Book 8 is noteworthy for shifting the balance of power between Greeks and Trojans. Zeus made a pact with Thetis at the start of the Iliad that the Greeks would lose while Achilles sat out the war. Yet nothing of the sort occurred in Books 3-6. In fact, Book 3 included a duel between Menelaus and Paris wherein the Greek was clearly the better warrior than the Trojan. In Books 4 and 5, Pandarus, the master archer, failed twice to slay his Greek target and was finally killed by Diomedes. Book 5 showed a Greek route of the Trojans and two gods under the aristeia of Diomedes. Book 7, which our edition of the text skips, included a duel between Ajax and Hector, the best warriors of each army in Achilles’ absence, and that contest ended in a draw. Thus, up to Book 8, the best that can be said for Trojan martial prowess is that Hector fought Ajax to a draw, and both Aeneas and Paris survived despite being overmatched in battle. One could argue that Book 8 is the first meaningful plot movement regarding the rage of Achilles, since Dream tricked Agamemnon into renewing hostilities in Book 2.

At the beginning of the book, Zeus issues an order that no Olympian set foot on the plains of Troy or interfere with the war. He reinforces this order with the threat of violence:

If I catch any one of you with a private plan

To assist either the Greeks or Trojans,

He – or she – will return to Olympus

A crippled wreck – unless of course I hurl

Him – or her – into moldy Tartarus,

Down into the deepest underground abyss,

Iron-gated and bronze-stooped,

As far beneath hades as the sky is above earth. (12-19)

This image of Zeus is, in some ways, fitting for a poem soaked in blood, but in other ways, it is a jarring picture of the Olympian patriarch. This image of a Zeus who needs to coerce obedience from his wife and child with the threat of violence may appear in stark contrast to the Zeus who is the centerpiece of Hesiod’s Theogony, a slightly later Archaic epic that contrasts the narcissistic, unjust savagery of his predecessors with Zeus’ establishment of cosmic justice, order and the reciprocation of honor – a civilizing force. We shall see as the narrative progresses that Zeus does live up to these high-minded ideals, but it is also true that the Iliad paints a more disjointed picture of the Olympian household, one in which Zeus regularly needs to remind his siblings and children of his power over them.

Copyright: Uploaded by ArchaiOptix

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

Copyright: Uploaded by Sailko

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

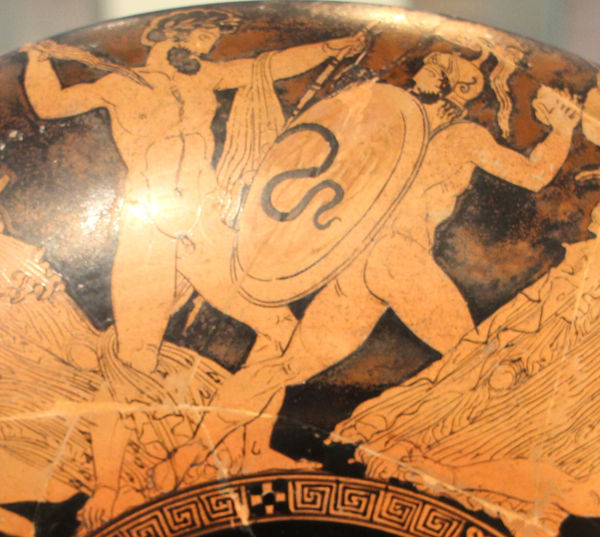

Attic red-figure kylix by the Aristophanes painter (c. 410 BCE)

Visual representations of the brothers Zeus and Poseidon are identical without their attributes. The images above are of the same kylix (drinking cup), depicting scenes from the Giantomachy (war between the Olympians and Giants). Poseidon (left) thrusts his signature trident at the giant, Polybbotes, while the giant’s mother, Gaia, rises up from the ground to plea for her son’s life – the word Giants, Gigantes, means “born from Gaia.” The scene is on the interior of the cup. Depictions of the battle wrap around the exterior of the cup as well. A detail is shown (right) of Zeus pressing down on the giant, Porphyrio, with his signature lightning bolt cocked in his right hand. The trident and thunderbolt, respectively, are the attributes that visually differentiate the two brothers.

In the Iliad, Poseidon complains that Zeus and he are, in fact, equals: they drew lots, and Zeus drew the sky while Poseidon drew the sea, and Hades drew the underworld, but the Earth was common to them all. Nevertheless, Poseidon is included among the Olympians and, in the Iliad, he gives way to Zeus’ command that he withdraw from the plains of Troy.

The fact that Zeus needs to constantly remind his siblings and children of his power is, in fact, deeply woven into the fabric of the poem. The reason Thetis thought she could sway Zeus to honor Achilles in Book 1 was the direct result of an earlier power struggle on Olympus. Achilles narrates the circumstances in Book 1:

Go to Olympus

And call in the debt that Zeus owes you.

I remember often hearing you tell

In my father’s house how you alone managed,

Of all the immortals, to save Zeus’ neck

When the other Olympians wanted to bind him –

Hera and Poseidon and Pallas Athena.

You came and loosened him from his chains,

And you lured to Olympus’ summit the giant

With a hundred hands whom the gods call

Briareus but men call Aegaeon, stronger

Even than his own father Ouronos, and he

Sat hulking in front of cloud-back Zeus,

Proud of his prowess, and scared all the gods

Who were trying to put the son of Cronus in chains.

Remind Zeus of this, sit holding his knees,[2]

See if he is willing to help the Trojans

Hem the Greeks in between the fleet and the sea. (1.409-26)

Thetis remained loyal to Zeus during this coup, presumably led by Hera. In the Iliad’s telling of it, Thetis both cut Zeus’ bindings and fetched one of the Hundred Handers[3] to protect Zeus and intimidate the other Olympians.

In Book 8, Zeus then went to work favoring the Trojans; He “thundered from [Mt.] Ida and sent a blazing flash into the Greek army. The soldiers gaped in wonder, and their blood turned milky with fear” (80-2). In a way, Zeus deals with the Greeks in a similar manner that he has just dealt with the Olympians; his strikes cause them to cower in awe and fear of his terrible might. There is one significant difference, however: with humans, this show of power is absolute. Hera and Athena, in the frustration of their desires and pity for the Greeks, scheme to disobey Zeus’ command that they not interfere.

Zeus notices his wife and “favorite daughter” (392) mounting a chariot to descend to the battlefield in defiance of his command. He dispatches Iris[4] to deliver a message that they will face off with him if they continue on their course. It is the end of his message that most interests us:

The grey-eyed one must learn what it means

To fight with her father. As for Hera,

I am not so angry with her, since she

Always opposes whatever I say.” (416-19)

The following relies heavily on sources outside the Iliad, largely Hesiod’s Theogony and the Homeric Hymns, but they are instructive in this regard. Olympus was not a place where souls of the dead resided or a reward any mortal could look forward to. It was not the innate center of the world or the cosmos – Delphi might make a stronger claim to that title. The significant of Olympus is that Zeus makes his home there. In fact, Olympus and the Olympians are the household of Zeus. He is the patriarch or kurios (male head of household). Olympus is populated with his siblings (some of them), his wife, and his divine children. They are all subject to his rule as any siblings, women, or children would be in a mortal household. In this regard, the end of the message Zeus dispatches with Iris makes sense: wives came from outside the family[5] and were often considered to have divided loyalties between the birth family and the family they married into. Athenian men were historically suspicious of their wives, a suspicion that is reflected in Agamemnon’s advice to Odysseus in the Odyssey. This tension is implicitly acknowledged by Zeus’ message in the Iliad.

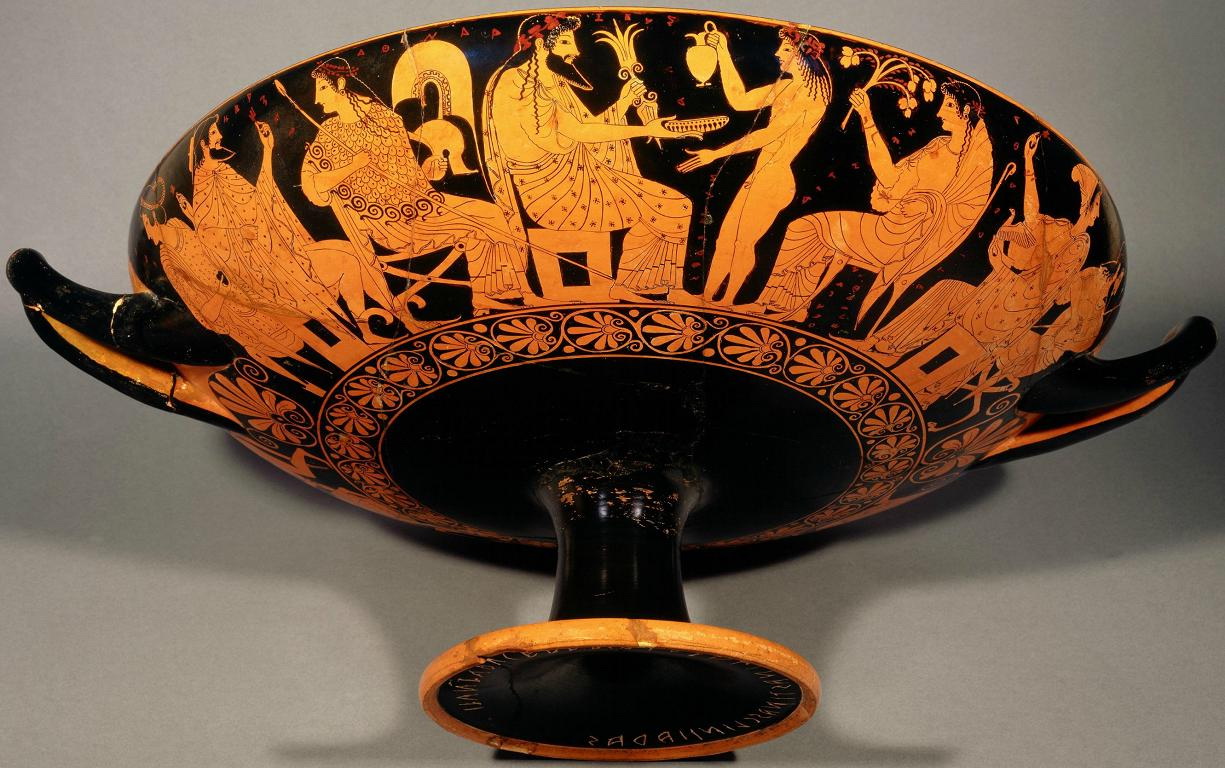

Red-figure kylix attributed to Oltos (c. 510 BCE).

Zeus sits enthroned at center. Ganymede replenishes his cup (phiale) while Hestia, goddess of hearth and home, or Hera, his wife, looks on. Athena seated behind Zeus converses with Hermes; Hebe(?) sits behind him. On the right, Aphrodite speaks with another figure behind her (Ares?).

Note the stylized lightning in Zeus’ left hand; the helmet, spear, and aegis on Athena; and the swan in Aphrodite’s hand. All are reliable attributes of the respective gods. Although Aphrodite is most commonly identified by the company of Eros (sometimes aspectual in miniature).

Image: Athena, Zeus, Ganymede, Hestia. Art History Reference August 8, 2019.

Athena is another matter entirely. If Hera is figuratively ‘from another house,’ then Athena is literally from Zeus; She was born from Zeus’ head. Athena is wholly “of Zeus” or belonging to Zeus. There can be no question about a maiden’s loyalties, an unmarried daughter living in the house of her father. In that situation, his rule is absolute, and the insult of her rebellion, as well as the father’s imperative to assert his authority, would be fiercely manifest – as they are in Zeus’ ire.

In the end, Zeus’ threats prove enough. Athena and Hera are cowed, and Hera announces as much: “We’re all too familiar with your irresistible strength, but we still feel pity for the Danaan spearmen who are now destined to die an ugly death” (475-77). This is the second time Hera uses the term “ugly death” in Book 8. The idea that the war was going to get “ugly” was stated in the opening lines of Book 1 in the description of Achilles’ rage, but we have seen little of this ugliness thus far, just honorable duels and chivalrous combat. Book 8 heralds a less aesthetically pleasing kind of warfare. As J. P. Vernant put it, “When battles become more heated, chivalrous combat – with its rules, its code, its prohibitions – is transformed into savage struggle, in which the bestiality that lurks in violence comes to the surface in all the participants.”

With that, Zeus makes his intentions known:

“Hector will not be absent from the war

Until Achilles has risen up from beside his ship

On the day when the fighting for Patroclus’ dead body

Reaches its fever pitch by the ships’ sterns.

That is divinely decreed.” (485-89)

The Iliad will soon become a theater of the horrific. Battles will rage over the corpses of fallen heroes. Opposing sides will sacrifice piles of their own dead just to mutilate or prevent the mutilation of a fallen warrior. Bonds of xenia will be acknowledged and then cast aside. There will be no more talk of prisoners or ransom. Pity will evaporate as suppliants are dispatched. Ugly death awaits Greek and Trojan alike as the promise of the opening lines of the poem are realized: incalculable pain as innumerable souls of heroes are sent to the underworld while their bodies rot horrifically as carrion for scavenging animals (e.g., go unburied).

[1] Barry B. Powell. Scenes from the Iliad in Ancient Art Figure 14.2. Oxford University Press Blog. December 14, 2013.

[2] Formal suppliant behavior.

[3] The Hundred Handers were enormous children of Ouronos & Gaia whom their father and, later, Kronos, either buried inside the Earth (Gaia) or trapped in Tartaros. Zeus freed them in exchange for their help in his war with the Titans, and he honored the Hundred Handers by making them guardians of the prison that now holds the Titans who persecuted them. They are deeply loyal to Zeus and their signature attribute, in addition to the hundred hands, is size & strength.

[4] Winged messenger goddess. She is associated with the rainbow, which typically connects the clouds to the earth as if it were a messenger from the heavens! Iris is more often employed in the service of Hera whereas Zeus would use Hermes, but that is clearly not a hard and fast rule. They are both messenger gods.

[5] Ironically not the case for Hera and Zeus, but Hera represents wives in this relationship.