Book 16 is a pivotal point in the Iliad. Achilles’ anger toward Agamemnon and his resolve to remain out of the war are waning. Indeed, everything Athena promised him in Book 1 has occurred, but with the death of Patroclus, a more primal rage will drive Achilles and, thus, the narrative. Book 16 is not solely focused on Achilles, however. Both Sarpedon and Patroclus enjoy the heroic deaths that Priam will soon give voice to (Book 22), and the importance of burial in connection with memory are tethered to the deaths of these idealized Homeric heroes. } }Book 16 is a pivotal point in the Iliad. Achilles’ anger toward Agamemnon and his resolve to remain out of the war are waning. Indeed, everything Athena promised him in Book 1 has occurred, but with the death of Patroclus, a more primal rage will drive Achilles and, thus, the narrative. Book 16 is not solely focused on Achilles, however. Both Sarpedon and Patroclus enjoy the heroic deaths that Priam will soon give voice to (Book 22), and the importance of burial in connection with memory are tethered to the deaths of these idealized Homeric heroes.

Book 16 begins with a condensed version of the Embassy to Achilles from Book 9. Instead of three picked envoys sent by Agamemnon, however, the “embassy” consists only of Patroclus. The latter’s argument closely mirrors that of Ajax’s from Book 9 if his manner does not:

While they fought for this ship, Patroclus

Came to Achilles and stood by him weeping,

His face like a sheer rock where the goat trails end

and dark spring water washes down the stone.

Achilles pitied him…. (1-5)

The fact that Achilles feels pity in this encounter is in stark contrast to Book 9 wherein Ajax condemned Achilles as “pitiless.” Pity is deployed throughout the Iliad as a counteragent or antidote for rage because they engender opposite actions. Anger moves one to harm or do violence to another, while pity moves one to give aid to or succor another. By conspicuously noting Achilles’ pity for Patroclus, the poem signals a meaningful shift in Achilles’ attitude from Book 9.

Patroclus begins his plea to bring Achilles back into the fray by listing all the Greek warriors who have been wounded and driven from the battlefield. Then he shifts to Achilles’ own wound:

“The medics are working on them right now,

Stitching up their wounds. But you are incurable,

Achilles. God forbid I ever feel the spite

You nurse in your heart. you and your damned

Honor! What good will it do future generations

If you let us go down to this defeat

In cold blood? Peleus was never your father

Or Thetis your mother. No, the grey sea spat you out

Onto crags in the surf, with an icy scab for a soul.” (31-39)

In other words, the rest of the Greek heroes suffer physical ailments that can be treated, but Achilles’ problem is not physical. The anger or spite that he “nurses” in his heart is characterized as a poison and has driven him to disregard his own people or community. This is the same criticism Ajax leveled at Achilles in Book 9 when he accused the latter of being pitiless and savage. Ajax’s words, “Achilles has made his great heart savage” (9.647-8) and “The gods have replaced your heart with flint and malice” (9.658-9), are echoed by Patroclus:

“Peleus was never your father

Or Thetis your mother. No, the grey sea spat you out

Onto crags in the surf, with an icy scab for a soul.” (37-9)

In this metaphor, Achilles has no place in human civilization; he is not human. He lacks the familial relationships of a mother and father. Instead, he’s the product of violent and raw nature, spat out of the sea as it crashes into the rocky coast. Like Ajax before him, Patroclus laments the absence of pity in Achilles’ heart, an emotion for which there is no place while the hero “swells with rage.”

Yet we noted the presence of pity in Achilles during the opening lines of Book 16. That is significant, and it is reflected in Achilles’ reply to Patroclus, for he indicates that he will relent his anger and rejoin the army after all, but only after receiving the timē that was promised him in Book 9. Unfortunately, the army is in no position to honor that bargain. The ships are under attack, and the army fights for its very life. Thus, we are presented with one of the two rationales that the poem contrives to send Patroclus to the battlefield as Achilles’ proxy. Once the ships are safe, Achilles will formally rejoin the army, receive his promised honors from Agamemnon, and the Greek host will operate at full strength again. At any rate, that is Achilles’ plan. His instructions to Patroclus on this matter are telling:

Hit them hard, Patroclus, before they burn the ships

And leave us stranded here. But before you go,

Listen carefully to every word I say.

Win me my honor, my glory and my honor

From all the Greeks, and, as their restitution,

The girl Briseis, and many other gifts.

But once you’ve driven the Trojans from the ships,

You come back, no matter how much

Hera’s thundering husband lets you win.

Any success you have against the Trojans

Will be at the expense of my honor. (84-94)

In driving the Trojans away from the Greek ships, Patroclus will earn honor for Achilles, specifically the honors that were promised him in Book 9. For, as we noted above, in order to make good on those promises, Agamemnon needs to be alive and to command an army for which Achilles can fight. However, if Patroclus goes beyond simply preventing the Greek ships from being burned, it will be “at the expense of [Achilles’] honor.” In other words, Achilles would lose honor. The rationale is simple: any heroic feats Patroclus accomplishes, any Trojan heroes he kills, are feats and kills that Achilles cannot accomplish once he has returned to the army.

The problem with Achilles’ order is similar to the dilemma in which Hector will find himself outside the walls of Troy in Book 22: it requires the hero to act in a decidedly unheroic manner, to retreat. In Book 5, Diomedes held back because Athena ordered him to avoid conflict with the gods and because he saw that he would have faced off against a god, Ares. Achilles is mighty, but his order to Patroclus does not carry the weight of Athena’s to Achilles (Book 1) and Diomedes (Book 2) respectively. Nor does Patroclus have the ability to distinguish gods from men on the battlefield that Diomedes enjoyed earlier. Thus, the circumstances that allowed Diomedes to restrain his bloodlust and the unflinching pursuit of glory in Book 5 do not exist for Patroclus in Book 16. Nor is he in direct and conscious conversation with a god as both Achilles (Book 1) and Diomedes (Book 5) were.

Attic red-figure kalyx krater attributed to Euphronios (c. 515 BCE).

Twin winged gods Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) carry the corpse of the fallen Lycian hero Sarpedon from the battlefield. Hermes oversees the activity. The scene is framed by armed warriors on either side.

Photo: Sailko. (CC BY 3.0).

Armed with the god-forged armor of Achilles[1] and backed by the Myrmidons,[2] Patroclus sets forth wreaking havoc on the Trojans and their allies, sending them fleeing from the ships. It is during this retreat that Sarpedon turns to confront Patroclus:

Sarpedon saw his comrades running

With their tunics flapping loose around their waists

And being swatted down like flies by Patroclus.

He called out, appealing to their sense of shame:

“Why this sudden burst of speed, Lycian heroes?

Slow down a little, while I make the acquaintance

Of this nuisance of a Greek who seems by now

To have hamstrung half the Trojan army.” (455-62)

We last encountered Sarpedon in Book 12 where he played a crucial role in breaking through the Greek fortifications and delivered a speech that embodies the heroic ethos of both Greek and Trojan forces in the poem. In keeping with the Homeric ideal that Sarpedon represents, the Lycian lord shames his own men for running away from a fight, similar to the corrective actions we saw Hector take with Paris in Books 3 and 6. Sarpedon expresses a wish to ‘know’ Patroclus, to test his mettle in combat and gauge his skill as a warrior. Indeed, in the Iliad, to know a person’s quality is to meet him in combat. One’s warrior prowess functions as much as a test of one’s character as of one’s ability with spear, sword, and shield.[3]

But before Sarpedon can test Patroclus’ quality, the scene abruptly shifts to Olympos, and we find Zeus in the uncharacteristic role of a perturbed father whose child is on the cusp of death:

Zeus watched with pity as the two heroes closed

And said to his wife Hera, who is his sister too:

“Fate has it that Sarpedon, whom I love more

Than any man, is to be killed by Patroclus.

Shall I take him out of battle while he still lives

And set him down in the rich land of Lycia,

Or shall I let him die under Patroclus’ hands?” (469-75)

Zeus’ dilemma is thus: should he save his son in the way Aphrodite rescued Paris from certain death during his duel with Menelaus in Book 3? Or should he not intervene, allowing his mortal child to die in honorable combat, and thus secure the glory (kleos) for his bravery and sacrifice that Sarpedon championed in his own speech to Glaukos in Book 12?

In a sense, to save Sarpedon from death is to kill him, for it would destroy his reputation and strip him of the kleos that accompanies a heroic death. Allowing him to fight and die would secure for him a kind of immortality (kleos, fame, a place in the stories of his people). Recall that according to Sarpedon’s speech in Book 12, it is the very fact that mortals can die that gives their heroic activity meaning and grants them glory on the battlefield. Hera’s reply to Zeus is quick and tinged with incredulity:

“Son of Cronus, what a thing to say!

A mortal man, whose fate has long been fixed,

And you want to save him from rattling death?

Do it. But don’t expect all of us to approve.

Listen to me. If you send Sarpedon home alive,

You will have to expect other gods to do the same

And save their own sons – and there are many of them

In this war around Priam’s great city.

Think of the resentment you will create.

But if you love him and are filled with grief,

Let him fall in battle at Patroclus’ hands,

And when his soul and life have left him,

Send Sleep[4] and Death[5] to bear him away

to Lycia, where his people will give him burial

With mound and stone, as befits the dead.” The Father of Gods and Men agreed

Reluctantly, but shed drops of blood as rain

Upon the earth in honor of his own dear son

Whom Patroclus was about to kill

On Ilion’s rich soil, far from his native land. (477-94)

Hera is quick to point out that Sarpedon is mortal. He is fated to die as all mortals must. If Zeus were to rescue his son from death, then the other gods would feel entitled to do the same for their own children, and the natural order of the cosmos would be thrown out of balance. Fate, the ordering principle of the universe, would hold no sway, and that is key. What separates Zeus from his father, Kronos, is his dedication to cosmic justice embodied by Fate. Kronos sought to circumvent Fate by devouring his children, thus cementing his rule of the cosmos. Zeus, by contrast, works in communion with the Fates, ensuring an ordered and just cosmos. Here, we see that Zeus has the power to save his child from death, but he bears the obligation to allow Sarpedon to die. Failure to do so would turn the cosmic order on its head. As Hera suggests, it would open a floodgate from which mortals, literally “those who die,” would not die. But Zeus is not his not Kronos. He will not act out of self-interest against the order of the cosmos that he has so diligently championed. Sarpedon must die at the hands of Patroclus.

Indeed, Sarpedon would arguably prefer to die in combat rather than be whisked away as Paris was. Paris is viewed with disdain by the Trojan warriors and suffers constant beratement from Hector for his unheroic actions in the Iliad. Such actions and the shame that accompanies them are anathema to proud warriors such as Sarpedon, Glaucus, Hector, Ajax, and Achilles. Even Paris, whose cowardice is reviled by Greeks and Trojans alike, feels great shame for such actions, and that shame motivated him to act courageously.

In her reply to Zeus, Hera suggests that Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) carry Sarpedon’s corpse back to Lycia for burial, Zeus agrees, and the treatment of the dead becomes a more pressing concern in the Iliad.

Patroclus slays Sarpedon, and with his dying breath, Sarpedon expresses concern for his body: he exhorts Glaucus to fight for his corpse. Treatment of the dead is a critical element in the Iliad specifically and the Greek world generally. Funeral ceremonies and burial rituals are formulaic means by which society memorializes the deceased. Another term for the gravestone is a “memorial.” Proper treatment of the corpse (i.e., burial) is essential to the memory of a fallen warrior. The place of one’s burial is also important. It’s better to be buried in one’s homeland because it places the memorial closer to community and family members who are more likely to visit the site and remember the deceased. This is the great honor Zeus bestows on Sarpedon by having his child’s corpse borne safely to his homeland (Lycia); it will maximize the memory and, thus, the kleos that surrounds his son.

Sarpedon, of course, is unaware of Zeus’ plans for his corpse, but he is very mindful of the importance of preserving its integrity so that he will maximize society’s memory of him. With that in mind, he calls upon Glaucus to defend and retrieve his corpse so that his name will enjoy the honors heaped upon it in burial services and monuments:

“Glaucus, it’s time to show what you’re made of

And be the warrior you’ve always been,

Heart set on evil war – if you’re fast enough.

Hurry, rally our best to fight for my bod,

All the Lycian leaders. Shame on you,

Glaucus, until your dying day, if the Greeks

Strip my body bare beside their ships.

Be strong and keep the others going.” (527-34)

The threat of disfigurement of the corpse underlies Sarpedon’s anxiety over the treatment of his body. At this point, he mentions only the humiliation of being stripped of his armor at the Greek ships. However, if his body is possessed by the Greeks, then it remains unmourned and unburied by the Lycians and Trojans. He does not suggest that the Greeks will actively disfigure his corpse, but the humiliation entailed in its capture is still a blow to his kleos (memory in heroic tales, fame). Thus, he calls upon Glaucus with the threat of shame should the Greeks gain possession of his corpse. As we have seen in numerous instances throughout the poem, shame is a motivating factor, encouraging warriors to act honorably (in pursuit of honor and avoidance of shame).

In turn, Glaucus calls upon Hector to rally the Trojans in the battle for Sarpedon’s corpse:

“Hector, you have abandoned your allies.

We have been putting our lives on the line for you

Far from our homes and loved ones,

And you don’t car enough to lend us aid.

Sarpedon is down, our great warlord,

Whose word in Lycia was Lycia’s law,

Killed by Patroclus under Ares’ prodding.

Show some pride and fight for his body,

Or the Myrmidons will strip off the armor

And defile his corpse, in recompense

For all the Greeks we have killed by the ships.” (570-80)

Glaucus’ speech can be viewed as a tempered mirror of Sarpedon’s from a few lines earlier. It prods Hector to act honorably or incur shame, and it emphasizes the value of one’s armor as a form of timē, a trophy to be seized from the corpse by the victor. Glaucus directly addresses the possibility of disfigurement of the corpse for the first time. It has been a constant fear throughout the Iliad, evidenced by Aeneas risking his life in Book 5 to defend the corpse of Pandarus against Diomedes’ onslaught. And so a pitched battle erupts over the corpse of Sarpedon; the bodies of the living and dying make for a morbid burial mound dedicated to the dead hero whose actual body has been transported back to his homeland in Lycia in accordance with Zeus’ will:

Zeus turned to Apollo and said:

“Sun God, take our Sarpedon out of range.

Cleanse his wounds of all the clotted blood,

And wash him in the river far away

And anoint him with our holy chrism

And wrap the body in a deathless shroud

And give him over to be taken swiftly

By Sleep and Death to Lycia,

Where his people shall give him burial

With mound and stone, as befits the dead.” (700-8)

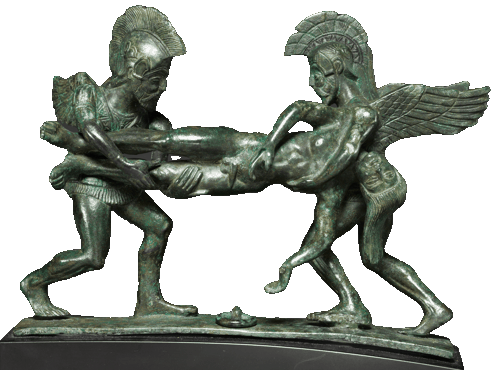

Bronze Etruscan Cista Handle (c. 400-375 BCE).

Cleveland Museum of Art 1945.13.

Handle to a bronze cista (a cylindrical lidded box). No figures are labeled, but the status of the twin winged warriors is secure. The corpse that they carry is almost certainly Sarpedon from events described in Book 16 of the Iliad, but there is speculation that it could also be Memnon, another demi-god ally of the Trojans whom Achilles slew during the war in events that occurred after the Iliad.

Patroclus’ victory over Sarpedon is his greatest martial achievement. Sarpedon was second only to Hector amongst the Trojans and their allies, and he was a mortal son of mighty Zeus. However, Patroclus’ aristeia is not the same that we have witnessed in the case of Diomedes or Agamemnon. Patroclus will not return to the ships to revel in his victory. We turn now to the death of Patroclus, the event that rekindles the rage of Achilles, dooming Hector and, presumably, Troy itself.

The gods manipulate mortals in many ways. We have seen them do so via dreams, prophecies, direct conversation, in disguise as familiar acquaintances, imbuing them with supernatural powers, and physically restraining them. Yet perhaps the most common way the gods manipulate mortals is by stoking their emotions. The Iliad is, after all, the story of the devastating effects of one such emotion, and we have witnessed the effects of rage on multiple figures in the poem. So too does Apollo manipulate Patroclus via emotion. After slaying Sarpedon,

Patroclus called to his horses and charioteer

And pressed on after the Trojans and Lycians,

Forgetting everything Achilles had said

And mindless of the black fates gathering above.

Even then you might have escaped them,

Patroclus, but Zeus’ mind is stronger than men’s,

And Zeus now put fury in your heart. (717-23 emphasis added)

This “fury” overwhelms reason, making Patroclus “mindless,” and like Achilles and Agamemnon before him, Patroclus takes action that he knows he should not, disobeying Achilles’ orders. The poem affirms this in Apollo’s cautionary words to the mortal warrior:

“Get back, Patroclus, back where you belong.

Troy is fated to fall, but not to you,

Nor even to Achilles, a better man by far.” (740-2)

The poem affirms the impropriety of Patroclus’ action by having him ignore the direct command of a god. Patroclus is, of course, fated to die during this encounter. So in a sense, he has no choice or free will in the matter. It is important to note, however, that the poem provides a rationale for his misfortune so that the cultural values of the poem are clearly affirmed. In other words, Patroclus is made culpable for his own death at the same time that his fate is clearly out of his control. This is not an unusual situation by any stretch. In fact, this episode is one of many that affirms the tragic world view of Homeric poetry.

Attic red-figure kylix (c. 510 BCE) from Vulci by Oltos Painter. State Museum,

Berlin.

Photo: Egisto Sani. Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Battle

of Ajax, Aeneas, Diomedes and Hippasos for the dead body of Patroclus. The

struggle over control of Patroclus’ corpse is the subject of Book 17 of the Iliad.

Patroclus successfully kills Hector’s half-brother and charioteer, Cebriones, and after a pitched struggle against forces led by Hector, comes away with the corpse and strips the armor from the dead man’s body. This is the last battlefield victory for Patroclus, and it ties into the ethnocentrism of the poem. In this encounter, Patroclus is able to defeat Hector through the mediation of a struggle for Cebriones’ corpse. This struggle immediately precedes Patroclus’ death, ultimately at the hands of Hector, but even though Hector strikes the mortal blow to Patroclus, it is the Trojan who will come out “third at best.”

After stripping the armor from Cebriones’ corpse, Patroclus launches himself back into the fray:

Three times he charged into the Trojan ranks

With the raw power of Ares, yelling coldly,

and on each charge he killed nine men.

But when you made your fourth, demonic charge,

Then –did you feel it, Patroclus? – out of the mist,

Your death coming to meet you. It was

Apollo, whom you did not see in the thick of the battle,

Standing behind you, and the flat of his hand

Found the space between your shoulder blades.

The sky’s blue disk went spinning in your eyes

As Achilles’ helmet rang beneath the horses’ hooves

And rolled in the dust

[….]

and Zeus would now give the helmet

To Hector, whose own death was not far off.

Nothing was left of Patroclus’ heavy battle spear

But splintered wood, his tasseled shield and baldric

Fell to the ground, and Apollo, Prince of the Sky,

Split loose his breastplate. And he stood there, naked,

Astounded, his silvery limbs floating away,

Until one of the Trojans slipped up behind him

And put his spear through, a boy named Euphorbus,

[….]

It was this boy who took his chance at you,

Patroclus, but instead of finishing you off,

He pulled his spear out and ran back where he belonged,

Unwilling to face even an unarmed Patroclus,

Who staggered back toward his comrades, still alive,

but overcome by the god’s stroke, and the spear.

Fresh off his successful confiscation of Cebriones’ armor, we find Patroclus at the height of his powers, infused with fury that is both a blessing and a curse. Killing nine men in every charge certainly rivals the prowess of Diomedes in Book 5. The text refers to these charges as “demonic.” That’s an unfortunate translation as it carries a different connotation in English than Greek. They might more accurately be referred to as a “god-influenced” or “divinely ordained” charges.[6]

Apollo strikes Patroclus between the shoulder blades, knocking his armor off and knocking Patroclus senseless. Only after the Greek hero is so dazed and disarmed does a relatively insignificant Trojan boy, Euphorbus, take the opportunity to spear Patroclus from behind. Then Hector moves in for the killing blow against Patroclus, now twice disabled. With his dying breath, Patroclus prophesizes the Greek’s ultimate victory despite his death at Hector’s hands:

“Brag while you can, Hector. Zeus and Apollo

Have given you an easy victory this time.

If they hadn’t knocked off my armor,

I could have made mincemeat of twenty like you.

It was Fate, and Leto’s son, who killed me.

Of men, Euphorbus. You came in third at best.” (885-90)

In other words, Hector did not prove his superior prowess by killing Patroclus. The Greek hero was disabled by Apollo and then Euphorbus. Hector might as well have killed a sickly, tethered bear. Even in defeat, then, Patroclus proves himself the greater warrior, and the poem nurses this point of view, because Patroclus is a Greek, and the Iliad is composed by and for Greeks. This is one of the more obvious moments of the poem in which its cultural bias (ethnocentrism) shines.

Book 16 sees the deaths of two great warriors, one a Trojan ally (Sarpedon) and one Greek (Patroclus). Both heroes die courageously and will, eventually, enjoy the honors of burial and a place in the stories of their peoples (kleos). They achieved, in other words, a heroic or beautiful death. If the poem seemed to meander in the first 16 books, the remainder of the epic narrows its focus to Achilles and his rage in the wake of Patroclus’ death. It is to that which we turn in the next essay.

[1] Achilles’ armor was passed down to him from his father, Peleus. Hephaistos, the smith of the gods, forged it as a gift to Peleus upon his wedding to the nymph Thetis. Hephaistos was particularly fond of Thetis because she served as a surrogate mother to him after he was cast out of Olympos as an infant by Hera.

[2] The Myrmidons are the warriors from Phthia whom Achilles commands.

[3] In Book 22, Hector will know Achilles in this way.

[4] Hypnos.

[5] Thanatos.

[6] Etymology is fun! The word “demon” is Greek but comes into English through Latin. The original word is daimōn, meaning supernatural spirit. So a daimonic charge is an attack influenced by supernatural forces. In Latin, the Greek dipthong ai is spelled ae, hence the Latin version of daimōn is daemon. As is often the case when adopting Latin words, the English version drops the a in the dipthong ae, resulting in the word “demon.” Over the course of time, particularly in monotheistic Europe, such pagan supernatural spirits were associated with devilry and evil. Thus we arrive, in broad strokes, at the modern meaning of the word demon and how it is related to, but significantly different from, the Greek daimōn.