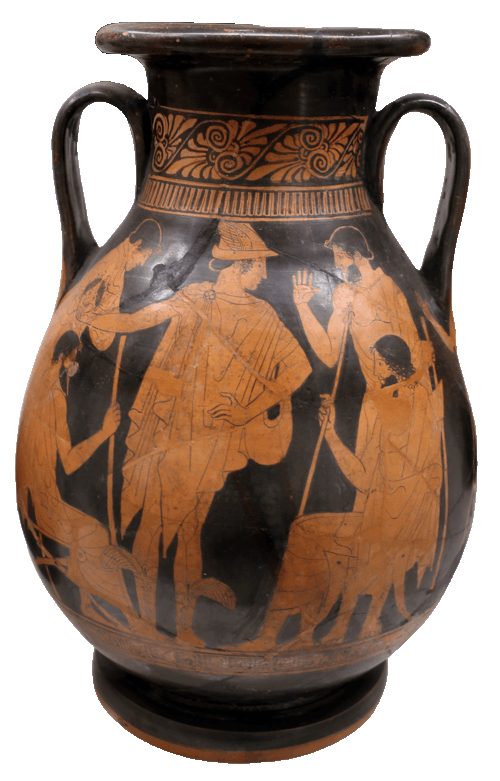

Left: Campanian bail-amphora attributed to the Ixion Painter (c. 330-310 BCE). MET 06.1021.240

Bellerophon astride Pegasos battles the Chimera.

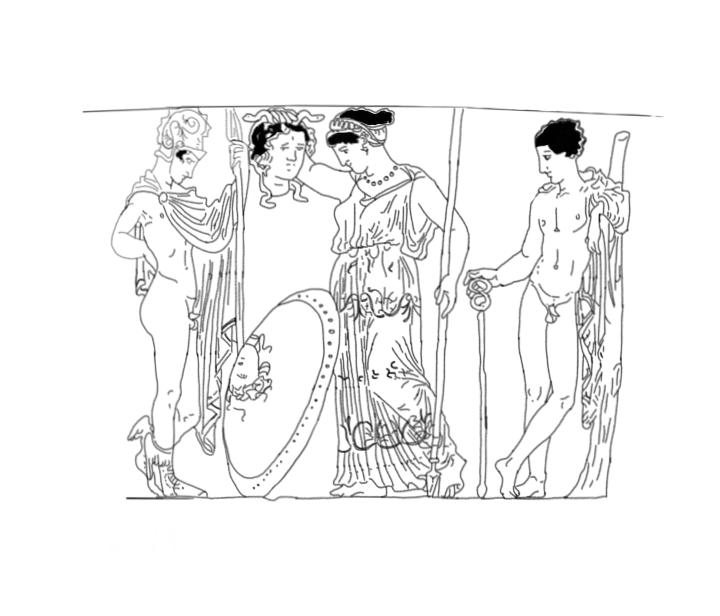

Right: Drawing of scene on bell krater by the Tarporley Painter (c. 400-385 BCE). Boston MFA 1970.237.

Perseus, Athena, and Hermes contemplate the reflection of Medusa's face in a shield.

This series of essays on Greek heroes is introductory in nature and relies largely on the mythographies attributed to Apollodorus (Library of Apollodorus) and Hyginus (Fabulae).

As is the case in all articles on this site, the ancient art surrounding these myths serve as individidual versions in their own right that are used to inform our understanding of the heroes and their stories.

Perseus and Bellerophon are bound together in the modern psyche because of their relationship to the winged horse Pegasus and the popularity of 20th Century movies surrounding Perseus (i.e., the various iterations of Clash of the Titans). In those movies, Perseus tames and rides the winged horse on his adventures to slay Medusa and wage battle against other threats to human civilization – be they monsters or titans! The ancient myths share similar themes – the hero as champion of civilization who slays the monstrous threats to humanity – but the particulars of the two heroes are rather different and have been fused in modern stories of their exploits. In short, Perseus was directly involved in the genesis of Pegasus, but Bellerophon was the Greek hero who gained fame for taming and flying the winged mount.

In this essay, we will examine themes and motifs of the surviving textual and visual narratives surrounding these two early heroes. Our primary textual source for Perseus is the relatively late mythographer from 2nd Century CE Greece, Apollodorus, and both Apollodorus and Homer (8th Century BCE) provide extant textual narratives for Bellerophon. These textual sources are supplemented by surviving visual art that dates as far back as the early 7th century BCE through the Imperial Roman period (4th Century CE).

Perseus is loosely regarded as the earliest hero in Greek myth, meaning his adventures occur chronologically before those of the other heroes in the klea andrōn (hero tales).[1] As the term “loosely” suggests, Perseus’ adventures may not always occur before those of other heroes, and there is great variability between each iteration of the myth:

The imposition of chronology on the generations of heroes is an unstable business at best. However, by most accounts Perseus is one of the earliest – three generations removed from Herakles, the greatest of Greek heroes, who was himself a generation removed from the heroes of the Trojan war. Perseus is also one of the earliest mythological figures to appear in Greek narrative art, in his beheading of Medusa.[2] Other parts of the Perseus story are shown primarily in 5th- and 4th-century art.[3]

In addition to the loose chronological association between mythical figures and the chronology of their adventures, the fact that Perseus is viewed as the first hero of Greek myth does not necessarily mean he was the first hero whose story was told in myth. For example, the god Dionysos was worshiped as a new, young god in the Greek pantheon. Many of his myths center around the arrival of the god to an already established hierarchy amongst gods and humans. He is portrayed not only as a young god (child of Zeus), but as a god newly arrived on Olympus and to human worship. Yet Dionysos enjoys the prestige of being one of the earliest gods appearing in Greek texts. Worship of Dionysos is attested on Linear B tablets from Mycenean palaces, inhabitants of the Greek mainland and Aegean islands from about 1600 BCE to 1100 BCE. In other words, despite the fact that a mythological figure is depicted as “new,” or “young” in the various stories surrounding him, his presence within the culture’s mythological consciousness could be attested long before other, “older” figures.

Thus, to call Dionysos a “new god” or Perseus an “old hero” is complicated. We can speak of a chronology of heroes and gods within the stories themselves, or we can speak of chronology of sources (i.e., which myth occurred first in the historical record). The former is dangerous because even the same source (e.g., Hesiod) contradicts, alters, or amends its stories from one myth to another, sometimes within the same poem (try reconciling the creation of Pandora with the Five Ages of Mankind in Hesiod’s Works and Days). The latter is fraught with uncertainty because there is no telling what works are lost vs. those that survive today. Perhaps the oldest narrative text is the Iliad, and the story of Bellerophon is narrated in that work, but was that really the first version of the Bellerophon story? Almost certainly not. Or is it simply the oldest surviving version of the Bellerophon myth? Almost certainly so. In such a case, how can we know whose story was told first? Ultimately, each version of the myth is its own authority.

Athenian Proto-Geometric vase (c. 675-650 BCE).

Archaeological Museum of Eleusis. LIMC Gorgones 312.

Image: Sarah Murray. (CC BY-SA 2.0) backround removed.

The scene only partially survives on the body of an Athenian Proto-Geometric vase from the first half of the 7th century, making it one of the earliest surviving, identifiable scenes in Greek vase painting.

From this angle, Medusa's gorgon sisters can be seen pursuing a man (only legs are visible) with a female figure holding a spear between the man and the gorgons, facing the sisters. Behind the two gorgons (not visible) is a third figure of identical design laying horizontally without a head. Click the image for a closer look!

Positively identifying scenes from Greek myth is rare in Greek art before the advent of black-figure. This is due in part to two reasons. First, mythological art and figural art in general is rare in geometric vis-à-vis later periods. Secondly, the practice of labeling figures was common on black- and red-figure vase painting. It was significantly less so on earlier forms of painting.

The latter issue is compounded by the fact that one must recognize the identity of figures and the activities they’re engaged in within the painting, but in order to do that, one must already know the story that the visual medium narrates. Thus, while it’s likely that the visual narrative existed before the textual one, we rely on the later textual narrative to identify the visual ones.

In this painting, for example, we know who Perseus is, that he slew Medusa, was aided by Athena, and narrowly escaped the other gorgons, because it was recorded textually, either as transcriptions of songs, Roman (written) poetry, or mythographers. We then take what we’ve gleaned from these later sources (Apollodorus in this case) and identify visual representations that appear to agree with what the later text tells us about the event. If the unlabeled geometric or protoblack-figure art differs very much from the later mythographer, then the visual narrative could go unidentified. There are numerous figural depictions of warriors in procession or marching to war as well as funerary scenes depicted in geometric art, but without any further context, we are unable to identify them as scenes from myth or mundane everyday ritual/practice.

Indeed, there exists a tantalizing signet ring from the Mycenaean period [5a] that my represent the first narrative representation of the rape of Helen, but without much greater context or contemporary textual evidence, identifying that sculpture with any degree of certainty is necessarily an exercise in wishful thinking.

The circumstances surrounding Perseus’ conception are representative of those of the klea andrōn throughout Greek myth and, in fact, are recognizable in the fantastical metamorphoses or “transformation” tales of western Europe. From an anthropological perspective, these myths serve a few familiar functions:

First, they establish principles of right and wrong centered around the violation of one taboo or another.[4] We saw this in the creation and succession myths surrounding Ouranos, Kronos, and finally the establishment of a just and ordered cosmos under Zeus in Hesiod’s Theogony.

Second, these origin stories, in fact, all of the klea andrōn without exception, reinforce an immutable law in the Greek world regarding the relationship between humans and gods: humans live in ignorance while the gods enjoy access to absolute truth, and this is where we will begin our analysis of the circumstances surrounding Perseus’ birth: a visit to an oracle.

Third, these tales entertain. The more memorable aspects of such episodes involve the miraculous nature of the heroes' conceptions or seductions themselves, often intertwined with the violation of cultural taboos, as is the case for Perseus’ own conception. The gods (usually Zeus) go to great and memorable lengths to impregnate their mortal lovers. Zeus transforms into a swan to impregnate Leda; he turns his lover, Io, into a cow to hide her from Hera’s vengeance; he steals Europa away by taking the form of a bull; he grants a wish to Semele like Aladdin’s Genie; and he transforms himself into droplets of golden light/rain to impregnate Perseus’ mother, Danae.

Perseus’ story begins with his grandfather, the king of Argos, who was desperate for a male heir, so he consulted an oracle:

Akrisios, King of Argos, received an oracle that his daughter would give birth to a son who would kill him. In an attempt to protect himself and avoid his fate, he locked his daughter, Danae, in an underground chamber of bronze to keep her from men. Zeus, however, had fallen in love with her and came to her as a golden rain that streamed down from the roof of her chamber. From this union Perseus was born. [5]

We can already note the three functions of heroic myth manifest themselves in Apollodorus’ summary of this myth (he mentions another involving Proitos[6]): Acrisios unjustly imprisons his daughter, a deed reminiscent of Ouranos imprisoning his children and Kronos devouring his. The ignorance of mortals and their impotence in the face of fate (or the gods) is affirmed by Zeus easily circumventing Acrisios’ best efforts to maintain his daughter’s chastity. Finally, Zeus circumvents Acrisios’ safeguards in a fantastical and unique manner – golden rain in this telling – that the event is more easily remembered and distinguished from other, standard forms of conception. These three basic principles will recur throughout Perseus’ heroic career.

Acrisios’ violation of taboos continues once he realizes that Danae is pregnant:

When Acrisios later learned that she had given birth to Perseus, he refused to believe that she had been seduced by Zeus and so put his daughter and her child into a chest and cast it into the sea.

Attic red-figure lekythos (c. 5th century BCE).

Danae and the young Perseus float at sea in the box ordered made by Akrisios to expose the pair. Sea birds fly in the sky above them.

Popular vase paintings of the construction of the box exist in the collections of the Boston MFA and Toledo Museum of Art respectively:

Red-figure lekythos (c. 470 BCE), Toledo 1969.369.

This action gives rise to a brief discussion on Greek practices of exposure and infanticide. There is little or no evidence that exposure (a kind of infanticide) and human sacrifice were remotely common from the archaic period onward (i.e., when we recognize the Greek world as being quintessentially “Greek”). Yet they occur regularly throughout Greek myth. They do so as taboos and expressions of unbridled (unconscious?) fantasy.

Infanticide is killing children, one’s own child in most cases. It is a cultural taboo alongside other forms of kin-killing such as patricide (killing one’s father), matricide (killing one’s mother), and fratricide (killing one’s sibling). Exposure is a ritualized form of ridding oneself of an unwanted child and is intended to circumvent the negative spiritual taint of infanticide. By “exposing” a child to nature, such as carrying the newborn into the mountains and leaving him there to die to wild animals, starvation or the elements, the offending parent spares himself the taint of literally spilling the blood of his own child. Acrisios exposes both Danae and Perseus in his own way: setting them adrift in a chest at sea with no hope for shelter and sustenance.

Of course, these myths are charters of social norms and customs. Ouranos and Kronos paid a hefty price for their transgressions, and the mortal Acrisios certainly will as well, but not for years to come, when he is inadvertently slain by Perseus while competing in an athletic competition (either a javelin or discus throw). In the meantime, Danae and her baby Perseus are rescued by the fisherman Dictys, who takes them to his home on the island of Seriphos where Perseus will spend his youth.

Perseus’ most famous exploit was slaying the gorgon Medusa, an exploit he achieved only with the aid of numerous supernatural helpers. Interestingly enough, the moral core that begins this leg of Perseus’ life is very similar to that of the Acrisios episode. According to Apollodorus,

Dictys’ brother Polydectes, who was king of Seriphos, fell in love with Danae, but since Perseus had in the meantime grown to manhood, he was unable to sleep with her. So he called his friends together – and Perseus too – and told them that he was trying to collect contributions so that he could marry Hippodameia daughter Oinomaos. Perseus said that he would not refuse even to give the head of the Gorgon, so Polydectes asked for horses from everybody else, and when he did not get horses from Perseus, he ordered him to bring the Gorgon’s head. [7]

Polydectes proves himself to be a corrupt monarch. His

carnal desire for Danae makes him unscrupulous, and he tricks Perseus into taking

on an impossible task. This charge of a seemingly impossible task is a common

feature of heroic literature and a staple of the Greek heroic myths. [8]

Attic red-figure pelike attributed to Polygnotos (c. 450-440 BCE). MET 45.11.1.

Perseus in the process of decapitating the gorgon Medusa while Athena looks on. The artist is careful to paint Perseus turning away from Medusa to avoid eye contact. He wears the winged sandals given to him by the nymphs (according to Apollodorus) and uses a harpē [8] to sever the gorgon's head.

Note that the aegis of Zeus on Athena is absent the signature gorgoneion. Perseus will give Medusa's head over to Athena once he has completed his quest to bring it before Polydektes, and she will then sew the head into the magic garment.

The hero wears a winged hat. It's not entirely clear if that is the helm of Hades or another connection to flight. It is as common for Hermes to be depicted with such a winged helm (instead of petasos) as it is for him to wear the winged footwar. As for Perseus, he is variously depicted with a petasos, winged helm, without headgear, or with a Phrygian cap.

Attic black-figure dinos by the Gorgon Painter (c. 600-590 BCE). Louvre E 874. Shonagon (CC0 1.0).

Two winged Gorgons with monstrous faces pursue Perseus, who runs toward an awaiting chariot. The headless body of Medusa is still falling over behind her two sisters. The following angle linked below shows the three Gorgons and part of Perseus: Louvre E 874 (Classical Art Research Centre).

Apollodorus doesn’t provide great detail as to exactly how Athena and Hermes aide the young hero, but as a general rule, gods give direction (knowledge). What we do know is that after tricking the Graiai (witches and sisters of the Gorgons) into revealing how he might slay Medusa (the only mortal Gorgon), Perseus made his way to the “Nymphs.” These are presumably either the fifty famous daughters of Nereus (Nereids) or generic fresh water nymphs (Naiads):

These Nymphs had winged sandals and the kibisis, which they say was a pouch. They also had Hades’ cap.

The kibisis, sandals, “cap” (Hades’ helmet), and the adamantine sickle acquired from Hermes, are all supernatural tokens that the hero collects to aid him along his journey. One would liken them to new armor or trinkets in a modern RPG game that give the hero or player higher level abilities, which are necessary to succeed in the increasingly more difficult tasks that he will undertake. With the winged sandals, Perseus is able to fly to the abode of the Gorgons, a place otherwise inaccessible to flightless mortals. Wearing Hades’ helmet, Perseus is able to sneak past the sleeping Gorgons to come upon the only mortal of them, Medusa. With Hermes’ sickle, Perseus can decapitate Medusa, and the kibisis is a sack with magical properties that enable him to carry the dangerous head of the Gorgon. Finally, with Athena’s advice, Perseus avoids eye contact with Medusa, whose sight would turn him to stone.

Corinthian black-figure amphora from Cervetri (c. 560 BCE). Altes Museum, Berlin.

Perseus and Andromeda. Perseus, wearing his hat and winged boots, and with the kibisis over his shoulder, throws rocks at a ketos (sea monster) while Andromeda stands behind him. A very similar event and painting occurs in Herakles' adventures near Troy. Note that Perseus does not utilize the head of Medusa in defeating the ketos.

On his way home from the Gorgons, who lived at the proverbial end of the earth, Perseus flew over Ethiopia:

Arriving in Ethiopia, where Cepheus was king, he found the king’s daughter Andromeda set out as food for a sea monster. Cassiepeia, the wife of Cepheus, had vied with the Nereids over beauty, boasting that she was superior to all of them.

Yet again, we find humans in a difficult situation because they transgressed a fundamental boundary between gods and humans: Cassiopeia boasted that her daughters were more beautiful that the Nereids, nymphs or minor goddesses of the sea. Cassiopeia failed to know or acknowledge her place. Perhaps she did not violate a more obvious taboo such as infanticide, but she certainly crossed a line by placing her daughter, a mortal, above immortals goddesses. A similar situation famously arises in Book 5 of the Odyssey in which the nymph Calypso compares herself to Odysseus’ mortal wife, Penelope:

“Son of Laertes in the line of Zeus, my wily Odysseus,

Do you really want to go home to your beloved country

Right away? Now? Well, you still have my blessings.

But if you had any idea of all the pain

You’re destined to suffer before getting home,

You’d stay here with me, deathless –

Think of it, Odysseus! – no matter how much

You missed your wife and wanted to see her again.

You spend all your daylight hours yearning for her.

I don’t mind saying she’s not my equal

In beauty, no matter how you measure it.

Mortal beauty cannot compare with immortal.”

Odysseus, always thinking, answered her this way:

“Goddess and mistress, don’t be angry with me.

I know very well that Penelope,

For all her virtues, would pale beside you.

She’s only human, and you are a goddess,

Eternally young.” [9]

Odysseus was famous for knowing his place and not aspiring to be more than the mortal that he was. Cassiopeia, in placing her daughter’s beauty above that of the Nereids, does precisely the opposite. Were it not for Perseus’ intervention, she would find herself another Niobe, a woman who bragged that she was a better mother than Leto. For while Leto raised two perfect children (Artemis and Apollo), Niobe raised seven sons and seven daughters that she held to be superior to all other mortals, thus making her a better mother. Artemis and Apollo slew all of Niobe’s children for her hubris (outrage), and she turned to stone that weeps when the snow melts above it.

In any case, Apollodorus continues the story of Perseus, as he flies over Ethiopia to see a beautiful young woman chained to the rocks near the surf:

When Perseus saw [Andromeda], he fell in love. He promised Cepheus that he would destroy the monster if he would give him the girl to marry after she had been rescued. Oaths were sworn on these terms, and then Perseus faced the monster, killed it, and freed Andromeda.

A very similar story is told about Herakles, while on his way to the Amazons in the depths of Asia; the hero came across a princess chained to a rock as a sacrifice to a sea monster. Herakles struck a deal with her father, the king of Troy, rescuing the princess and slaying the monster. Although not in love with the princess (Herakles bargained for horses as payment), the basic plot points are strikingly similar.

New wife in hand, one of many “trophy wives” in heroic literature, Perseus returned to Seriphos:

When he came to Seriphos and found that his mother had taken refuge with Dictys at the altars because of Polydectes’ violence, he went into the palace. After Polydectes had summoned his friends, Perseus turned away and showed them the Gorgon’s head.

Attic red-figure pelike attributed to Hermonax (c. 470-460 BCE). (Beazley CN: 205408)

Perseus and Polydektes in the court of Polydektes on Seriphos. Perseus holds up the head of Medusa. Note Perseus' face is turned away from the head in his outstretched hand while all other eyes are toward the gorgon's head.

Photo credit: Saiko (CC BY-SA 4.0). background removed.

Perseus returns triumphant from his impossible task. As he arrives, he catches Polydectes in the transgressive act of attempting to rape Danae and murder Dictys (his brother!). In a twist of irony, Perseus punishes the unfit king by holding forth the object of his quest, the head of Medusa. Polydectes is petrified when he gazes upon the head of the Gorgon, receiving a just reward for an unjust king. Yet again, the myth reinforces cultural values of proper and improper action.

5th century BCE silver roundel. MET 1995.539.3b.

Bellerophon and Pegasos do battle with an opponent wearing a Phrygian cap. This could be one of Iobates' ambushers or possibly an Amazon warrior that the hero overcame according to Homer.

Boston MFA must have some kind of unofficial monopoly on Bellerophon and Perseus vase paintings. eesh! Check out these two representations of Bellerophon:

Apulian stamos by Ariadne Painter (c. 400-390 BCE) (Bellerophon scene is on Side B). To my knowledge, this is the only surviving depiction of Bellerophon dealing with Proitos and Anteia/Stheneboia.

Orientalizing Protocorinthian aryballos (c. 650 BCE). Bellerophon vs. Chimera. One of the earlier surviving depictions of mythological narrative vase painting.

Bellerophon’s adventures occur chronologically close to Perseus’. Bellerophon, according to Apollodorus, had sought refuge in the home of “Proitos and [Bellerophon] was purified after accidentally killing his brother.” Thus, Bellerophon avoided the wrath of the Furies by seeking purification as a suppliant in a foreign land. This is the same Proitos who was brother to Acrisios, king of Argos (sometimes Mycenae) and grandfather of Perseus. Proitos is usually said to have ruled at Tiryns, a vassal kingdom to Mycenae.

There is a lot of similarity between the two heroes. They are both famous for slaying a monstrous mythological figure that did harm to humans: for Perseus it was Medusa, and for Bellerophon it was the Chimera. They are also both victims of deceit by the kings of their respective countries, and they are both roped into accomplishing “impossible” tasks that are designed from the outset to kill them. These are, in fact, common plot devices in most hero tales in Greek mythology.

The earliest extant story surrounding Bellerophon is found in Book 6 of the Iliad. Bellerophon is the grandfather of a Lycian prince, Glaucus, who has been asked to explain who he is to an opponent. In explaining his origin, Glaucus extols the exploits of his famous grandfather, Bellerophon:

Lakonian black-figure kylix attributed to Boreads Painter (c. 575-550 BCE).

Bellerophon and his steed, the winged horse Pegasus, battle the Chimaera. The monster has the head and body of a lion, a goat's head rising from the center of its back, and a serpent for a tail. The hero drives a spear into its breast and Pegasus pummels its neck with his hooves.

Bellerophon was Glaucus’ grandfather, according to the Iliad.

Although Homer refers to Bellerophron as having “divine blood,” he lists his father as Glaucus (as does Apollodorus). A fragment from a lost work by Hesiod, however, lists Bellerophon’s father as Poseidon. In any case, no direct mention is made of Pegesos in the Homeric account. Homer does cryptically allude to an “immortal escort” as Bellerophon traveled from Argos to Lycia. Many common themes can be derived from these various iterations of the Bellerophon myth:

First, like Odysseus and Perseus, Bellerophon is a virtuous man who respects the laws of civilization (bonds of marriage) and recognizes his place (subject to the kings, Proitos and Iobates respectively).

Second, Bellerophon is assigned “impossible” tasks with the unspoken intent that he would die trying to achieve them. That the hero prevails adds to his legend, of course, but it also vindicates him in the same way that Homer’s epithets of “blameless” and “faultless” signal to the audience that the hero is morally just.

Lastly, Homer and Apollodorus say little about Bellerophon’s fall, but Pindar does tell us something of the hero’s demise:

Homer does not mention the winged horse Pegasos, but Hesiod says that Bellerophon rode him when he killed the Chimaera. Pindar (Oly 13.64-69) tells of Bellerophon’s harnessing of Pegasos with the aid of Athena, and elsewhere he tells of Bellerophon’s attempt to fly up to heaven – the act that led to his fall. [12]

Bellerophon’s end affirms other constants in Greek myth:

[1] Literally “fames of humans” or “fames of men.”

[2] See inset below: Perseus Pursued by Gorgons.

[3] Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson, NY. 1991.

[4] We see this pattern throughout the klea theōn (fames of the gods) as well. In Hesiod’s Theogony, Ouranos performs the horrific act of burying his distasteful children back inside Gaia, symbolically pushing them back into the womb. His successor, Kronos, would later violate his position in the family by striking against and usurping his father’s place in the family, earning the designation titans, or “over-reachers” for himself and his siblings). Later, Kronos would prove himself to be an even more abhorrent father/king by committing an act of cannibalism and infanticide by eating his own children (the future Olympians) in a desperate bid to maintain his stranglehold of power over the cosmos. In violating these taboos, Ouranos and Kronos prove themselves to be both unworthy fathers and unjust rulers.

[5a] Gold signet ring. National Archaeological Museum, Greece. Dated 16th-15th century BCE. Inventory number P 6209.

[5] T. H. Carpenter. Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson (1991).

[6] Proitos was Acrisios’ twin brother and will be of greater relevance in the discussion of Bellerophon.

[7] T. H. Carpenter. Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames & Hudson (1991).

[8] Jason’ pursuit of the golden fleece, Herakles’ twelve labors, and the tasks assigned to Bellerophon are glaring examples in the Greek mythological corpus.

[9] Odyssey Book 5, lines 202-19. in The Essential Homer. Stanley Lombardo (trans.).

[10] Stheneboia was Proitos’ wife in Apollodorus.

[11] Iliad Book 6, lines 155-211. Essential Homer. Translation: Stanley Lombardo (2000).

[12] T. H. Lawrence. Art and Myth in Ancient Greece. Thames and Hudson (1991).