Right: Attic red-figure kylix attributed to Douris (c. 480-470 BCE). Vatican Museums 16545.

Photo: Daderot (wikimedia).

Jason being rescued by Athena from the dragon while attempting to steal the golden fleece (hanging atop tree in background).

The themes and motifs in myths surrounding Jason and the Argonauts are familiar in form and function. They follow a nearly identical trajectory as those of Theseus, Bellerophon, Perseus, and Herakles:

These “steps” on the hero’s journey reflect the more mundane cycle of life for everyday humans: life is hard. We struggle to survive. Bad things happen to good people and vice versa. The best of us die. It is part and parcel with being mortal. These facts dominate mythological thinking, and they also occupy a great deal of modern philosophy. After all, we humans are still mortal. We still suffer the seemingly random or chaotic whims of fate, nature, or (corrupt) persons who exert power over us. No matter how glorious or successful our careers are, they rise, peak, and fall. We grow old, lose the vitality that made us great, and eventually die.

Let us end this introduction by analyzing two popular movie quotes; neither idea is particularly unique to the movie it is quoted from, but I like the movies, so I'll jump at any chance to reference them! :-)

“Life is pain, highness. Anyone who tells you different is selling something.”

(Westley, Princess Bride, 1987)

“Ultimately, we’re all dead men. Sadly we cannot choose how, but we can decide how we meet that end in order that we are remembered as men.”

(Proximo, Gladiator, 2000)

Of the former, little is left to say. To exist is, in a sense, to suffer. Suffering is an inescapable aspect of life. The Five Ages of Man in Hesiod and the myth of Pandora convey the same message: the gods, Zeus chief among them, have so ordered human life that it is a struggle. Humans in the Iron Age suffer. Men manipulated or beguiled by Pandora find themselves in a world teeming with evils and danger. Likewise, Herakles, Perseus, Theseus, and Jason experience tragedy, disaster, and loss.

The Gladiator quote speaks directly to the anthropological function of muthoi (stories): muthoi live on long after the persons in them are dust and ashes. The only way a mortal survives is in living memory (i.e., the memory of those people still alive). We have dedicated a lot of time this semester to analyzing the ways in which myths affirm or perpetuate cultural norms and mores (e.g., the way gender expectations are modeled in the Long Homeric Hymn to Demeter). But myths also perpetuate the equally powerful idea that death, no matter how inevitable or final it is for mortals, can be overcome, or at least tempered, by keeping the memory of one’s deeds, one’s identity, alive in the stories that are told about him/her. As Proximo says, everybody dies. We cannot escape that fate. But we can affect how we are remembered so that some part of us survives – and that it is an admirable part! Thus, it is not the miserable end to many of our heroes’ lives that matters most. Death is simply a function of being human – human life is ephemeral and death inevitable. What matters is 1.) that we’re remembered, and 2.) how we are remembered (i.e., remembered in a positive light).

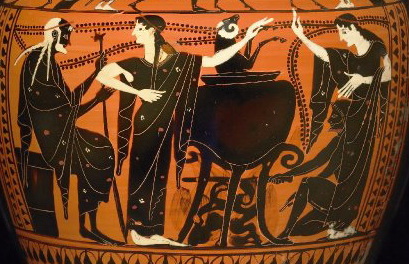

Red-figure column-krater attributed to the Orchard Painter (c. 470-460 BCE). Met 34.11.7.

Jason, portrayed nude, reaches for the golden fleece that hangs from a large tree at left. Athena stands at center, directing and looking over the hero. At right, one of the Argonauts stands at the prow of the Argo, waiting for Jason to return with the fleece.

Perseus’ signature adventure to retrieve the head of a gorgon was a quest for a magical token. Herakles was assigned tasks to retrieve numerous items, but the Apples of the Hesperides or Kerberos (the hound of Hades) are probably the most outlandish. Theseus’ career began by obtaining tokens (sandals and a sword), and he set out to free Athens from the yoke of Cretan tyranny by slaying the Minotaur. Yet no adventure in the canon of Greek myth typifies the hero’s quest more than Jason’s pursuit of the golden fleece. The hero sets out on an impossible task to retrieve a magical token guarded by a man-eating “dragon”[1] to save his loved ones from an evil fate.

Having already studied the myth of Perseus and Medusa, the contrivance that begins Jason’s quest should seem very familiar. They are, at least in Apollodorus’ version, virtually identical:

When Pelias caught sight of [Jason], he connected him with the oracle, approached him, and asked what he would do if he were the ruler and received an oracle saying that he would be killed by one of his citizens. Jason [...] said, “I would command him to bring the Golden Fleece.” When Pelias heard this, he immediately ordered him to go after the Fleece, which was in a grove of Ares in Colchis, hanging from an oak tree and guarded by a serpent that never slept.

Colchis was located beyond the Greek world in the Black Sea area of Asia. Thus, the people of Colchis were non-Greeks, what Greeks referred to as barbarians. Although it is a term for non-Greek speakers, it included all of the same derogatory connotations in Greek as it does in modern English. To be a barbarian was to be uncivilized, savage – something less than Greek. True to form, the king of Colchis, Aietes, was a crooked ruler. He agreed to give Jason the fleece, but only if the hero could accomplish the impossible task of subduing a magically imbued bull and then sowing the seeds of a dragon that would, unbeknownst to the hero, spring forth armored warriors ready to kill him. Failing that, Aietes had expected the dragon itself to slay the hero. Apollodorus describes it thusly:

As was the case with Perseus and Herakles, the hero did not simply set out for the fleece, confront the mythological monster, and return triumphantly home. He was ill-equipped to do so. Rather, he gathered men, resources, and tokens of power that he would use to achieve his goal. The aide of a divine helper, most often Athena, is the first such resource. Indeed, without the favor of Zeus (or Athena who represents the will of Zeus), no hero could hope to succeed. Perseus required winged sandals, the kibisis, Athena’s advice, etc. to behead Medusa. Herakles did not simply walk into the underworld and drag Kerberos back kicking and screaming; he grew in strength and power, acquiring the impenetrable hide of the Nemean lion and arrows dipped in the poisonous blood of the hydra. Jason received advice from Athena, the shipwright Argo, the magical guidance of the Dodona tree, and the aide of a cadre of the Greek world’s most famous living heroes (including Herakles himself!). Many of the heroes Apollodorus names are famous fathers of heroes from the Trojan War, children of Olympians, and heroes from other heroic myths. Jason assembles the equivalent of an all-star or “Dream Team” to retrieve the golden fleece.

Explaining what he had been ordered to do by Pelias, [Jason] asked Aietes to give him the Fleece. Aietes promised to give it to him if Jason would yoke his bronze-footed bulls by himself [...]. He ordered Jason to yoke them and then plant teeth form a serpent; he had gotten form Athena the other half of the teeth that Cadmos had planted at Thebes.

Any one of these plans would have succeed in killing Jason had it not been for Medea. Medea has much in common with Ariadne in Theseus’ quest against the Minotaur. She was a foreign princess who fell in love with the hero and lent him her aide in return for his romantic affection. Apollodorus continues:

While Jason was at a loss as to how he might be able to yoke the bulls, Medeia fell in love with him. She was the daughter of Aietes and Eidyia daughter of Oceanos. She was also a sorceress. Afraid that he would be destroyed by the bulls, she, unbeknownst to her father, promised to help Jason with yoking the bulls and to get the Fleece into his hands if he would take her as his wife to Greece as his companion on the voyage.

Thus, Jason secured the aide of Medea. In one interesting version of the myth, Medea aides Jason in his escape from Aietes, who had sent his entire fleet after the Argonauts, by kidnapping one of her brothers, slaying him, and then throwing parts of his corpse into the sea at different intervals. This tactic delayed their pursuers as Aietes needed to stop and collect each piece of his child so that he could properly bury him. To go unburied was the ultimate taboo in the Greek world, because the deceased person’s soul would not be permitted to cross the river Acheron (or Styx)[2] and enter the house of Hades where all the dead called home. However, the horrific act of fratricide brought down a curse of blood-guilt on Medea. She murdered her own brother. She betrayed her family by siding with Jason, allowing her emotional whims to overrule her rational mind. These were all stereotypical traits of females and barbarians. It was Medea who was responsible for the horrific butchery of Pelias, himself a crooked ruler, at the hands of his own daughters. This crime was enough to result in the banishment of Jason and Medea from his homeland in Iolcos.

The relationship between Jason and Medea soured rather famously after they fled Iolcos and made a home in Corinth. These events were dramatized in the surviving 5th century Attic tragedy Medea by Euripides. In the play, Jason has had children with Medea while the two live in Corinth, exiled from his homeland of Iolcos. But Jason has befriended the king of Corinth, Creon, and the two negotiated a marriage between Creon’s daughter and Jason just before events of the play unfold. Thus, Jason attempts to push Medea, his barbarian consort, aside, and marry into a more “civilized” union with the proper Greek princess of Corinth, Glauke.

This pattern repeats itself in numerous heroic myths. We have seen Theseus abandon Ariadne once she aided him in escaping the labyrinth of the Minotaur. Herakles, in the final event of his long-lived career, attempted to replace his wife, Deianira, with a younger princess, Iole. Although Herakles’ two women were both Greek, the resulting debacle of that abandonment parallels the eventual outcome for Jason very closely. It cost Herakles his life, just as Jason’s attempt to brush aside the sorceress Medea cost him the lives of his children, his wife-to-be in Glauke, and his father-in-law-to-be in Creon.

Medea, already proven to be a savage barbarian by her betrayal of her father, butchery of her brother, and deceitful dealings with the daughters of Pelias, commits the ultimate taboo for a mother in Greek culture: infanticide. Once again, Greek views of women and barbarians are reinforced by the horrific actions of Medea. Meanwhile Jason, the hero who assembled the Greek world’s mightiest heroes, lived out the remainder of his days a bitter, broken man without heirs to inherit his name.

Apollodorus’ version of events is not so misogynistic as those of Euripides’ play. According to him, it is the people of Corinth who act savagely and vengefully in murdering the infant children of Medea and Jason:

From Helios she got a chariot that was pulled by winged serpents and made her escape to Athens on it. It is also said that when she fled, she left behind her sons, who were still infants, setting them on the altar of Hera Acraia as suppliants. The Corinthians took them out of the sanctuary and wounded them fatally.

Attic black-figure hydria attributed to the Leagros Group (c. 510-500 BCE). British Museum 1843,1103.59

Medea is shown tricking Pelias and his daughters by having boiled an old ram in a pot, and then the ram emerged a youthful lamb. Pelias' daughters witnessed this miraculous transformation and convined Pelias to undergo the same process. He was boiled in the cauldron but did not emerge youthful...or at all.

"On the right is Medea to right looking to left, waving her arms over the lebes; by her side is Jason kneeling to left, nude and bearded, placing a log on the fire. On the other side of the lebes is one of Pelias' daughters to right, looking back at him with left hand extended; she and Medea both have long hair, fillets, and long chitons and himatia, both embroidered. On the left is Pelias seated to right, with white beard and long tresses with fillet, wrapped in an embroidered himation, sceptre in left hand. In the field, branches" (British Museum).

© The Trustees of the British Museum

(CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This painting is of particular interest to the study of the myth because it depicts Jason as unequivocally implicit in the crime of (ultimately) murdering Pelias. He is shown here tending the fire that will be used to boil Pelias to death.

The core elements of the scene as it appears on other black- and red-figure paintings are the daughters of Pelias, the lebes (cauldron) with either a ram or lamb, Medea, and Pelias. This is the second of three horrific acts of familial violence that are attributed to Medea in Archaic and Classical art and literature. It is the most common in surviving Archaic and Classic narrative art.

Medea’s decision to leave her sons behind may be viewed as abandonment and thus debased, but she also goes out of her way to leave them in a safe place, suppliants in the sanctuary of a god – with the pointed irony of that god being Hera, in the Heraion Akria. The very idea that they were suppliants at the sanctuary of any god would make harming them an act of hubris (spiritual outrage) like the crime of murdering a guest-friend under the protection of xenia. Hera and Medea find themselves in similar roles throughout Greek mythology: they are both humiliated by their respective husbands’ affairs, and both affronted wives actively[3] maneuver to avenge themselves, either on their husbands, husband’s lovers, or the children that result from the affairs (e.g., Herakles, Semele, Jason, et al.). Indeed, Hera’s province is to oversee the bonds of matrimony and, not coincidentally, is a goddess of women in general. Once again, this is no coincidence; women were largely defined by their role as wives in Greek culture.[4]

Medea’s most horrific act, that of murdering her own children, was not part of Apollodorus’ story. Rather, the mythographer tells us that she fled to Athens on a dragon-drawn chariot and made a home there with Aegeus, the king.[5] Having already studied the myth of Theseus, we saw that she tricked Aegeus into contriving to kill his own son by completing the impossible task of subduing the Cretan bull:

Medeia made it to Athens. There she married Aigeus and bore him a son, Medos. later, she plotted against Theseus and was driven into exile from Athens with her son. But her son conquered many barbarians and called the whole area under his control Media.

Lucanian red-figure kalyx-krater by Policoro Painter (c. 400 BCE). Cleveland 1991.1

"The remarkable scene on the front of this vase relates to the famous tragedy Medea, written by Euripides and first produced in Athens in 431 BC. Framed in the center by a halo (recalling her sun god grandfather Helios), the sorceress Medea flies off in a dragon-drawn chariot. Seeking revenge against her husband Jason, leader of the Argonauts, Medea has just slain their two children. Two Furies flank her, while Jason and a distraught nurse and teacher approach the bodies on the altar below."

The demonization of Medea across various iterations of her story is quite amazing: 1) She betrayed her familial bonds by aiding Jason in his pursuit of the golden fleece; 2) She cut her brother into pieces and dropped the pieces into the sea to facilitate Jason's escape from Colchis; 3) She manipulated the Daughters of Pelias into cutting their own father to pieces and boiling him in a cauldron; and 4) She slew her own children out of rage and to spite Jason who had set her aside for a "better" marriage prospect. In each of these horrific acts, Medea's status as a barbarian and irrational/overly emotional woman are emphasized or suggested as explanations for her savage deeds.

This final episode from Apollodorus is an aetiological explanation for the origins of the Persian empire and the enmity between Persia, an Asiatic empire, and the Greeks, a European people. In this version, the people who would eventually merge with and become the Persians and then attempt to conquer all the Greek world were the descendants of Medea, a mythological figure of Asiatic barbarism. This mythological link between barbarism and peoples of the Near East is highlighted in the demonizing of Amazons and the myth of the rape of Helen, perpetrated by an Asiatic Trojan prince that led directly to the Trojan War. The Trojan War was viewed by the Greeks as an antecedent to the Persian wars that inflamed the eastern Mediterranean in the first quarter of the 5th century BCE.

[1] The term drakkon in Greek, dracon in Latin, generally refers to a large serpent rather than the 2-4-legged beast that dominates northern European conceptions.

[2] Both are cited as the river across which Charon ferries the dead according to different sources.

[3] Proper females (i.e., those who conform to dominant gender roles) are expected to be passive in Greek and many cultures. This is one of the reasons Amazons were held-up as abominations in Greek myths.

[4] Hera. Theoi.com.

[5] See “Jason and Medea at Corinth,” inset below.