me, not to be scorned by me. No, you will first serve my turn[...]. Living you will be a spell against ill witchery, and dead a very sweet music maker.”

The young god then emptied the shell of its inhabitant, boring holes into it, setting stalks of reeds and ox hide within. He positioned the ox’s horns on either side of the shell and used sheep-gut for string. Voila! The first lyre was created by Hermes on his first day of existence.

Then he took his treasure when he had fashioned it and touched the strings in turn with the plectrum,[3] and wondrously it sounded under his hand, and the god sang sweetly to the notes.

The larger narrative of the hymn centers around the theft of Apollo’s cattle by the mischievous – and hungry! – young Hermes. The last lines of the section alludes to this activity:

He took the hollow lyre and laid it in the sacred cradle; then, in longing for flesh of cows he sped from the fragrant hall to a place of outlook with such a design in his heart as robbing men pursue in the dark of night.

This inclination to thievery “as robbing men pursue in the dark of night” associates Hermes with thieves, highwaymen, and general mischievousness.

Lucanian Red-Figure Volute Krater (detail). Attributed to the Palermo Painter (c. 415-400 BCE). J. Paul Getty Museum 85.AE.101.

"Hermes leans on a pillar inscribed with his name" (Getty). The kerykeion (herald's staff) is the only attribute present. This tends to be the case for Hermes: the winged sandals or helmet, petasos, and chalmys come and go, but the god is rarely depicted without the kerykeion present. Note also that Hermes is beardless in this painting. Although black-figure depictions lean toward beards on the younger Olympians (with the conspicuous exception of Apollo), Hermes, Dionysos, and Hephaistos are as likely as not to be depicted without beards in Classical and Hellenistic art. This is in stark contrast to Zeus and Poseidon, who are consistently portrayed with beards throughout the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods, befitting their status as Patriarchs.

Over the course of driving the stolen cattle, Hermes demonstrates his crafty nature in the creation of sandals and devising a means by which to disguise the direction that he drove them:

From their number did the keen-sighted Slayer of Argos, the son of Maia, cut off fifty loud-lowing cows and drive them here and there over the sandy land, reversing their tacks, and mindful of his cunning, confused the hoof-marks, the front behind, the hind in front, and himself went backward.

In other words, Hermes walked, and had the cattle walk, backwards to disguise the direction of their trek. Then he creates sandals:

Straightway he wove sandals on the sea-sans (things undreamed he wrought, works wonderful, unspeakable), mingling myrtle twigs and tamarisk; then binding together a bundle of the fresh young wood, he shrewdly fastened it for light sandals beneath his feet,[...] inventing as he hastened on a long journey.

“To create a confusing sight for the cows’ movement, Hermes simply turns them around and makes them walk backwards (76-8); but to conceal his own footprints, he devises a novel form of footwear, made from interwoven switches of tamarisk and myrtle, which, when worn, leave very large and confusing marks on the ground (79-86).”[4]

Note that his creation is described as both “undreamed” and “wonderful”; they are an original invention, a technē (origin of the term technology) that benefits mankind: “Hermes’ sandals were inventions of the moment, meant to serve the needs of a particular situation: they could be (and were) readily discarded when that need had been met.”[5] Thus, Hermes’ creative endeavors are a boon to human civilization in much the same way Apollo’s action in slaying Pytho is in the Hymn to Apollo. But Hermes is an actual monster slayer too. The hymn refers to him as “Slayer of Argos” (rather anachronistically). Argos was a hundred-eyed giant assigned to shepherd Hera’s flocks and stand as prison guard over the mortal Io. Hermes famously slew the monstrous giant, earning for himself the title, “Slayer of Argos” in the same way that Apollo earned the title “Pythian Apollo.”

Little of significance occurs in the remaining lines of the section except that we learn, for the first time, to whom the stolen cows belong: “Phoibos Apollo.” Beforethis point, the hymn only noted that Hermes has stolen cows from “where the deathless cows of the blessed gods ever had their haunt.”

This section narrates Hermes’ invention of “firesticks” and the ritual for preparing and performing a sacrificial victim. This is one of two popular myths surrounding the origin of sacrifice. The other is in Hesiod’s Theogony and stems from a dispute between Zeus and Prometheus.

The “firesticks” that Hermes devises “would be a tool of repeated value to humankind, for it gave mortals the ability to re-kindle a fire without having to fetch a living flame from one already burning to ignite another. Hermes’ fire-sticks (108-11) were an improvement on Prometheus’ earlier theft of a living flame from Hephaistos’ hearth.”[6] Thus, the theme of Olympians “civilizing” the world in the reign of Zeus continues from Hesiod to the Homeric hymns.

The hymn reinforces some of the important aspects of sacrifice in the Greek world: The process of butchering the victim is detailed, including the slitting of the throat, spitting of fat & flesh, collection of blood, stretching of hide, and then setting out the portions. Finally, and perhaps the most telling bit of information for our purposes, the hymn explicitly states the relationship between sacrifice and god:

Then a longing for the rite of the sacrifice of flesh came on renowned Hermes, for the sweet savor inflamed him, immortal as he was, but not even so did his stout heart allow the flesh o slip down his sacred throat, but rather he placed both fat and flesh in the high-roofed stall and swiftly raised it aloft, a trophy of his robbing. Then, gathering dry firewood, he burned heads and feet entire within the vapor of flame.

Thus, the material prize that the gods receive in the

sacrificial ritual is rationalized as the sweet savor that wafts up to the sky.

The gods do not eat the flesh of the victims. Greeks ate, in fact originated,

the “Mediterranean diet”: greens, cheeses, olives, and figs. Fish supplemented

their meals when available. However, despite widespread practice of animal

husbandry, the slaughter and consumption of red meat (beef, lamb/sheep, etc.)

was reserved for special occasions. The animals were too rare and valuable for

daily or weekly consumption. During festivals, however, when animal sacrifices

were made, the edible parts of the animal, the fat and flesh, were reserved

while the inedible parts were burned to the gods. The edible portions would be

cooked and distributed amongst the worshippers who would enjoy the relatively

rare delicacy of red meat.

The section concludes with an interesting

conversation between Maia and her erstwhile child. She chides Hermes for his

mischievousness and warns him of dire consequences for it. In his reply to her,

he reinforces his role as patron god to thieves and liars, among other things:

Mother mine, why would you scare me so, as though I were a silly child with little craft in his heart, a trembling babe who dreads his mother’s chidings? No, but I will try the wiliest craft to feed you and me forever. We two are not to suffer remaining here, to be alone of all the deathless gods to be unapproached with sacrifice and prayer, as you command. It is better to spend time with immortals day in and day out, richly, nobly, well fed, than to be homekeepers in a dismal cave. And for honor, I too will have my dues of sacrifice, just like Apollo. Even if my father does not give it to me, I will endeavor – for I am capable – to be a captain of robbers. and if the son of renowned Leto tracks me down, i think some worse thing will befall him. For to Pytho I will go to break into his great house, from where I will steal fine tripods and cauldrons enough and gold and gleaming iron and much clothing. If you care to, you yourself will see it.

Hermes’ “craft” is his mind, particularly the guile that he uses to trick others. Such deceits were a positive character trait in archaic literature. Odysseus enjoyed great fame as the featured hero of Homer’s Odyssey and a favorite of Athena (Olympian goddess of wisdom and helper of heroes). Although a “wily” mind was the subject of great ambivalence in the Classical period when it was associated with sophists and the Intellectual Revolution. Such ambivalence is on full display in a pair of surviving plays by Sophocles: the Ajax and the Philoctetes. In the former, Odysseus uses his skill with words to facilitate the burial of his “frenemy,” Ajax, in which his virtue of cleverness is juxtaposed to Ajax’s physical attributes. In the latter, Odysseus is the epitome of 5th century Athenians’ darkest fears about the new generation of aristocrats, trained by sophists, who were (in)famous for their manipulation of language arguing subjectivity of truth and relativism in general (part of the curriculum in the art of oratory or rhetoric).

Apollo is on the case to track down his cattle. He seeks help from the old man who had seen a young child driving cattle backward the prior day, and then Apollo read a bird sign (augury) informing him that the thief was none other than Hermes, the son of Zeus. Apollo is impressed by Hermes’ keen tricks with his newly constructed footwear that were designed to disguise his tracks and appear like no known creature. At last, Apollo finds his way to Maia’s cave to confront his half-brother over the theft of his cattle.

Hermes’ reputation as a trickster, liar, thief, and rogue is reinforced during his interaction with Apollo:

“Child, you who are lying in the cradle, tell me straightway of my cows, or speedily between us two there will be unseemly strife [...].” Then Hermes answered with words of craft: “Apollo, what ungentle word have you spoken? [....] I did not see them or ask of them or give ear to any word of them. Of them I can tell no tidings nor win reward for telling. [....] I have nothing to do with this. But other cares have I: sleep and mother’s milk and about my shoulders swaddling bands and warmed baths. [....] And a truly great marvel among the immortals it would be that a newborn child should cross the threshold after cows of the homestead; a silly story of yours. Yesterday I was born, my feet are tender, and rough is the earth below. But if you want, I will swear the great oath by my father’s head that neither I myself am to blame, nor have I seen any other thief of your cows – whatever these cows are, for this is the first I’ve heard of them.”

Hermes clearly clings to his bluff about the cattle, shielding himself behind the guise of a newborn child. After a short struggle and possibly the world’s first fart joke, Apollo begins to carry Hermes away, and the latter invokes Zeus to judge the dispute, which will be the subject of the next section.

The hymn succinctly lays out the positions of Apollo and Hermes as they bring their dispute before Zeus:

Now lone Hermes and the splendid son of Leto were point by point disputing their case. Apollo with sure knowledge was righteously seeking to convict renowned Hermes for the sake of his cattle, but the Cyllenian [Hermes] sought to beguile with craft and cunning words the god of the silver bow. But when the wily one found one as wily, then speedily he strode forward through the sand in front, while behind came the son of Zeus and Leto. Swiftly they came to the crests of fragrant Olympos, to father Cronion they came, these fine sons of Zeus, for the balances of doom were set for them there.

Apollo is secure in his knowledge. This befits his character. He is, after all, a sun god and an oracular deity. Hermes, on the other hand, is characterized by guile, the cunning manipulation of words. In Apollo, however, Hermes seems to have met an opponent who can match his maneuvering.

Finally, note that they take their dispute to Olympus, the house of Zeus, who is not only the patriarch of the family, but also the seat of justice and dispenser of fate: “the balances of doom were set for them there.” Zeus communes with the fates regularly, and then he enforces their collective will. This, in Theogony and elsewhere, is what is referred to as the justice of Zeus, the just order that Zeus brought to the cosmos when he defeated Kronos and the Titans. Earlier, we observed that Hermes was called the “Slayer of Argus,” Apollo “the Pythian,” and that the many tales of heroes slaying monsters represented the conquest of civilization over savagery, civilizing activities, or simply reason over irrationality. Each of these victories, be them by Apollo, Hermes, Perseus, or Herakles, are extensions of the justice of Zeus, the taming, ordering, or civilizing of the cosmos.

Caeretan hydria (c. 530 BCE). Louvre E 702.

There is some dispute as to the subject of this scene, but it remains the best surviving visual narrative of the myth told in the Long Hymn to Hermes.

Zeus (bearded figure at right) judges dispute over cattle (far left) between Hermes (center, in crib) and Apollo (beardless, possibly left or right of crib), while Maia looks on (one of the beardless figures surrounding the crib).

Note the line that appears to shoot out behind Maia’s head. That represents the cave mouth. In this version of the myth, the judgement takes place in Maia’s cave rather than Zeus’ home on Olympus. The cattle can be seen at the other end of the cave (a rabbit runs up the hill outside the cave).

The two gods pleaded their cases to Zeus, Hermes lying as he did before, but Zeus knew clearly that he was untruthful and took great joy in his bold son. Nonetheless, Zeus commanded Hermes to return the cattle:

But Zeus laughed aloud at the sight of his evil-witted child, so well and wittily he pled denial about the cows. Then he bade them both be of one mind and so seek the cattle, with Hermes as guide to lead the way and show without guile where he had hidden the sturdy cows. The son of Cronos nodded, and glorious Hermes obeyed, for the counsel of Zeus of the aegis persuades easily.

First, Zeus cannot be fooled. He is, after all, the ruler of

the pantheon, responsible for dispensing justice and the dictates of fate. That

Hermes quickly obeys his father is telling for two reasons: 1) Zeus is his

father. He is the head of the household. It would be unseemly to defy a father’s

commands. 2) Zeus is named “of the aegis.” The aegis of Zeus is a magically

imbued goatskin cloak. It is almost exclusively depicted on Athena (another

offspring who functions as an extension of Zeus’ will), but it belongs to Zeus,

and serves as something of a mythical plate of armor for the god. The reference to the aegis is a reference to Zeus’ power and the threat of

violence if he his crossed. That Hermes complies with Zeus’ command shows him

to be a dutiful son and a wise thinker; he acknowledges the implicit threat of

challenging Zeus’ power and the wisdom of Zeus’ counsel.

Lastly, Hermes is

described “as a guide to lead the way.” This is a

major function of Hermes in his role as herald of Zeus. He is a guide. Indeed,

he is the guide; he even guides the souls of the dead to the river Styx

where they book passage to Hades with the ferryman, Charon. See inset below.

One of Hermes' major functions in Greek religion was that of psychopompos, "guide of souls." It was Hermes' responsibility to guide the souls of the dead to the underworld, or at least the outskirts of the underworld, where they would meet Charon, the ferryman, who would ferry the souls of those who had been properly buried across the rivers Acheron or Styx. Incidentally, Charon also fullfills the role of psychopompos in this relationship. In this Gallery, we see Hermes acting as psychopompos, delivering or guiding souls of the dead toward their final resting place.

The exchange of gifts between Hermes and Apollo marks the end of any enmity between the half-brothers, and it supplies an aetiological explanation for Apollo’s most popular attribute, the lyre. Hermes, his nature clearly established as crafty and cunning, does not simply offer up the instrument to Apollo. He baits the hook, as it were, first casually removing the lyre and plucking a few strings, then launching into a melodious song. Apollo is enchanted and delighted by the verse. Only then does Hermes offer the instrument over to Apollo, so enamored with his gift that he all but forgets about the cattle. The two make a formal pact of friendship and Apollo bestows upon Hermes an equally important attribute, the caduceus or kerykeion; it is the messenger’s or herald’s staff, and the one constant attribute in visual depictions of Hermes.

This essay closses with a discussion about the content of the song Hermes performed that won Apollo's heart. We have made many references to Hesiod’s Theogony over the course of these essays on the Homeric hymns. Many of the hymns were created in the latter half of the Archaic period, the same period as Hesiod and Homer, and all of the hymns share the same characteristic of venerating archaic epic, hence naming the collection Homeric hymns: they maintain the same Archaic meter of Homeric epic. It should come as no surprise, then, that these hymns generally agree with and perpetuate themes found in the Homeric and Hesiodic epics, even if they do not conform closely in plot action – i.e., they do not simply copy and repeat the stories from Hesiod and Homer, but the themes are largely similar. This shines through particularly in Hermes' musical performance at the end of the hymn. His song follows below:

Taking his lyre in his left hand he tuned it with the plectrum, and wondrously it rang beneath his hand. At that Phoibos Apollo laughed and was glad, and the pleasant note passed through to his very soul as he heard. Then Maia’s son took courage, and sweetly harping with his harp he stood at Apollo’s left side, playing his prelude, and his delightful voice followed upon it. He sang the renown of the deathless gods and dark Gaia, how all things were in the beginning and how each god got his portion. To Mnemosyne, first of gods, he gave the reward of his song, the mother of the Muses, for the Muse came upon the son of Maia. Then the splendid son of Zeus honored all the rest of the immortals, in order of rank and birth, telling duly the entire tale as he struck the lyre on his arm.

Compare that description to Hesiod’s description of the Muses in the opening to Theogony:

Let us begin singing of the Heliconian Muses,

Who inhabit the high, holy mountain of Helicon.

They dance on gentle feet near a violet spring

Around the altar of the mighty son of Kronos.

[....]

They make beautiful and charming choruses atop

Mt. Helicon. Their steps thus strengthened, they

Rise and go forth veiled in a broad mist.

Nighttime dancers spreading their sweet voices,

They sing of aegis-bearing Zeus and reverend Hera,

The Lady of Argos who walks with golden sandals;

And the bright-eyed daughter of aegis-bearing Zeus, Athena;

Both Phoibos Apollo and arrow shooting Artemis;

And also Poseidon the earth-shaker, who holds up Gaia;

And august Themis; and Aphrodite with flickering lashes;

Gold-crowned Hebe; and beautiful Dionē;

Leto; Iapetus; and crooked-counseling Kronos;

Aurora; and Helios; and splendidly radiant Selēnē;

Gaia; mighty Okeanos; and dark Nyx;

And other deathless ones, the divine race enduring forever.

[....

The Muses] breathed into me divine speech,

That I might celebrate the things that will be and those that have been.

They commanded me to sing of the blessed race that endures forever,

And always to sing of them first and last. [7]

In both compositions, the entertainment value of music is important (the lyrics and plucking of the lyre). The songs delight the listener or audience member. Also in both, the content of the performances honor the gods, listing them in order by which they are honored, and pride of place is given to the Muses or their mother, Mnēmosunē (Memory). Lyrics (words sung to the accompaniment of a lyre) and music (the art of the Muses) both entertain and facilitate memory. The Homeric hymns, like the Theogony, Iliad, Odyssey, etc. participate in this musical/poetic tradition that is creative (poeisis), commemorative (gives kleos, “fame” to its subjects), and entertaining. See my analysis of the Invocation to the Muses for further discussion of this topic.

Euboean Black-Figure Neck Amphora (c. 570–560 BCE). J. Paul Getty Museum 86.AE.52.

"On this vase, the three goddesses trail along behind Hermes, who is identified by his kerykeion. Paris steps forward and shakes hands with Hermes, accepting his fate. The other side of the vase depicts a scene of two men between sphinxes" (Getty).

Hermes is shown here in his capacity as herald of Zeus and guide of travelers, leading the goddesses to Paris, whom Zeus appointed to judge a dispute over a golden apple. This is one of many surviving black-figure depictions of Hermes leading the goddesses toward Paris in which the identity of the goddesses is not possible to discern because they lack attributes. In the myth of the Judgement of Paris, Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite compete over who should receive the appl and thus be judged most beautiful.

[1] Palaima, Thomas G.. Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation (p. 187). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

[2] ibid.

[3] Plectrum. A thin flat piece of plastic, tortoiseshell, or other slightly flexible material held by or worn on the fingers and used to pluck the strings of a musical instrument such as a guitar (Lexico.com).

[4] Arlene Allan. Hermes. Routledge (2018).

[5] ibid.

[6] ibid.

[7] Hesiod. Theogony. Lines 1-34. Trans. Daniel Gremmler.