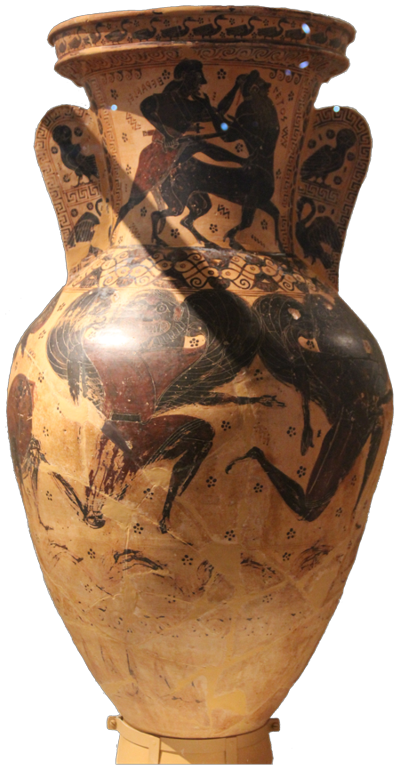

Right: Corinthian black-figure column-krater (c. 550 BCE). Boston 63.420.

Herakles and Hesione do battle with a ketos (sea monster).

Photo: Dan Diffendale. Copyright: (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), background removed.

Herakles accomplished a number of other famous exploits in and around the 12 labors. One of the more prolific events included rescuing the princess of Troy (Hesione) from a ketos (sea monster) in a virtual carbon copy of the exploit Perseus accomplished in another part of the Mediterranean. Herakles went to war with and, in fact, conquered Troy a generation before the famous Trojan War of the Iliad. He fought numerous battles throughout the Greek world and won numerous prizes (and brides!). We will cover some, but by no means all, of those exploits below. It is likely that many of these exploits were the accomplishments of local heroes whose identities were amalgamated into the Herakles myths and/or attempts of various city-states to claim a portion of "ownership" of the Herakles inheritance. As I've stated in a few places, Herakles was the most Panhellenic of Greek heroes, and virtually every major polis claimed some sort of connection to him, often through the bloodlines of his many encounters with women and the proliferaiton of his children throughout the Greek world in the succeeding generation (the Herakledai - children of Herakles).

Although it's more common to rely on Apollodorus for our introductory surveys, I'm going to begin with Hyginus because he organizes Herakles exploits in the same way that modern scholars tend to, by separating the 12 labors from the "side labors." However, his list isn't very extensive, so it is only a starting point. Also, Hyginus offers only brief description of each exploit, so we will return to Apollodorus for more detailed analysis as needed. Many of these myths survive in the visual record as well. Indeed, many of them are as popular or moreso than many of the 12 labors when taken individually. Here, then, is Hyginus:

Hyginus 31 Hercules’ Side-Labors

[1] In Libya he killed Antaeus son of Earth, who compelled all visitors to wrestle with him, wore them down, and killed them. Hercules wrestled him and killed him.

[2] In Egypt he killed Busiris, who regularly sacrificed foreigners. When Hercules heard Busiris’ decree, he allowed himself to be led to the altar dressed in the sacrificial headdress. But when Busiris was about to invoke the gods, Hercules killed both him and his sacrificial attendants with his club.

[3] He overcame Mars’ son Cygnus in battle and killed him. When Mars arrived and tried to engage him in a battle over his son, Jupiter sent a thunderbolt between the two and so separated them.

[4] At Troy he killed the sea monster that was about to devour Hesione. He shot dead Hesione’s father, Laomedon, with arrows because he refused to hand her over as agreed.

[5] He also shot dead the insatiable eagle that devoured Prometheus’ heart.

[6] He killed Lycus son of Neptune because he tried to kill Hercules’ wife, Megara daughter of Creon, and his sons, Therimachus and Ophites.

[7] The river Achelous could change himself into any form he wanted, and when he and Hercules were fighting over the right to marry Deianira, he turned himself into a bull. Hercules broke off one of his horns and gave it to the Hesperides (or Nymphs); these goddesses filled the horn with fruit and called it the Cornucopia {“Horn of Plenty”}.

[8] He killed Neleus son of Hippocoon and ten of his children because he was not willing to cleanse or purify him after he killed his wife, Megara daughter of Creon, and his sons, Therimachus and Ophites.

[9] He killed Eurytus because he wanted to marry his daughter Iole and was rejected by him.

[10] He killed the Centaur Nessus because he tried to rape Deianira.

[11] He killed the Centaur Eurytion because he wanted to marry Deianira, Dexamenus’ daughter, who was his fiancée. [1]

Herakles' encounters with Antaios and Bousiris took place during the 11th labor, the apples of the Hesperides. Herakles journeyed across northern Africa (everything west of Egypt was liberally labeld "Libya") to find Nereus, the sea god who would tell him where the grove of the Hesperides was located. On his way to and fro, Herakles encountered the giant Antaios and the Egyptian king Bousiris. Both of these exploits are very similar in theme, and share that similarity with the early labors of Theseus: the violation of xenia and punishing wrong-doers.

Antaios was a giant, literally meaning "born from Gaia." Giants (including cyclopes who were basically one-eyed giants but not born of Gaia) were alike to centaurs, satyrs, and Amazons in Greek myths insofar as they were used to represent the savage or barbarian "other." While satyrs were portrayed as comical or ridiculous and affable if foolish creatures, giants, centaurs, and often Amazons were treated with a sharper edge. They were in their turns, ornery, warlike, quick to anger, disrespectful toward the gods, and unlawful. As Hyginus wrote, Antaios would force travelers who entered his territory to wrestle him, and when he won, he killed them. According to Apollodorus, Antaios was invincible so long as his feet remained touching the earth, because he drew power from Gaia, his mother. So Herakles defeated him by lifting him off the ground, thus severing his connection to Gaia, and broke the giant's back. This same basic myth is mimicked in Theseus' encounter along the isthmus of Corinth when Kerkyon, who, "used to force passing travelers to wrestle and would kill them when they did," challenged Theseus, who "lifted him up high and then slammed him to the ground," killing him.[2]

Bousiris was king of Egypt and a son of Poseidon who would violate the laws of xenia (hospitality, guest-friendship) by sacrificing strangers in his land in order to maintain the fertility of the soil. This savage sort of sacrifice ascribed to barbarians is also applied to the Taurians in Euripides' tragedy,Iphigenia among the Taurians, in which the Taurians would sacrifice foreigners, who had the misfortune of landing on their shores, to Artemis for the goddess' benevolence. Diomedes, the king of Thrace who fed strangers to his mares is another popular example of this mythic template. In any case, Bousiris tried to sacrifice Herakles as he made his way back east across northern Africa, and it did not go well for the Egyptian king. As was the case with Antaios, barbarian or savage figures who violated or perverted the laws of xenia were dispatched by the hero, and the justice of Zeus was asserted in the land.

Attic red-figure kylix (c. 500 BCE). Athens 1666.

Herakles wrestles with the giant Antaios in Libya. Both figures are named on the vase.

Photo: Jerónimo Roure Pérez

Copyright: (CC BY-SA 4.0), background removed.

Attic red-figure pelike from Boeotia (c. 500-450 BCE).

Athens 9683.

Herakles near the altar, killing Bousiris and his priests.

Photo: Marsyas / Wikimedia

Copyright: (CC BY-SA 2.5), background removed.

Herakles' interaction with Laomedon and Hesione at Troy might be his most prolific "side quest," and it largely falls under the radar. He defeated a ketos (sea monster) and put together an expedition that successfully conquered Troy - the impenetrable, god-built walls of Troy...that a generation later, an army of united Greek forces from all over the Aegean could not breach in 10 years of trying. Apollodorus notes that Herakles' return journey from the Asiatic home of the Amazons with the Belt of Hippolyte took him past the city of Troy, ruled by Laomedon:

It happened at that time that the city was in difficulties because of the wrath of Apollo and Poseidon. For Apollo and Poseidon, desiring to test the insolence of Laomedon, made themselves look like mortals and promised to build walls around Pergamon for a fee. But after they built the walls, Laomedon would not pay them. For this reason Apollo sent a plague, and Poseidon sent a sea monster that was carried up on shore by a tidal wave and made off with the people in the plain. The oracles said that there would be an end to the misfortunes if Laomedon set out his daughter Hesione as food for the sea monster, so he set her out and fastened her to the cliffs near the sea. [3]

This episode is so remarkably similar to the story of Perseus and Andromeda on the other side of the Greek world that one might wonder whether the Windows shortcuts for copy and paste aren't the oldest editorial tools in publishing history.[4] In any case, Herakles noticed Hesione chained, he made a deal with Laomedon to save her and slay the ketos (sea monster). However, Hesione was one of only a few princesses Herakles did not show interest in sexual relations with, or he simply valued the prized mares in Laomedon's stables more. Herakles agreed to rescue Hesione in exchange for the mares. The horses were, to be fair, very special. They were from Zeus' stables given to Laomedon's grandfather, Tros, as compensation for the rape of his son and heir, Ganymede.[5] Laomedon reneged on his deal once Herakles rescued Hesione, and Herakles swore revenge, but he hadn't the time at the moment as he was still obligated to serve Eurystheus.

Herakles made good on his threat to kill Laomedon for his treachery after his twelve labors were completed, and he amassed an army of Greeks to sack Troy and punish its unjust ruler. He slew Laomedon, gave Hesione over to his companion, Telemon (father of Ajax in the Iliad), and left Priam, Laomedon's young son, to rule the city.

So much for the impentrable walls of Troy built by Poseidon and Apollo. They were breached a generation before the Trojan War and with a far smaller army. That said, as I've discussed elsewhere, the idea of a cohesive narrative structure to all of Herakles' exploits or between the corpus of Herakles' myths with those of others in the klea andrōn is a "myth" in itself. These stories (muthoi) were composed in numerous places by varied people separated by as much as a millenia. Many of Herakles' exploits are surely composites from other local heroes and/or inherited and altered from Near Eastern myths. The idea that there is one chronologically coherent narrative that fits seamlessly within all the other heroic narratives or that there is a definitive version of Greek myth is something new students need to divest themselves of quickly. Herakles sacked Troy with eighteen ships half a century before the Trojan War that was depicted in the Iliad. The walls of Troy were impenetrable, and a thousand ships worth of Greeks could not knock them down. the two stories are contradictory and true in their own turn. There is a significant degree of fluidity one must accept as we study these stories.

Roman terrocotta relief (late 1st-early 2nd century CE) from necropolis of Lugone in Salo. Museo Civico Archeologico della Valle Sabbia in Gavardo.

Herakles about to kill Laomedon with arrow as the king falls back and reaches out pleadingly. Hesione stands behind Herakles with head down and body turned away.

Photo: Jastrow.

Auge is one of the more famous (or infamous) sexual encounters in Herakles' myths. She was the princess of Tegea (a polis in the central Peloponnese - Arcadia). Herakles outright raped her; In Trzaskoma's translation of Apollodorus, "Herakles forced himself on her without realizing she was Aleos' daughter"[6] (Aleos was the king of Arcadia). Continuing to follow Apollodorus' version...

She gave birth to the baby in secret and set him down in the sanctuary of Athena. But Aleos entered the sancuary because the land was being devastated by a plague and discovered after a search that his daughter had had a child. So he exposed the baby on Mount Parthenios, but by the gods' providence it was saved. For a deer that had just given birth offered her teat to the baby, and some shepherds took him up and named him Telephos. Aleos gave Auge to Nauplios son of Poseidon to sell into slavery in a foreign land. Nauplios gaver her to Teuthras, the ruler of Teuthrania, and he made her his wife.

Apollodorus doesn't specify why Aleos exposed the child. It may simply have been outrage over the embarrassment of a daughter giving birth out of wedlock. However, the fact that he found her out while visiting the sanctuary of Athena on account of a plague may suggest that purging his land of the their taint was a prerequisite to placating the gods and bringing an end to the plague. Similar circumstances surround, for example, Thebes in Sophocles' Oidipous Tyrannos wherein the polis suffers a heaven-sent plague that will persist as long as the murderer of the polis' former king continues to live unpunished in the polis. It is difficult to view Auge, who was raped, as anything but a victim, but then again, much of what makes for the haunting beauty of Sophocles' tragedy is the good intentions of Oidipous juxtaposed with the inadvertent nature of his heinous crimes. Both Sophocles and Euripides composed tragedies surrounding the rape of Auge and its consequences. Emma Stafford summarizes what is known from the lost tragedy, Auge, by Eurpides:

Euripides' version focused closely on Auge's plight and Herakles was certainly amongst the dramatis personae. The play would have begun with a prologue outlining preceding events, which do not seem to have included any oracle: Auge had been performing a night-time ritual forAthena at a spring near the temple when Herakles raped her while drunk, leaving behind a ring: the birth of the resulting baby has now brought pollution to the temple, where the child is concealed. The action then would have centered on Aleos' search for the cause of the pollution, discovery and exposure of the baby and Auge's condemnation to death. Herakles happens to return to the area, finds the child being suckled by a deer and, recognizing the ring which Auge has left with him, realizes what must have happened. Herakles is repentant and persuades Aleos to relent, and the play may well have ended with a god instructing Auge to take the child to Mysia where they will both find sanctuary with Teuthras.

[....]

More striking still is the fact that Herakles explicitly refers to the rape as wrongdoing, even if he does resort to the perennial excuse of drunkenness: The wine drove me out of my senses; I admit that I did you an injustice, but the injustice was not intended." [7]

As we would expect in 5th century tragedies, the morality of rape, infanticide, exposure, and other taboos in myth are presented with a critical eye. There are, however, certain consistencies in the myth: 1) Herakles raped Auge; 2) The offspring of that rape was Telephos; 3) Aleos attempted to rid his land of both Auge and Telephos; 4) Auge and Telephos found themselves living on the other side of the Aegean in Mysia (west coast of Anatolia/Turkey) in the home of the king of Mysia. Eventually, Telephos would rule in Mysia, a fact important to stories surrounding the Trojan War. As regards Herakles, this tale casts the net of our heroes' progeny across the Aegean into Asia Minor and is a prime example of the ways in which various poleis are connected to the panhellenic hero Herakles.

Bronze mirror case from Elis (c. 325 BCE).

This is the outter clamshell of a mirror. Auge is pulled to bed by a drunken Herakles. Note that she is depicted resisting his pull with her feet and legs braced, back hunched, and arms bent as if pulling back or trying to disengage from Herakles' grasp.

Photo: Giovanni DallOrto

Marble relief (2nd century BCE), Pergamon.

Carpenters building a boat in which to send Auge into the sea.

Photo: Marcus Cyron

Copyright: (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Deianeira was the Daughter of Oineus, king of Kalydon in Aetolia (northern coast of the Gulf of Corinth). She was variously courted or kidnapped by the river god Acheloos (Acheloos was the river separating Aetolia from Acarnania). Herakles struck a deal with Oineus that if he were to rescue the princess, he could have her hand in marriage. Herakles confronted and defeated the god, who did battle in the form of a bull, which the hero subdued. The more popular part of the myth is what happened as Herakles brought Deianeira, his new prize, back home:

Taking Deianeira, he came to the Euenos River, where Nessos the Centaur stationed himself and ferried passersby across for a fee, saying that he had been set up as ferryman by the gods because of his righteousness. Now, Heracles crossed the river by himself, but he was asked for the fee and entrusted Deianeira to Nessos to carry across. But while Nessos was ferrying her across, he tried to rape her. When Heracles heard her crying out, he shot Nessos through the heart as he was coming out of the river. Just before he died, Nessos called Deianeira over and told her to mix the seed that he had discharged onto the ground with the blood that was flowing from the arrow wound in case she ever wanted a love potion to use on Heracles. She did this and always kept it nearby. [8]

The end of Apollodorus' description foreshadows the death of Herakles, a popular topic in 5th century tragedy and later epochs. However, Herakles' confrontation with the centaur Nessos was well known in the Archaic period. Note that he does not necessarily slay the centaur with the poison-tipped arrows coated with the blood of the Lernean hydra. That aspect of the myth is only relevant to the later stories surrounding the death of Herakles. It seems the hero's conflict with Nessos may predate stories surrounding Deianeira and the poison-coated cloak that would lead to Herakles' eventual death. Even late Classical work, such as Louvre K 537 (below), often represent the confrontation without the arrows. This could be due to narrative convention (limited canvas on a vase does make the depiction of bow use less realistic because it forces a compression of space); the close quarters weapon of sword or club is simply more visceral, or the paintings may simply represent different iterations of the same myth. It the case of Athens 1002 from the late 7th century (below), the latter seems likely. However, Louvre K 537 is a Lucanian vase from southern Italy, and many scenes from that area in the Greek world are known to take 5th century Athenian tragedy as their inspiration, and existing tragedies from Aeshylus, Sophocles, and Euripides have proven to vary significantly from Archaic iterations of the same myths.

Photo: Gary Todd

Attic black-figure neck-amphora attributed to the Nessos Painter (c. 620-610 BCE). Athens 1002.

Herakles grasps the Nessos by the head while bracing him in place with his foot on the centaur's back as he thrusts a sword into the creature's back.

Photo: Μαρσύας. Copyright: (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Lucanian red-figure nestoris (c. 360-350 BCE). Louvre K 537.

Herakles and the centaur Nessos. Herakles wears his signature lion skin cloak and brandishes his similarly iconic club.

Photo: Jastrow.

The Giantomachy is probably the most popular event in which Herakles takes part, outside of the 12 Labors, and it is represented in Greek art with great frequency. However, Herakles' role and representation in the event is limited. The themes of the Giantomachy are canonical and nearly identical to other mythological wars (e.g., Amazonomachy, Titanomachy, Centauromachy): they represent the confrontation between the civillized and the savage, reason and chaos, justice and injustice, Greek and barbarian. The Giantomachy was not, however, centered on Herakles. Rather, he took part in the battle. It was primarily a war between the Olympian gods and the Giants (children of Gaia). As such, visual narratives do not generally feature Herakles but, rather, the Olympians themselves. They are often as likely to highlight the martial exploits of Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Poseidon, etc., because, like Herakles, they all have their parts to play and their particular Giants to slay in the various narratives surrounding the Giantomachy.

The Giantomachy is interesting from the limited perspective of its relation to the kleos (glory, fame) of Herakles in the same way that retrieving Kerberos, the watch dog of Hades was: it foreshadows the hero's eventual apotheosis (deification), conquest over death, or transcendance of mortality as the lone mortal who fought beside the gods. Apollodorus is the most detailed surviving textual source for the event:

Ge [Gaia, "Earth"], angry about what happened to the Titans, produced the Giants by Ouranos, unsurpassed in bodily size, in power unconquerable. They looked frightful in countenance, with thick hair hanging from their heads and chins, and they had serpent coils for legs. According to some they were born in Phlegrai, but according to others in Pallene. They hurled rocks and flaming trees into heaven. Greatest of them all were Porphyrion and Alcyoneus. Alcyoneus was immortal as long as he fought in the same land where he was born, and he even drove the cattle of Helios out of Erytheia. It had been prophesied to the gods that none of the Giants could be killed by gods, but that if a certain mortal fought as their ally, the Giants would die. When Ge learned of this, she sought a magic herb to prevent them from being killed even by a mortal, but Zeus forbade Eos [Dawn], Selene [Moon], and Helios [Sun] to shine. Then he himself cut the herb before Ge could and had Athena call Heracles to help them as an ally. [9]

So it was that Herakles was brought into the war between Olympians and Giants because of a prophecy that the Olympians would only be victorious if a mortal fought on their side (the specifics surrounding the mortal and his role vary in the telling). In all (known) cases, however, that mortal is Herakles, and the giant he faces off with is usually Alcyoneus as in the excerpt from Apollodorus (above). However, earlier sources describe Herakles fighting Alcyoneus independent of any larger context such as a war with the Olympians. In Pindar (5th century BCE), the context of their fight is simply over the theft of the cattle of Helios, and the giant is caught napping when he is slain. The circumstances surrounding Alcyoneus' invulnerabilty are strikingly similar to those of Antaios, the giant whom Herakles defeated in Libya while seeking the apples of the Hesperides. It's possible, if not probable, that the inclusion of Herakles in the Giantomachy is a late addition to the hero's mythololgical corpus, perhaps with an eye toward reaffirming or foreshadowing his eventual ascention to Olympos after his death.

Attic red-figure volute krater attributed to Kleophrades Painter (c. 480-470 BCE). Getty 84.AE.974.

Herakles, backed by Athena, approaches a sleeping Alkyoneus surrounded by the stolen cattle with a miniature Hypnos (Sleep) resting on his chest. The giant also weilds a club depicted similarly to that of Herakles. Iolas drives off the cattle to the left.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

(CC BY-NCPSA 4.0), background removed.

Attic black-figure amphora by Lysippides Painter (c. 520-500 BCE). British Museum 1839.1109.3.

"Gigantomachia: In the centre a quadriga to right, the third horse white, the others black; Zeus is stepping into the chariot and holds the reins in left hand, while brandishing a thunderbolt in right; he is bearded, and wears a short striped embroidered chiton and cuirass. In the chariot is Heracles, on the further side of Zeus, with left foot put forward on the pole; he wears a short embroidered chiton and the lion's skin, with quiver at his back, hung from a cross-belt, and is in the act of shooting an arrow from his bow. At the further side of the quadriga is Athene to right, with long tresses, high-crested helmet, long diapered chiton, the patterns partly incised, partly painted, aegis with fringe of snakes, and purple breastplate, probably for the Gorgoneion, shield with device of a tripod; she thrusts with spear at a fallen giant (probably Enkelados). Three giants (Enkelados, Hyperbios, and Ephialtes) are opposed to the deities."

[1] Trzaskoma, Stephen M.; Smith, R. Scott. Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology (Hackett Classics) . Hackett Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid

[4] Ctrl+x (cut) and ctrl+v (paste) if you were wondering. And no. Achaeological evidence suggests that the Library of Apollodorus was not composed on a Windows-based computer but on a Tandy from Radio Shack (editorial note: Radio Shack was a electronics store and the home to a pre-Microsoft and pre-Apple world with computers. I know, right? It was the stone age. The savages!

[5] Ganymede was the archetype for beautiful boys and represented the idealized male youth famous on kalos cups that older men would offer to their youthful male objects of affection at Athens (among other poleis?). The Trojan line is populated with attractive males in their lineage: Ganymede was raped by Zeus and brought to Olympos as Zeus' cup bearer (think "pool boy" but pouring drinks instead of cleaning pools); Anchises was a mortal lover of Aphrodite, Tithonos (Laomedon's son) became the consort of Eos (Dawn); and Paris rather famously seduced Helen, then of Sparta, making her Helen of Troy!

[6] Trzaskoma, Stephen M.; Smith, R. Scott. Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology (Hackett Classics) . Hackett Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[7] Stafford, Emma. Herakles. Gods and Monsters of the Ancient World. Routledge (2012).

[8] Trzaskoma, Stephen M.; Smith, R. Scott. Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology (Hackett Classics) . Hackett Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[9] ibid.