Book 11 is often referred to as Agamemnon’s aristeia. We witness the leader of the Greek armies fight in the heat of battle, and he proves himself a very capable warrior. This performance serves to counterbalance the characterizations of the Agamemnon made earlier by Achilles (Book 1) and Thersites (Book 2). We also see in Book 11 Zeus’ plan to systematically remove Greek heroes from the battlefield, thus honoring his pledge to turn the tide of the war in favor of Hector and the Trojans so long as Achilles remains away from the battlefield, encased and isolated in his rage.

The book begins with a description of the burgeoning dawn and a description of daimonic (supernatural) manipulation of human action. First, the Dawn:

Dawn left her splendid Tithonos in bed

And rose to bring light to immortals and men,

As Zeus launched Eris, the goddess Strife,

Down to the Greek ships, a talisman of War

Clutched in her hands. (1-5)

The goddess of Dawn is Eos, and she is the personification of “Dawn.” Likewise, Eris is the Greek word for “Strife.” [1] Eos rises every morning, greeting the morning sky with her “rosy fingers,” the red sky of a rising sun. Thus, Homer refers to Eos in a formulaic introduction to signal the start of the day at numerous points throughout the poem. Tithonos was a brother of Priam, the king of Troy during the Iliad. He was one in a line of famously attractive Trojan males that include Paris, Deiphobos, Anchises, and Ganymede. His beauty was such that Eos took him for her lover. Like all mortals, however, Tithonos was doomed to grow old and die, so Eos attempted to circumvent that human destiny by making him immortal. Unfortunately, she failed to make him ageless, so that while Tithonos did not die, he continued to grow old and feeble, eventually wishing for death as a release from the physical and psychological pains of decrepitude.[2]

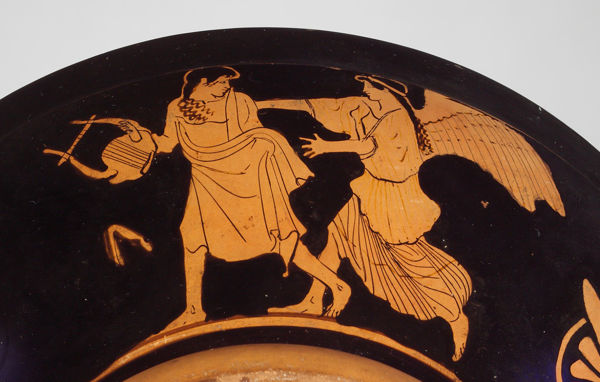

Detail from red-figure stemless kylix by the Penthesilea Painter (c. 460 BCE). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 96.18.76.

See discussion of Eos above.

Eris’ presence, meanwhile, is much like that of Dreams’ in Book 2. She works at the behest of Zeus to make manifest his plans for the Greeks and Trojans. Her purpose is to ignite hostilities so that the two armies might clash and the Trojans can push the Greeks back to their ships. Eris has a more storied history in this conflict, however. She was the being who set in motion the events that led to the Trojan War. She crafted a golden apple, inscribed “to the most beautiful,” and threw it at the feet of the gods who had come together for the wedding of Thetis and Peleus.[3] A dispute over the apple arose between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Paris eventually awarded the apple to Aphrodite in what was known as the Judgement of Paris, thus earning the wayward Trojan prince the favor of Aphrodite, goddess of love, but the eternal enmity of Hera, queen of the gods, and Athena, goddess of wisdom and helper of heroes (and one who never loses in battle!).

The day belongs to Strife:

They fought on equal terms,

Head to head, going after each other

Like rabid wolves. Eris looked on rejoicing,

The only god who took the field that day.

All of the others kept their peace,

Idle in their homes on Olympus’ ridges,

Sulking because the Dark Cloud, Zeus,

Meant to cover the Trojans with glory. (72-9)

In Homeric usage, Eris (Strife) appears interchangeably with Enyo (personification of War).[4] Thus, the strife attached to Eris in the Iliad is particular to the strife of war. Note that the combatants, both Greek and Trojan, are likened to “rabid wolves.” The imagery is distinctly savage, and Eris revels in their savagery. The Olympians take no part in Eris’ pleasure. In the larger world of Greek myth, civilization (law, reason) were bestowed on humans by Zeus. Dikē (Justice) and the Morai (Fates) are children of Zeus. Their concerns are human justice and human fate.[5]

The myths and folktales of many cultures include arming scenes. These scenes depict heroes dawning their gear for battle. The activity is practiced with ritual regularity and attention to detail. It may symbolize the hero’s transition from civilian to warrior. The idea of this arming scene is not entirely foreign to modern aesthetics. Sylvester Stalone’s Rambo character includes a ritual arming scene in each movie where the warrior clothes himself, ties his boots, applies face paint, and finishes by snapping his red bandana tightly around his head. The message is clear: the civilian has transformed into the soldier. The figure in the story has transformed into a warrior whose work is to kill, feeding the lust of Eris, Enyo, and Ares. Another example of this warrior’s ritual can be seen in the 2000 film Gladiator. The titular character, played by Russel Crowe, ritually rubs dirt between his hands as a process of transforming from a slave unwilling to fight to an unstoppable force in the gladiatorial ring or on the battlefield.[6]

The battle commences in the Iliad, and the two sides feel each other out. It is not until line 85 that there is a shift in the tide of war:

[Agamemnon] went on to kill Isus and Antiphus,

Two sons of Priam, bastard and legitimate,

Riding in one car. the bastard held the reins

And Antiphus stood by. Achilles once

Had bound these two with willow branches,

Surprising them as they watched their sheep

Now Agamemnon, Atreus’ wide-ruling son,

Hit Isus with his spear above the nipple

And Antiphus with his sword beside his ear

Knocking both from the car. As he was busy

Stripping their armor he recognized their faces

From the time when Achilles had brought them

Down from Ida and to the beachhead camp. (105-18)

The contrast between Achilles’ actions in the past the Agamemnon’s in the present is clear enough on the surface: Achilles once took the men prisoner and ransomed them away. Agamemnon simply kills them. However, Agamemnon does not recognize them until after he has slain them, so the comparison between past and present is difficult to draw conclusions from: “As he was busy stripping their armor he recognized their faces from the time when Achilles had brought them down from Ida and to the beachhead camp” (115-8). It does plant the seed, though, that something has changed from the way the war was waged previously to the way in which it is waged during the Iliad. The subtle suggestion, for which the botched ransom in Book 1 is evidence, is that the time for ransom and mediation through council, negotiation, and economic transaction has ended.

Agamemnon’s next encounter is more conclusive:

Peisander and Hippolochus were next,

Battle-hardened sons of Antimachus,

Who in the shrewdness of his heart

And in consideration of Pars’ substantial gifts

Had argued against surrendering Helen

To blond Menelaus. (129-34)

Peisander and Hippolochus were the sons of Antimachus, a Trojan lord. When Menelaus and Odysseus traveled to Troy as envoys to negotiate the lawful return of Helen before the war, Antimachus encouraged the Trojans to violate the laws of xenia and diplomacy by slaying the Greek kings who had entered the city under a banner of diplomacy. Furthermore, he did so at the urging of Paris, who bribed him. Although many Trojans are portrayed as victims caught in the web of Paris’ licentiousness and Priam’s affection for his son, the poem never lets its audience forget that the Trojans are culpable for the war. It was Paris who violated the bonds of xenia (hospitality) when he raped Helen from the home of Menelaus. It was Priam (or the assembly of Trojan lords in this excerpt) who harbored Paris despite his crime rather than return Helen and submit Paris for punishment. It was Pandarus, a Trojan, who broke the truce in Book 4.

Once again, Agamemnon is presented with the opportunity to ransom prisoners:

They fell to their knees in their chariot’s basket:

“Take us alive, son of Atreus, for ransom.

Antimachus’ palace is piled high with treasure,

Gold and bronze and wrought iron our father

Would give you past counting once he found out

We were alive and well among the Greek ships.’

Sweet words, and they salted them with tears.

But the voice they heard was anything but sweet:

“Your father Antimachus – if you really are

His sons – once urged the Trojan assembly

To kill Menelaus on the spot

When he came with Odysseus on an embassy.

Now you will pay for his heinous offense.”

He spoke, and knocked Peisander backward

Out of his chariot with a spear through his chest

And sent him sprawling on the ground.

Hippolochus leapt down. Agamemnon

Used his sword to slice off both arms

And lop off his head, sending his torso

Rolling like a stone column through the crowd.

He didn’t bother them further. (139-59)

Unlike the previous encounter, Agamemnon recognizes exactly who it is that asks him for mercy. Like Book 1, Agamemnon refuses to entertain the possibility of ransom, but unlike Book 1, Agamemnon’s refusal to take the Trojans prisoner does not violate any codes of civilized behavior in the Homeric world. What it does suggest, however, and in combination with Agamemnon’s prior encounter with Priam’s sons, is that the time for ransom has passed. The violence played out on the battlefield is becoming increasingly more savage, devoid of chivalrous combat, pity, and ransom. Arms and heads are cleft from bodies that are then left to roll across the blood-stained plain. The promise of horrific and savage death from the opening lines of Book 1 is becoming a reality.

Agamemnon’s aristeia continues for a few more encounters, but eventually he is wounded and forced to withdraw. This signals a shift in the tide of war, and Hector, as ordered by Iris, Zeus’ herald, leads a Trojan charge once Agamemnon vacates the battlefield. Both Odysseus and Diomedes are wounded and forced to withdraw as well. Nestor retreats with Eurypulus and Machaon in tow. The book ends with the Greeks in steady retreat behind the makeshift walls around their beached ships.

[1] She is better known today by her Latin counterpart, Discord. In English, discord and strife are particularly close synonyms.

[2] The tragic fate of Tithonos is used as a cautionary tale to reinforce the fundamental difference of mortality between gods and humans in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite. Eos and Tithonos produced a powerful son, Memnon, whom Achilles would slay during the war at some point after the events of the Iliad.

[3] Achilles’ mother and father.

[4] Enyo was the female counterpart to Ares.

[5] For the genealogy of Dikē and the Morai, see Hesiod’s Theogony.

[6] Minute marker 1:20 in the clip.